Southeast winds were slowly pushing the oil toward

Authorities mounted a defense of coastal wetlands from both the air and sea as oil drifted within five miles of shore.

“Sandbags are getting filled, and we’ll be airlifting them,” said

Booms were loaded aboard shrimping vessels and sent to string floating barriers along the fragile islands offshore.

Helicopters were poised to dump sandbags on beaches,

trapping whatever splashed ashore before it could foul the fragile

wetlands that have yet to recover from Hurricane Katrina in 2005.

Preparations continue as oil giant BP works to try

and stem the leaking well spewing oil a mile below the surface. Experts

appear to have no certain plan for sealing anytime soon the runaway

well 5,000 feet below the Gulf’s surface.

“There’s a lot of techniques available to us. The

challenge with all of them is, as you said, they haven’t been done in

5,000 feet of water,”

With what had been thought to be the best immediate

solution to contain the leak, a 78-ton steel and concrete box known as

a cofferdam, resting useless on the sea floor, BP said the next best

way to contain the oil could be in the form of a smaller containment

dome.

The “top hat” was originally supposed to be part of the 78-ton containment dome.

It is on shore being modified and could be lowered over the leak sometime midweek, said

The larger dome failed when ice-like crystals,

called hydrates, formed in the top, clogging the dome and making it too

buoyant to form an effective seal.

The smaller dome would be connected to a ship, so

hot water could be pumped down as the dome is being placed to limit the

formation of the hydrates.

On Sunday, a top

suggested that experts might try to cork one of the two existing leaks

by stuffing shredded tires, golf balls and other debris into the well’s

failed blowout preventer. That option, called a “junk shot” is another

option being considered by BP.

Executives of BP, the leaking well’s owner, said

earlier that such a move could make things worse by damaging whatever

part of the blowout preventer was still working.

“I have every confidence we’ll find a good temporary

solution,” Proegler said. “We certainly have every hope and prayer that

we find a solution as soon as possible to mitigate the oil flow.”

Eleven people died in the

In the weeks since, drifting oil has spurred frenzied preparations from

Those preparations continued apace on Monday, as forecasts from the

As it inches closer, the slick is being watched in southern

with the attention usually reserved for an approaching hurricane,

though the oil is a calamity in slow-motion, threatening environmental

hazards and economic pain that could last for years.

Already, some of the richest fishing grounds of the

Gulf are off-limits, idling thousands of commercial fishermen. On the

other end of the supply line, some restaurants in the gourmet districts

of

If oil fouls marshland, extracting it would be a monumental task, likely doomed to only limited effectiveness.

Traces of oil have already been found in offshore island ramparts like

States of emergency have been declared in coastal parishes and the

Hundreds of miles away in

at a morning briefing, local and state officials said they are bracing

for oil to come ashore — but hope it can be stopped before it hits the

state.

“Let’s hope they can cut it off,” Sen.

The key question on politicians’ minds: When will the spill reach

That’s difficult to predict, said

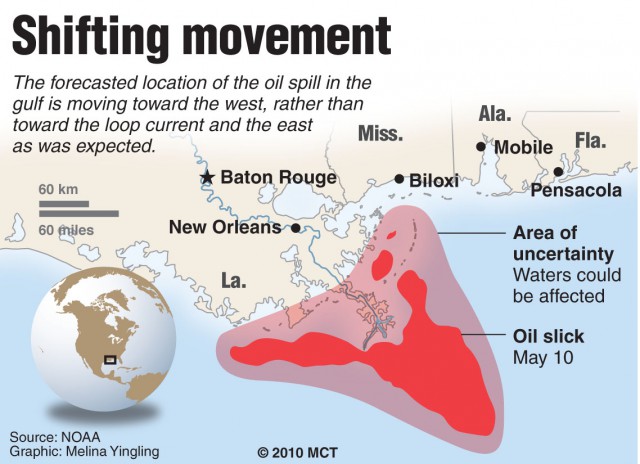

Currently, the spill is more than 100 miles from the “loop current” which gets its name from the fact that it loops around the

Any major changes in wind or weather patterns such

as a cold front or a hurricane could change that prediction,

Kamenkovich said.

“It’s highly unpredictable,” he said.

———

(c) 2010, The Miami Herald.

Visit

Distributed by McClatchy-Tribune Information Services.