As a young man living in Venezuela, Jose Garcia remembers being woken up in the middle of the night by his mother to watch tanks storm the Miraflores Palace in the capital of Caracas. It was 1992, and the Venezuelan military, led by Hugo Chavez, was attempting a coup d’edat against the democratically elected President Carlos Perez. In the end, the coup failed and Chavez was imprisoned.

Only four years later, Chavez himself was democratically elected president of the country, with roughly 60 percent of the population voting for him, including Garcia.

“The sentiment was that the system was basically serving itself,” Garcia says. “People revolted against the system and basically wanted another revolution. But revolutions don’t guarantee a better state.”

Garcia says he witnessed first hand the aggressiveness and corruption of previous governments, and therefore, like the majority of his country, wanted radical change.

“My father was shot and almost killed before Chavez came to power,” he says. Incorrectly assuming Garcia’s father, a cattle rancher in the Andean city of Merida, was driving a stolen vehicle with hopes to sell it in nearby Colombia, law enforcement “just came up, no questions asked, and shot him with a military rifle. So that was the kind of stuff that [Chavez] said they were going to change.”

Over the next decade, Chavez increasingly consolidated political power while nationalizing private industry, all in the name of his socialist revolution. At the same time, global oil prices surged to all time highs and with its oil-rich lands, money poured into Venezuela.

“Those were good years,” Garcia says. “There was plenty of money in the streets, people were eating. When you have such a landfall of money, it doesn’t matter if you’re running the economy into the ground.”

Now, just three years after Chavez’s death, Venezuela’s economy is in complete disarray as inflation has reached 720 percent in the last year and the International Monetary Fund estimates it could reach 1,600 percent in 2017. And President Nicolás Maduro, Chavez’s named successor, has faced increasing unrest as thousands of protesters gathered in the beginning of September demanding a recall referendum, hoping to oust the leader by the end of the year.

Although Garcia has lived in Nederland since 1996, the rest of his family still lives in Venezuela. Due to the growing unrest and violence as a result of the failing economy, Garcia hasn’t been back to visit in several years. However, his younger brother Marco Antonio Garcia Noguera is visiting the Boulder area while his exhibit The Faces of Little Luck is on display at the The Dairy Arts Center.

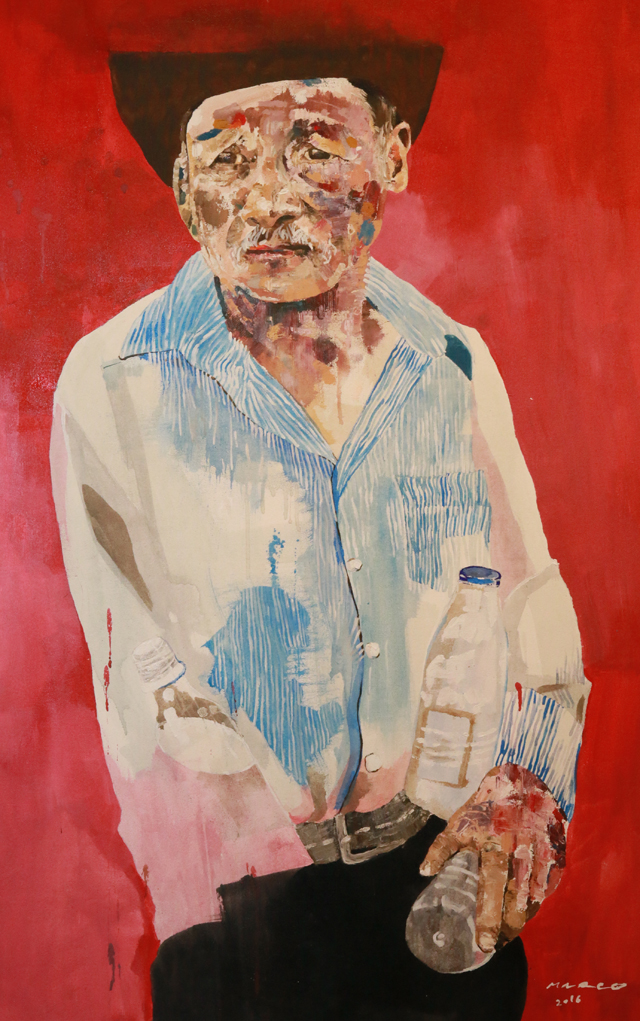

Based off a series of photographs documenting ordinary Venezuelans as they wait in line, sit in traffic or eat what little they have, Noguera’s paintings depict the emotional realities of present day life in the country.

“I feel the pain of the people who are hard working. They are trying but they are barely surviving,” Noguera says. “I feel that we pulled the lucky straw because we have what we have. Why is it that we live well? That we are one of the few?”

For Noguera, his father’s cattle ranch provides enough for the family to buy goods at highly inflated black market prices, but he doesn’t know how the majority of the population survives. Official exchange rates still estimate 9.98 bolívars to the dollar, but Noguera says the black market has reached 1,000 bolívars to the dollar. The Washington Post has reported the value of the Venezuelan currency has decreased by 99 percent in the last three years alone while it is estimated that three out of every four Venezuelans live below the poverty line.

“The economy is decaying exponentially fast in respect to the moment Chavez died,” Noguera says. “The decay is exponential. In the last three years our entire way of life has disappeared.”

He consistently sees people digging in the trash, desperate to find food, he says. As a result of hyperinflation, roughly 80 percent of the population has to stand in line for the basic fundamentals such as corn flour and powdered milk, as well as household items such as toilet paper and deodorant.

“On Fridays they start getting organized because the material will start arriving 48 hours later,” Noguera says. “Your position in line is highly valuable, in fact it’s a commodity that you can trade … And the final result of this is two bags of 2 kilos of corn flour after 48 hours in line. From my point of view, I have no idea how people live.”

NPR, the New York Times and others report that most Venezuelans exist on less than three meals per day. Noguera says, he’s visibly noticed many of his friends lose weight. And although his girlfriend, who has epilepsy, survives off of medicine sent by relatives living in the U.S, most Venezuelans aren’t as fortunate.

In addition to food lines and rolling blackouts, the economic crisis has resulted in a public health nightmare, as infant mortality rates surge and people succumb to treatable conditions due to a lack of supplies in hospital. Antibiotics, cancer medicines and other prescriptions are almost impossible to come by, save for the black market. The New York Times has also reported that surgeons lack necessities, such as soap, water and electricity, often leaving them little choice but to operate on soiled gurneys, while malaria cases have increased 72 percent in 2016 alone.

Garcia adds that in 2014 his uncle died in agony of cancer in the hallway of a hospital, on a bed still half covered in blood.

Noguera says everyone has stories of minor thefts and muggings as well. He’s been chased by people he assumes were trying to steal from him, and at one point a man was pulling a gun out of his waistband as Noguera ran the other way.

“My mom, just before I came, we were buying vegetables in the market and when we came back to the car everything was taken,” Noguera says. “A week later, she was driving and stopped, waiting for the light to change and a guy knocked on the window and robbed her.”

“In Venezuela we say, ‘It’s not if, it’s only when,’” Garcia adds.

Although the government statistics are much lower, an independent NGO, the Venezuelan Violence Observatory, reports there were 90 homicides per 100,000 citizens in 2015, and TIME cites another report that estimates the murder rate could be as high as 119 per 100,000. In comparison, there are 4 homicides for every 100,000 in the U.S. each year.

Even Garcia and Noguera’s father, despite having enough resources to provide the fundamentals for his entire family, faces security issues, as the crime and murder rates in the country have dramatically increased. Their father also faces increased harassment from law enforcement while delivering meat and cheese from his ranch to local markets. “Now my father gets arrested every other day because he’s a very strong man and he’s tired of being abused,” Garcia says. “He gets arrested or detained because he refuses to pay the bribe or yield his goods.”

And as a school teacher, Garcia’s mother has been severely affected by inflation.

“Right now she doesn’t even have money to eat,” Garcia says. “Imagine you work your whole life in the Boulder Valley School District, you are earning $2,000 a month. Ten years later you are earning $10 a month because of inflation. No one makes enough money to live.”

Garcia says the older generation, like his parents, are too rooted in the country to ever consider leaving, no matter how difficult it gets. And his generation is holding out hope for things to change.

“It reminds me of a famous thing that happens in Venezuela which is when the rivers flood and the fish live wherever. But when the scarcity comes, when the summer comes, they make ponds and you live a while but as the summer progresses the ponds get smaller and smaller and smaller,” he says.

“And in the end they start asphyxiating, which is happening now. The pond becomes like acid, the oxygen levels drop and you know who survives in those ponds? The piranhas. … At the end of the day only the piranhas survive. Many of my family are holding to that hope that the rains will come back, the ponds will expand.”

As for the younger generation, Garcia says, they are doing anything they can to leave. If they have the resources to do so.

Noguera has been studying civil engineering at the University of the Andes in Merida for four years. He expects it will take him three to four more years to complete his bachelor’s degree.

“The teachers get paid about $30 a month and there is unrest almost every 15 minutes, and so a semester turns into a year, a year into… Every two minutes there is a strike, there’s another unrest, they are burning tires again.”

Despite the time investment, Noguera says he doesn’t expect to earn a living in the engineering field after finishing his degree.

“There are teachers, with Ph.Ds, 30 years to be tenured professors and they are making, say, $50 a month. What can I expect [to make] with a bachelor’s in civil engineering?” he says. “In the short term I want to finish my education. And then if the economic and political situation doesn’t change, I will try to live any other place.”

As the economic crisis continues and efforts to create political change fail, Noguera has noticed classmates become increasingly submissive. Although thousands of students protested after Maduro was narrowly reelected in the spring of 2013, hundreds were arrested and detained as “traitors to the homeland,” while there have also been reports of torture.

“The college students know that there is no hope that the people can actually change things because traditionally in Venezuela, the military takes control,” Noguera says.

If nothing changes at home, if Maduro doesn’t allow for a referendum and the military doesn’t give up political control of the country, “Everyone who can leave, will leave,” he says. “It will be the biggest exodus from Venezuela.”

From Garcia’s point of view, Venezuela is essentially in an undeclared state of war as the general population lacks basic essentials such as food and medicine while facing increasing violence. At the same time President Maduro and the ruling elites increasingly deny the dire realities of everyday life.

“You see the same thing all over the world,” he says. “These strong oligarchs don’t get that everyone else needs to make a living.”

In fact, he sees similarities between Venezuela and the growing critique of the U.S. political system as seen in the 2016 presidential race. In many ways, the rise of political figures like Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump reminds Garcia of the rise of Chavez, despite the glaring ideological differences in political thought. Chavez was able to gain widespread support by tapping into Venezuelans’ anger and disillusionment with the power establishment, but in the end this has left the country in further disarray.

“I think we have to understand that Venezuela took a necessary step towards overthrowing an establishment that was only self-serving, but in the process of revolutions you don’t guarantee a better outcome,” he says. “People have to be aware of the strongman with big promises.”

At the same time, Garcia warns against disparaging Trump-supporters, calling them “stupid” and “idiots,” because it will only further alienate them. “I know the majority of the people who will vote for Trump, they are good people and they are just desperate,” he says. “There is no us and them. There is only we.”

As for Venezuela, both Garcia, and his brother Noguera through his art, hope to share what’s happening in their home country with a broader audience, not necessarily asking for help, but as a way of self-examination.

“At the end of the day, it’s not about the responsibility of our (Boulder) county, our (Colorado) state, our country (the U.S.) to solve Venezuela’s problems,” Garcia concludes. “But at least we should be aware that for our own nation, we are headed down a similar path, in my opinion. The path of inequality breeds resentment, resentment brings radicalism and there goes the baby with the bathwater. That’s what worries me.”