Twenty years ago, Boulder County granted a special use permit that allowed a company to mine gravel on about 650 acres between Lyons and Longmont in three phases over 33 years.

Despite having the permit, mining on that parcel of land stopped in 2001, only three years in. The original company was sold and then sold again. Martin Marietta Materials, which now owns the land, has submitted plans to once again mine gravel on a segment of that parcel.

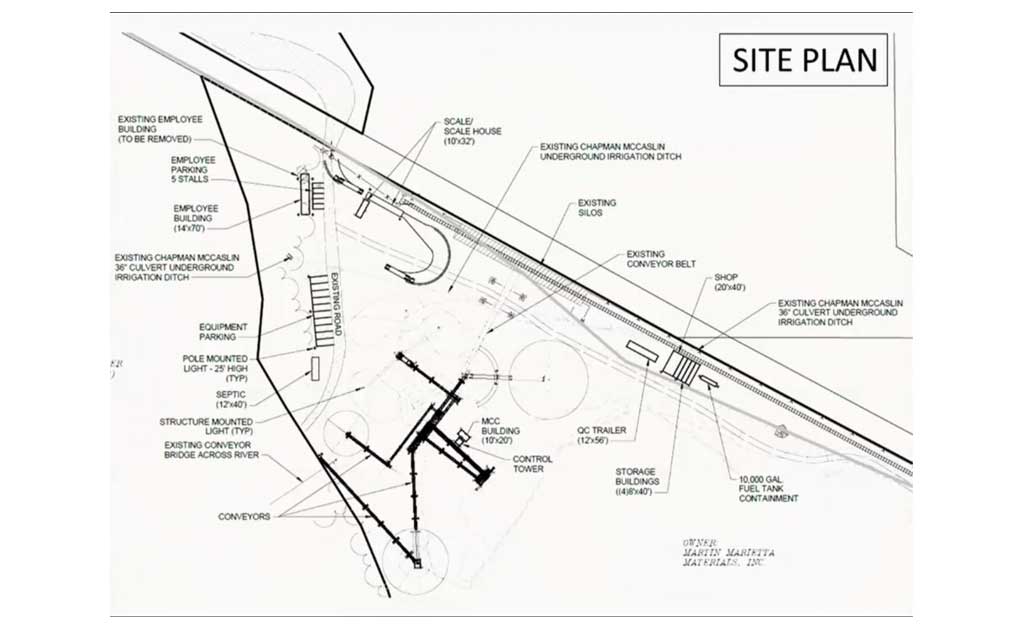

Last January, the Boulder County Board of Commissioners approved the Site Plan for that project — the “Rockin’ WP” gravel mine. If the project gets final approval, it’ll bring 20-foot-tall lights, a decently sized processing plant and mining operations to North Boulder County for the next 10 years.

It wasn’t soon after the Site Plan was approved that residents living near the proposed mining activities cried foul. Not only would the light pollution impact their quality of lives (the County, in its approval, allowed lights from 6 a.m.-8 p.m.), but the project could impact water quality, traffic on Ute Highway and potentially imperil sensitive species populations, including bald eagles, they said.

So the citizen group Save Our St. Vrain Valley (SOSVV) formed, and asked the County Land Use Department to invalidate Martin Marietta’s permit, citing the Land Use Code that says if the land isn’t used for any consecutive five year period, the permit is voided.

Amanda Dumenigo is the executive director of SOSVV and lives near the proposed mine. She says she knows there haven’t been any mining operations for close to 20 years because she drives past the site every day.

In response, the County asked Martin Marietta to submit evidence of the fact that there have been operations on the land that would allow it to keep the permit. And Martin Marietta, through attorneys, submitted a long list of supposed actions — reclamation projects like reseeding and weeding; maintenance projects like prairie dog management; and state-mandated actions like water testing and submitting administrative fees.

SOSVV was nonplussed.

“In any event,” Mark Lacis, an attorney representing SOSVV, wrote the County, “the permitholder’s response confirms that no gravel or sand has been mined, extracted, processed, and/or hauled from the site since 2001.”

Martin Marietta’s attorneys didn’t take exception to that. In fact, a state agency required the mine’s previous owner to classify the mine as in “temporary cessation.”

And yet, after getting all the materials from Martin Marietta, County Land Use Director Dale Case ruled that the mine had not experienced the damning five-year lapse, and thus the company would not have its permit voided. SOSVV appealed, and last week, the County Board of Adjustment took up the hearing.

Let’s take a step back for just a minute, because what this will eventually boil down to is a semantic argument about what constitutes “activity.” Certainly there are concerns with the mine that are specific to the neighbors who will have to deal with the increased traffic, noise and refuse of the mine, but there are also broader concerns.

Dumenigo points out that the area is still not recovered from the 2013 floods. To renew industrial activity in light of what the County knows can happen when a flood of that magnitude strikes is folly, she says.

“It’s not a matter of if it will flood again, but when it will flood again,” Domenigo says.

Matt Condon lives in the first house downstream from the proposed mining site.

“The point of the struggle over this proposed mine is not that mines should not exist, but that they need to be located in places that are the least sensitive to the environmental impact they produce,” Condon says. “This mine is smack-dab in the middle of one of the most sensitive environments that can exist in Colorado. This is especially true since the flood occurred in this very area.”

Condon says he’ll personally employ hydrologists to test river water before and after mining operations commence (if they do).

Too, archaeological and biological discoveries have been made in the area since the permit was initially granted. If known before 1998, these discoveries might have impacted the scope of the decision.

Lane wrote in a letter requesting U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service consultation that the area has a high density of Preble’s Meadow jumping mouse, as well as a high-profile bald eagle nest.

And then there are concerns about population growth — the rate of Boulder County’s housing expansion was much lower in 1998 than it is today, and mining operations could have a big impact on both new housing locations in East Longmont and the increasing number of people who use Ute Highway to commute to work.

But, again, all of these considerations were put aside on July 2., Instead, lawyers for both sides argued in front of the Board of Adjustment about how much activity Martin Marietta and previous owners had to have done on the site to keep the permit active.

To be precise, County code states that a permit is inactive “if there has been no activity under any portion of the special use permit for a continuous period of five years or more.”

Case, in his initial determination, said that activity isn’t limited to mining, but includes pre- and post-mining activity, which Martin Marietta proved the mine’s previous owners had done.

But James Silvestro, arguing on behalf of SOSVV, said that because none of the activities the mine’s owners were doing on the property required the special use permit, then they couldn’t be considered activities that would uphold that permit.

Silvestro also argued that the five-year lapse provision was codified so that Boulder County residents wouldn’t be subject to years of industrial activity. Special use permits are granted because an individual or company wants to do something outside of what has been determined acceptable by the Land Use Code. Yes, the mine’s owners weeded and grew grass and filed permits, but the special use permit was for mining, and that hadn’t been done in 17 years, Silvestro argued.

“If you’re not going to use (the five-year lapse provision) in this situation … when is this provision ever going to apply?” he asked. “If 15, 16, 17 years of non-use isn’t a lapse of a permit, then there’s really not going to be any situation where it has happened.”

In response, Mark Mathews, outside counsel for Martin Marietta, argued that reclamation work like reseeding and weeding is real work. He argued that Silvestro and SOSVV were putting their own words into what County law said — “no activity under any portion” of the permit would invalidate it, but clearly the mine’s owners had done some activity, even if it wasn’t mining, Mathews argued.

The Board of Adjustment deliberated. Board members Eric Moutz and Kari Stoltzfus took the side of SOSVV.

“If Martin Marietta wants to mine gravel, … the County needs to make sure this is still an appropriate use,” Moutz said. “I have no sympathy for Martin Marietta’s purported loss of property rights … because Martin Marietta has known all along there … was an issue concerning the validity of this permit.”

“Logging the bare minimus of land ownership does not constitute activity under any portion of the special use permit,” Stoltzfus said. “Reseeding does not count. … Martin Marietta and previous owning companies, them still being in business and them maintaining their permits does not count as activity under the special use permit.”

Scott Rudge and James Greer sided with Martin Marietta and the County’s original determination.

Rudge lamented that “our land use permits are not very clear. It would help me a lot if land use permits said, ‘Here are the uses that prevent lapse in use.’”

Both Rudge and Greer said they pored through the documents Martin Marietta provided and found countless examples of activity that met the permit’s requirements.

Janell Flaig sided with SOSVV as well, ultimately giving that side a 3-2 majority. However, to overturn a County Land Use decision, four out of the five board members had to agree to overturn. Thus, the Board denied SOSVV’s appeal.

That all said, Martin Marietta is still five years out, at least, on mining gravel in the area, which was a point Case and others made throughout the process.

“They (Martin Marietta) want to begin soon,” Case said. “Prior to mining, there’s a five-year review. Also a requirement is they need to form a neighborhood advisory group. That would push the timing out on this quite a bit.”

The Boulder County Planning Commission and Board of Commissioners will review the next phase of mining in public hearings before Martin Marietta is allowed to proceed. This is where new conditions may be imposed, or old conditions may be tweaked so as to accommodate environmental and social considerations.