When the Spanish came to the Cajamarca region of Peru looking for gold, they found the vast Incan empire instead. By 1532, Francisco Pizzaro and his men had captured the last indigenous emperor, taken his gold, and the Spanish conquest of the Incas was all but complete.

According to myth, however, the Incas hid some of their wealth in nearby lakes, counting on spirits living in the water to protect the gold.

Centuries later, these lakes are still the cultural and spiritual epicenter for the indigenous campisenos who survive as subsistence farmers nearby. And in recent years, four lakes above Cajamarca have been threatened once again by foreigners looking for gold.

Máxima Acuña lives in the hills above Cajamarca, roughly 500 miles north of Lima, in the heart of the Andes. Along with her husband, four children and granddaughter, Acuña spends her days cultivating the land and tending to her sheep, making daily walks to Laguna Azul and the other three lakes nearby.

“I walk around nature, I love being here with my plants, my animals, being outside. I go walk down to the lakes,” she says in a translated email to Boulder Weekly. “The lakes are life. The water, nature, environment is life. We go down to the lakes, drink the water, we use the water for everything, the lakes give life to everyone here.”

Acuña and her family live and work a 60-acre plot of land in Tragadero Grande, claiming they purchased the property in 1994 with the land deed to prove it. But Denver-based Newmont Mining Company, along with its Peruvian partner Minas Buenaventura, says it purchased the Tragadero Grande land in 1996/97 from the Sorochuco community, with plans to access the gold buried beneath the lakes by developing the $4.8 billion Conga mine.

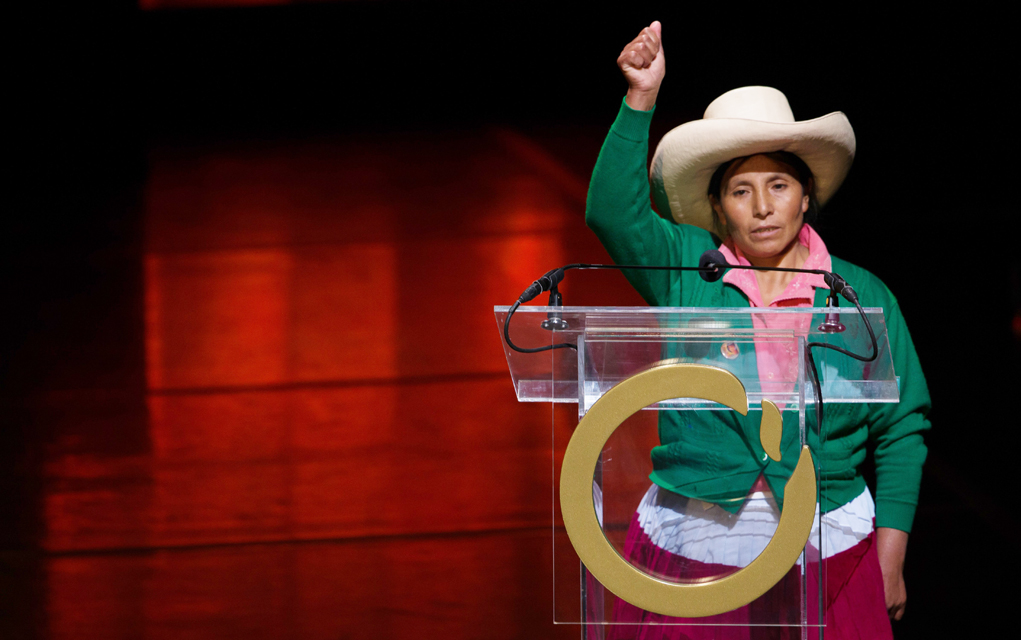

An ongoing land dispute has ensued, gaining both national and international attention, most notably when Acuña received the Goldman Environmental Prize on April 18.

“I am a woman from the highlands who lives in the mountain ranges/Tending to my sheep in mist and heavy rain/ When my dog barked, the police arrived,” Acuña sang at the Goldman awards ceremony. A woman short in stature, her traditional wide-brimmed hat barely rising above the podium, her eyes brimmed with tears as she sang. “My hut, they burned down/My things, they took away/Food, I did not eat only water I drank/A bed, I did not have with hay I covered myself/Because I defend my lakes, they want to take my life.”

Acuña has told her story countless times — police arriving at her door, destroying her crops, beating her and her family, threatening them unless they vacate the land. She says they continue to threaten her, at one point almost killing her dog, and continue to destroy her property while also maintaining a fence around her plot, causing her to feel trapped on her own land. She says the police (sometimes calling them “thugs”) are working at the behest of the mining companies.

“Here in Peru there is a law that permits the companies to hire the police as their private security forces,” says Ximena Warnaars, Amazon program coordinator for EarthRights International, a nonprofit seeking to protect both human rights and the environment through legal actions and advocacy campaigns. “That is also one of the issues … When are the police working as a civil servants and when are they working as private security?”

While Acuña and her family maintain the mining company burned their house and took their belongings, Newmont argues the family is illegally squatting on the land. In 2011, local courts ruled on the side of Newmont, charging Acuña and her husband with aggravated usurpation, or taking land through the use of force. She was sentenced to almost three years in prison, charged a reparation fine of almost $2,000 and was issued an order of eviction. Through a variety of appeals, a judge in Cajamarca later ruled there was no evidence that Acuña and her family committed a crime and overturned the order of eviction in 2014. But Newmont has appealed to the Peruvian Supreme Court, says Omar Jabara from Newmont’s corporate communications office in Denver, and land ownership has yet to be determined.

The company first proposed the nearby Conga mine project in 2010 with plans to significantly alter four mountain lakes in order to access the gold buried beneath the waters. Newmont and Buenaventura already operate the nearby Yanacocha mine, South America’s largest open pit gold mine producing roughly 471,000 ounces of gold a year. The Conga mine was expected to yield 680,000 ounces of gold and 235 million pounds of copper each year.

“Two lakes would’ve had to been relocated. Essentially the water would have been moved into a new reservoir and there were two lakes that would’ve been expanded,” Jabara says. The company has already spent $20 million in order to expand Chailhuagon Lake into a reservoir. The Chailhuagon Reservoir now provides water to the community year-round, where as the lake didn’t produce enough water to sustain the six month dry season, Jabara says.

“The plan was to quadruple the volume of water to make up for the relocating of the lakes,” he says. “Part of the plan was to expand the available water capacity from what it was as an improved benefit so that local communities would gain some benefits from the mine.”

However, opponents of the project say Acuña’s beloved Laguna Azul would have been drained and turned into a waste storage pit, threatening significant headwaters and the surrounding wetland ecosystem. The community has also resisted the mine’s development.

As Newmont began the process of environmental studies and permitting through Peru’s Ministry of the Environment, a small community of local farmers calling themselves the Guardians of the Lakes began holding vigils in 2012, funded in small part by Boulder’s Global Greengrants Fund (GGF). Acuña and her family often joined the protests.

“She doesn’t really aspire to be a leader or be a political figure,”Warnaars says about Acuña. “She’s just a farmer who is protecting her land. She’s just become a symbol for all of Peru of these struggles.”

The Guardians of the Lakes also organized a national march in opposition to the project, with support of the regional government,Warnaars says. Along with her work at EarthRights,Warnaars is also an advisor for Andes Board at GGF.

“People walked from Cajamarca all the way to Lima demanding that water be protected,” she says. “This water march was national and it was really strategic that people mobilized not around being anti-mining but being in favor of protecting their water. So with this kind of discourse they were able to gain loads of support from different organizations and communities, even people in the outskirts of Lima who have issues with water. It brought a lot of attention to the issues related to Conga.”

In addition to water issues, the proposed Conga mine has also raised questions of indigenous peoples’ rights under international law. Although the people of the Amazon region of Peru are recognized as indigenous, with certain rights and privileges such as consultation over land use,Warnaars says the people of the Andes don’t have the same recognition, as they identify more with their cultural lifestyle than with their indigenous ethnicity.

“They’d rather recognize themselves through activity as farmers,” she says. “But their identity as farmers doesn’t obviously have the same weight as being indigenous people under the law.

“The farming communities in Cajamarca have a difficult time saying they are indigenous and these are our rights,” she continues. “The government also has a difficulty recognizing them as indigenous people even though there are certain laws that could be interpreted in that way. In this kind of situation, the only thing that people have living there is the titles to their land and this is what Maxima has.”

While Newmont continues to contest land ownership through the courts, the company announced in February 2016 that the Conga mine project would be suspended, with no foreseeable plans to develop the site further amidst the social backlash and in light of expiring permits.

“Conditions for moving forward with the project would need to be securing social acceptance, project economics and bringing in a third partner to help pay for the cost and defray risks,” Jabara says. “Without those conditions, we’re not moving forward with the project.”

While this is seen as a victory for the indigenous and environmental communities, Acuña’s fight is far from over. Regardless, she’s said she will continue her struggle against corporate power, although she’d rather go back to living peacefully on her land.

“I feel proud and the [Goldman] Prize gave me more courage and encouragement so that we don’t have to feel fear anymore,” she says. “I am hopeful to have peace and tranquility, and to continue defending life, nature, water.”