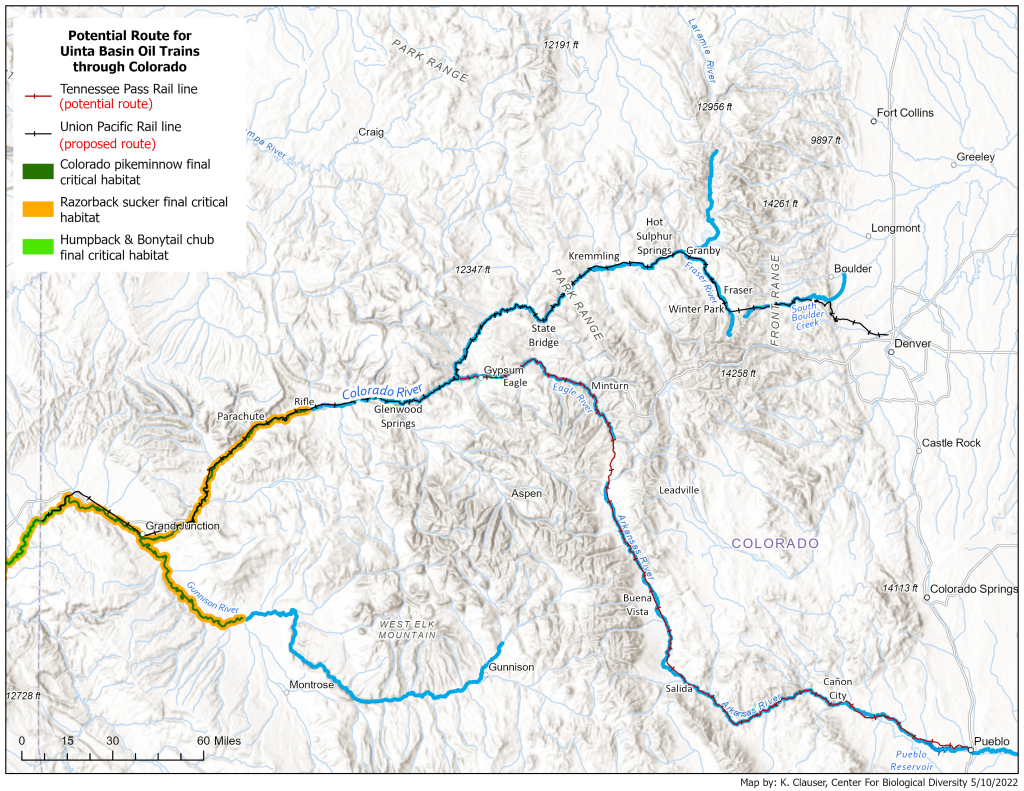

A proposed 85-mile oil railway through Ashley National Forest, in the northeast corner of Utah, is on the cusp of final approval from federal agencies. The Uinta Basin Railway project intends to connect the oil-rich but hard-to-access region to refineries on the Gulf Coast by linking the basin to an existing line. The route would then chart a course east beside the Colorado River, through flood and rockslide-prone Glenwood Canyon and onwards past South Boulder Creek and into downtown Denver before heading south.

Up to five 2-mile-long trains would traverse it each day, carrying crude oil. A federal analysis predicts that accidents are likely to occur once a year on the segment from Kyune, Utah, to Grand Junction, Colorado, with the portion between Grand Junction and Denver experiencing one every two years. Up to 2,000 new oil wells would need to be drilled in the Uinta Basin to make the project economically viable.

A coalition of seven fossil fuel-producing counties in Utah have allied with Drexel Hamilton, a New York investment bank, to promote the railway, and Rio Grande Pacific would manage train operations on the new Utah section as well as on the existing Union Pacific line through Colorado. The Ute Indian Tribe also holds a small equity stake in the project, since the nation has an economic interest in oil extracted from Uintah and Ouray reservation land.

Too sludgy for pipelines, the viscous petroleum can only be moved by train and truck. Some consider waxy crude “clean-up friendly” because it must be heated to flow and tends to form globules, rather than oil slicks, when it encounters water, making remediation easier.

But critics are concerned about how a derailment of the toxic material would affect the Colorado River, a major artery of Western agriculture and the source of drinking water for 40 million people. Roughly 150 miles of preexisting track line the Colorado River, and other stretches run through the headwaters of the river system. The federal environmental impact study did not examine the consequences of a spill in Colorado, nor the downstream effects a crash could have on the seven states that rely on the river’s water. The study that accompanied the rail line’s approval in 2021 confined its most comprehensive impact analysis to Utah.

Environmental groups, Colorado communities — including Boulder County — and politicians have seized on that omission in a last-ditch effort to stall the railway. “The last thing in the world we should be doing is jeopardizing that water source,” said Deeda Seed, a campaigner at the Center for Biological Diversity, one of the environmental groups involved in lawsuits against the railway.

The February train derailment in East Palestine, Ohio, alarmed Matt Scherr, Eagle County’s commissioner. “After what happened there, we can’t ever believe that they’re taking the risks seriously,” Scherr says. Still, attempts to thwart the project preceded East Palestine’s crash. The impetus behind Eagle County’s lawsuit is simple, Scherr says: “It’s just math. With greater volume, there will be more accidents.” Union Pacific would not comment on whether waxy crude and other petroleum products are already transported along the route. The rail operator “is required by federal law to transport chemicals and other hazardous commodities that Americans use daily, including fertilizer, ethanol, crude oil and chlorine,” a representative said in an email.

Early last year, Eagle County, with the Center for Biological Diversity, launched a legal challenge against the Surface Transportation Board, which arbitrates disputes on transit projects, arguing that the environmental impact study neglected to fully account for the risks posed to Colorado. A judge won’t hear the case until sometime this fall.

Meanwhile, Sen. Michael Bennet and Rep. Joe Neguse have been writing letters to anyone in the Biden administration who could intervene to stop the railway. They wrote Brenda Mallory, who chairs the Council on Environmental Quality, to request an environmental study focusing on Colorado’s watershed and noted that an oil spill in the Colorado River would be “catastrophic.” They also highlighted the West’s extreme drought conditions and how wildfires could spark from a crash. In 2020, the Grizzly Creek blaze — likely started by a flicked cigarette butt or sparks from a dragging trailer chain — burned the same section of Glenwood Canyon where the oil trains would pass. But money, or the lack of it, could also stop the project in its tracks. In promotional materials for the railway, the coalition of counties behind the project promised “private pays for it,” indicating the costs of construction and operation likely wouldn’t fall to taxpayers. But then the estimated costs doubled, and last week the coalition applied for more than $2 billion in tax-exempt government bonds.

Deeda Seed thinks this could be a sign of trouble for the sprawling oil route. “The efforts to secure these bonds show how fragile the financing of this railway is. They never represented to the public before that anything like this would be needed,” Seed says. The bonds are normally issued by the U.S. Department of Transportation for projects with clear public benefits — like bridges or bus lanes — and would cost taxpayers $80 million per year.

Bennet and Neguse leaned on the news of the bonds to once again ask the federal government to intervene. In a March 9 letter to Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg, they implored him to use his authority to block access to the bonds, citing the project’s failure to provide public value.

“The additional risks posed by this project … have gained new urgency in the wake of the East Palestine disaster,” the politicians wrote. It would “irretrievably sink taxpayer dollars into a project that has proven unable to contain its own costs.”