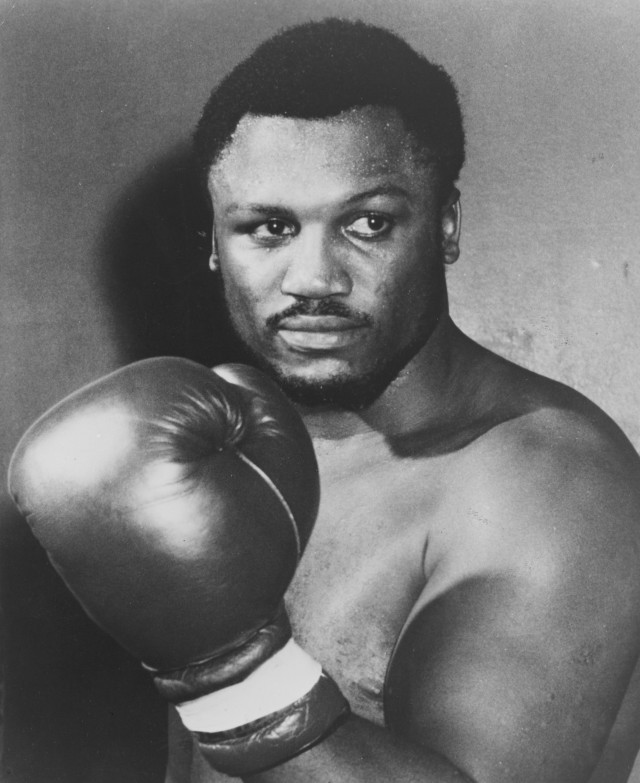

PHILADELPHIA — Joe Frazier, the son of a South

Carolina sharecropper who punched meat in a Philadelphia slaughterhouse

before Rocky, won Olympic gold, and beat an undefeated Muhammad Ali to

become one of the all-time heavyweight greats, died on Monday, his

family said in a statement. He was 67.

Frazier,

whose liver cancer was diagnosed about a month ago, spent his last days

living under hospice care in a Center City apartment.

Frazier,

known as “Smokin’ Joe,” was small for a heavyweight, just under 6 feet

tall, but compensated with a relentless attack in the ring, bobbing and

weaving as if his upper body were on a tightly coiled spring, constantly

moving forward, and throwing more punches than most heavyweights.

“A

kind of motorized Marciano” is how Time magazine described his style in

a 1971 cover story before Frazier’s $5 million fight with Muhammad Ali,

the first of their three epic battles and the most lucrative boxing

match ever at the time.

Fans could watch Frazier fight for minutes at a time and not see him take one step back.

“There

were fights when he didn’t step backward. He took very few backward

steps in his career,” recalled Larry Merchant, the HBO boxing analyst,

who was a Philadelphia newspaperman during Frazier’s early years. “What

made him good was not so much his punching power as his willingness to

keep coming and walking through the fire, his toughness and grit — and

willingness to train so he could take the kind of punishment a fighter

take in order to get to his opponent.”

Frazier’s

signature weapon was a destructive left hook, which he used to win his

first title in 1968 and floor Ali in their first meeting in 1971. He

developed his powerful left as a young child, growing up without

electricity or plumbing in rural Beaufort, S.C. His father had lost his

left arm in a shooting over a mistress, and young Joe became his

father’s left arm.

“When I was a boy, I used to

pull a big cross saw with my dad. He’d use his right hand, so I’d have

to use my left,” Frazier once said. After watching boxing on TV with his

father, he filled a burlap sack with a brick, rags, corncobs, and moss,

then hung it from a tree.

“For the next six,

seven years damn near every day I’d hit that heavy bag for an hour at a

time,” he wrote in his 1996 autobiography.

At age

15, Frazier moved north to New York and then Philadelphia, where he

found work at Cross Bros. Meat Packing Co. in Kensington. He began

training in a Police Athletic League gym, won three national Golden

Gloves titles, and then a gold medal at the 1964 Olympics in Tokyo.

WARS WITH ALI

Frazier

won the world heavyweight title in a series of elimination bouts from

1968 to 1970 while Ali was banned from boxing, but the accomplishment

wasn’t complete. Ali had been stripped of his title in 1967 for refusing

induction into the U.S. Army during the Vietnam War and remained the

true champion to many fans during his exile from boxing.

Frazier

was labeled the “official” champion. He lobbied privately for Ali’s

return to boxing and even loaned him money. But as a match between the

two became inevitable, he found himself in a mean-spirited psychological

battle with the media-savvy Ali, who goaded him, calling him an “Uncle

Tom” and a “gorilla.” Frazier, who preferred to speak through his

actions, called Ali a draft dodger and referred to him by his original

name, Cassius Clay.

The two came to represent the wider rifts in the nation during a turbulent era.

“Joe

was a champion — and Ali was a hero,” Merchant recalled. “Joe was an

ordinary guy, and Ali was an exceptional guy. … People lined up on

both sides.”

Frazier’s 1971 win over Ali at Madison Square Garden was his crowning achievement.

“He

said if I whipped him that night, he would get on his knees, crawl

across the ring, and say: ‘You are the greatest,’ “ Frazier said. “But

he didn’t do that. I think he was trying to get to the hospital.”

He

lost his world title in 1973 to George Foreman and never won it back.

He lost twice after that to Ali, the last in the brutal “Thrilla in

Manila” in 1975. Frazier ended his career with 32 wins, 27 by knockout,

four losses, and one draw.

No ‘little-boy life’

Frazier

was born on Jan. 12, 1944, one of 13 children of Rubin and Molly

Frazier. In a 1974 interview with The Inquirer he said: “One day I was

talking to a reporter, and it dawned on me I didn’t know what number I

was, 13 or 12, so I got on the phone with my momma and asked her. I

think I’m number 12. Thirteen, he died.”

Rubin

Frazier was a sharecropper in the segregated South who made money on the

side as a bootlegger. Joe was put to work chopping wood, picking

cotton, and holding tools for his father as a 7-year-old, often starting

his days at 4 a.m. “I never had a little-boy life,” he would say.

He

had put boxing aside by the time he arrived in Philadelphia. Feeling

overweight, he entered the PAL gym at 22d Street and Columbia Avenue and

began drawing attention as a boxer. Under trainer Yancey “Yank” Durham,

a former sparring partner to Joe Louis, Frazier won 37 of 40 amateur

fights by knockout.

“Go out there and make smoke come from those gloves,” Durham used to say, inspiring the nickname “Smokin’ Joe.”

Frazier

lost to Buster Mathis in the 1964 Olympic trials, but when Mathis

injured a knuckle, Frazier took his place on the team. He won his first

three bouts in Tokyo by knockout, breaking his thumb in the semifinal.

Inspired at how his father had managed without a left arm, Frazier

outpointed Germany’s Hans Huber with a painful broken thumb to win the

gold medal.

SYNDICATION

Frazier

had married Florence Smith in Beaufort when he was 17 and she was 15.

The family, with three young children, struggled when he returned from

the Olympics to Philadelphia.

A newspaper story

explaining their plight prompted civic leaders to give the family money

and toys for Christmas, and that eventually led to an unusual business

arrangement.

The Rev. William H. Gray of Bright

Hope Baptist Church, who had given Frazier odd jobs at the church,

introduced the boxer to F. Bruce Baldwin, president of Abbotts Dairies.

Baldwin assembled a group of local leaders to invest in Frazier. The

company, called Cloverlay, sold 80 shares at $250 apiece. Frazier would

receive $100 a week as a draw against his boxing earnings, which would

be 50 percent of his purses; his training expenses would be paid from

Cloverlay’s cut.

Frazier told The Inquirer in 1966

that he consulted with his wife and decided to sign the deal “because

we think it is a swell thing.”

The syndicate

bought a three-story building on North Broad Street, a former bowling

alley and ballroom, and made it Frazier’s gym.

“I

don’t think most people at the beginning thought that Joe was

championship material necessarily, but they did know he was a

crowd-pleasing fighter,” said boxing analyst Merchant, who said he

bought one share for something to write about.

“It

was like buying shares in Microsoft. … I paid $250 and sold for about

$2,000,” he said. Due to stock splits, an original $250 investment

eventually would be worth more than $14,000. Cloverlay grew to nearly

1,000 shareholders.

‘FIGHT OF THE CENTURY’

Frazier

had his first tough professional test against Oscar Bonavena in 1966.

Frazier was 11-0 with 11 knockouts, but the tough Argentine knocked him

down twice in Round 2. But Frazier survived and won a split decision. In

1967, he knocked out Tony Doyle in the first boxing event at the

Spectrum in Philadelphia.

After Ali was suspended

from the sport, Frazier fought Mathis in 1968 for what the New York

State Athletic Commission called the world heavyweight championship.

Mathis — in the first boxing event at the new Madison Square Garden —

poked and danced to win first the half of the fight, as he’d outpointed

Frazier when they were amateurs. But Frazier was unrelenting. In Round

11 he floored Mathis with a left hook, and the referee stopped the

fight. Five fights later, in 1970, Frazier stopped Jimmy Ellis to become

official world heavyweight champion.

But Ali loomed.

“He

got in more than my head. He got in my mind, my heart, my body,”

Frazier said of Ali in a documentary. “I’d go to bed at night, and I

could see him — and we’d fight. … I used to wake up the next morning,

wet with sweat.”

That first Ali-Frazier bout was

like worlds colliding. Never before had two undefeated heavyweight

champions met. An estimated 300 million people worldwide watched. Ali

dominated early rounds, but Frazier wobbled him with a hard left hook in

Round 11 and knocked him down with one in Round 15, winning a unanimous

decision.

Their rematch was less eventful, but in

their third meeting, in Manila, neither man gave ground. They beat each

other devastatingly. Frazier lost when he could not answer the bell for

Round 15, but it was Ali who spent the night in the hospital.

Frazier

for decades resented the way the public embraced Ali and held a grudge

for decades over how Ali vilified him in the run-up to their first

fight.

At the 30th anniversary of their first

fight, with Ali’s health fading, the men hugged and made up. In a 2006

interview with The Inquirer, Frazier said: “I forgive him, and it’s up

to the Lord now to do the rest of it. If I’ve done something wrong to

you or said something wrong, I’m sorry. I hope he accepts that.”

THE LATER ROUNDS

Frazier

had 11 children by at least four women. With Florence, he had daughters

Jacqueline, Weatta, Jo-Netta, and Natasha, as well as his oldest, son

Marvis, who went 19-2 fighting as a heavyweight. Marvis is a preacher

who helped run the Frazier gym. Frazier and Florence divorced in 1985.

Frazier

had daughter Renae and son Hector with another woman during his

marriage. His other children are Joseph Rubin, Joseph Jordan, Brandon,

and Derek.

After his boxing career, Frazier kept

busy making guest appearances but was unable to capitalize on his name

the way Ali and Foreman did. He took over the Frazier gym and became a

coach and mentor to young boxers. Speaking to children about

determination, he would say:

“Lots of times when

I’ve done 41/2 miles and don’t want to go that other half, I say to

myself: ‘Nobody would know but me.’ But brother, that’s the last guy I

want to fool!”

———

%uFFFD2011 The Philadelphia Inquirer

Visit The Philadelphia Inquirer at www.philly.com

Distributed by MCT Information Services