While most of the country, and world for that matter, has been singularly focused on the presidential election, plenty happened with ballot measures both in Colorado and Boulder County on Nov. 3 that is worth mentioning. Statewide, we saw the defeat of Proposition 115, which would have banned abortions after 22 weeks, and a majority of voters support the passage of Proposition 118, Paid Family Medical Leave Insurance Program, which will undoubtedly change the lives of Colorado workers, and those that rely on them, for the better. Coloradans also approved Amendment 76, changing the state constitution to say that “only” citizens can vote, despite widespread opposition from civil and immigrant rights groups. We also saw the University of Colorado’s Board of Regents flip Democrat for the first time in four decades, which could be crucial in the face of mounting challenges posed by the pandemic as they govern the four-campus university system.

Locally, Longmont voters approved Ballot Question 3D, changing the City’s charter to extend city-owned property leases to 30 years, reversing a similar vote in 2019, in which citizens rejected the ballot question. In Boulder, voters overwhelmingly decided to change the mayoral selection process in favor of direct election through ranked choice voting starting in 2023, and also approved No Evictions Without Representation, which will establish a legal relief fund for tenants (see, News, “Taking initiative,” Feb. 27, and “On dangerous ground,” Aug. 6.) While election results won’t be officially certified by the Secretary of State’s Office until Nov. 30, here’s a deeper look at a few more local and statewide ballot measures that are presumed to have passed, and what it could mean for the future of Boulder County, the state and the nation.

City of Boulder Ballot Question 2C (Public Service Company Franchise/Settlement with Xcel) and City of Boulder Ballot Question 2D (Repurpose the Utility Occupation Tax)

Boulder voters approved a negotiated franchise agreement with Xcel Energy, the city’s primary energy provider, effectively ending the decade-long quest to develop a municipal electric utility. When all is said and done, the municipalization effort will cost the City approximately $25 million, paid for by the utility occupancy tax, which voters first approved in 2010 and extended again this year, redirecting current and future funds from the tax to pursue alternative energy projects in hopes of meeting the City’s 100% renewable energy goal by 2030.

City officials met with Xcel executives on Tuesday, Nov. 10 to formally launch the partnership, although it won’t be finalized until City Council certifies the election results and votes on the franchise agreement at the Dec. 1 meeting. The Public Utilities Commission (PUC) also has to approve the agreement, which is expected to happen “pro forma” sometime in January or February, although it will retroactively begin Jan. 1, according to Mayor Pro Tem Bob Yates who, along with Mayor Sam Weaver, negotiated the agreement earlier this year.

“The voters have spoken, and they’ve told the City staff and City Council what they would like to do,” Yates says. “And so we’re getting started right now.”

While the process will play out over several years, the work has already begun. First, municipalization efforts are winding down as the final bills are being processed and paid, and City staff begins archiving the work of the last 10 years: “In case we return to municipalization at some point in time in the future, that work is not wasted,” Yates says.

Although that doesn’t quite exhaust the funds generated by Boulder’s utility occupation tax over the last decade (approximately $29 million, according to Yates,) combined with new revenue from the 2020 voter-approved utility occupation tax (approximately $2 million a year until 2025), these funds will be used to pay off the rest of the muni’s bills, reimburse the City’s general fund $1.4 million, invest in new climate initiatives to help Boulder achieve its renewable energy goals and, lastly, help subsidize energy bills and access to renewables for low income families.

“It’s always our intent to cooperate and work closely with the City as we have in the past,” says Susan Peterson with Empower our Future, a broad coalition of community members and elected officials who opposed the franchise agreement. “In particular, we would like to see more detail and more community involvement in terms of defining exactly what those projects would look like when they would occur, how much they would cost the community of Boulder, et cetera.”

Of particular concern, she says, are details about the community advisory committee that will work with City officials and Xcel executives, especially when it comes to pursuing alternative energy projects in the city. “We want to see what the community engagement looks like,” Peterson says. “There’s really been no statement about how those community representatives would be selected or what that would look like. And we feel that that’s really important to understand.”

Yates says the exact role of the community advisory committee is yet to be determined but he expects that to be finalized in the coming weeks, with applications open by the end of the year and appointments made by mid- to late-winter.

But at this point, specific climate initiatives that will come out of 2C are yet to be determined, although the City is working with Xcel to develop an R&D renewable energy distribution project as the Alpine Balsam neighborhood is torn down and rebuilt within the next few years, Yates says. Depending on what ends up being ultimately successful, then “Xcel and other communities can then replicate that and create more resilient and more sustainable systems in their own cities,” he says. “And I think this is an opportunity for us to use certain projects we’ve already identified, but it’s also a process for the two parties to work together, to identify further projects next year, the year after, five years from now, 10 years from now.”

Yates says City officials are also starting on plans with Xcel to begin $33 million of work in the City to underground power lines vulnerable to inclement and climate-change driven weather, which can tend to leave parts of the city without power. Additionally, Xcel has agreed to lobby state government in the 2021 legislative session to change state law that disallows rooftop solar from generating more than 120% of the building’s energy needs, Yates says.

“Xcel advocated for the establishment of the 120% cap, so I’m hopeful we can make changes now that they’ve committed to supporting its removal,” says state Senator Steve Fenberg, who was re-elected this year and plans to introduce the legislation. “I believe we should do everything we can to promote the fast adoption of as much renewable energy as possible, and this is one easy step we can take to do that.”

Fenberg, who did not endorse 2C, also plans on introducing a whole host of “legislative changes to accelerate the adoption of renewables in Colorado,” once the next session starts in January.

While the franchise agreement only requires Xcel to reduce carbon emissions by 80% before 2030, in August, the City released indicative pricing bids for wind, solar and storage 100% renewable energy projects that are 8-15% lower than they were in 2018 as part of the municipalization effort. While these really have no bearing now, considering voters effectively terminated the muni on Nov. 3, they could come into play to help Boulder reach its goal of 100% renewable energy by 2030 should state legislature approve community-based energy procurement.

“It’s like having your own municipal utility from the standpoint of being able to control pricing and renewables without the headache of actually having to operate and maintain the poles and wires,” Yates says.

It’s an effort State Rep. Edie Hooten, also just re-elected, has been working on for a few years. Although a bill this year failed to pass due to the coronavirus pandemic, Hooten is proposing legislation in 2021 to study the efficacy of community choice energy. In this model, Xcel would still own and operate its infrastructure from transmission to distribution to billing and customer service. But it would allow jurisdictions to choose where they procure energy from, including renewable projects from other operators.

Hooten’s bill would require the PUC to consider approximately 20 specific questions about community choice energy, involving a “very transparent, robust” stakeholder process and public meeting. If such a bill passes, the PUC would have until the end of 2021 to present its findings to the legislature, so it would be 2022 before any substantial enabling legislation could be introduced, and a few more years before the PUC would finalize any rulemakings.

“We’re probably looking at 2024 before communities could actually even take advantage of” community choice energy, Hooten says. But the process alone would incentivize investor-owned utilities, like Xcel, to transition more quickly to renewables. “It puts pressure on them to meet the local energy goals of communities like Boulder,” she says.

Hooten opposed the franchise agreement for its lack of community control, but says now that voters approved it, “It’s definitely a step in the right direction of more local control and a more open, competitive market for electricity generation.”

Proposition 113 (Adopt Agreement to Elect U.S. President By National Popular Vote)

This was a referendum vote, brought to the 2020 ballot by citizens who disagreed with Democratic state legislators and Gov. Jared Polis, who entered Colorado into the National Popular Vote (NPV) Interstate Compact in 2019. But Coloradans sided with elected officials on Nov. 3, with 52.16% of the voters approving the measure, according to the latest Secretary of State numbers.

“We kept hearing time and time and time again that most Coloradans were against it,” says state Senator Mike Foote, of Boulder County, who introduced the NPV bill on the first day of the 2019 session. “And as it turns out, of course, most Coloradans are for it because the national popular vote is in fact a popular idea. So, I feel very good that we were able to get that kind of vindication.”

Despite the fact that elected Republican legislators oppose NPV across the board in Colorado, “We could not pass this if it weren’t for some conservative votes,” Foote adds. “If you look at conservative counties across the state, we did pretty well.” Although NPV didn’t pass in any of those counties, it did get 40% of the vote in El Paso County and 35% in Mesa County, which was also the epicenter of the referendum effort.

Colorado’s nine electoral votes for president are now committed to the winner of the national popular vote — regardless of who wins the statewide popular vote — in future elections should the Interstate Compact be ratified. In order to become legally binding, enough states need to sign onto the Compact to account for 270 electoral votes, the majority needed in order to guarantee the presidency. The NPV Compact does not abolish the Electoral College, but rather circumvents it, changing the way the electors are used under the states’ rights section of the Constitution, which guarantees their exclusive authority to allocate the electors in the way they see fit, as recently confirmed by the U.S. Supreme Court.

Although the NPV legislation has been introduced in all 50 state legislatures since 2006, it has seen varying degrees of success. Currently, the Compact has 196 electoral votes from Delaware, Hawaii, Rhode Island, Vermont, Connecticut, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New Mexico, Oregon, Washington, California, Illinois, New York and the District of Columbia. It needs an additional 74 electoral votes to go into effect, which could come from a variety of smaller states adopting it or could take just a few larger ones like Texas or Florida coming on board.

The Colorado ballot question was the first time, however, that the NPV idea has been passed by voters, and many of its proponents see the win in Colorado as a blueprint in states where the legislature has been reluctant to sign on.

“One thing about the National Popular Vote organization has been that they’ve just been persistent, and they’ve always looked at it as a long-term project,” Foote says. “It’s not something that’s going to happen overnight.”

For all intents and purposes, the Colorado vote approving Proposition 113 doesn’t change much. If and when enough states sign onto the NPV Compact, however, the entire presidential election process will be different.

“America’s legislators should take notice,” Dr. John Koza, chairman of National Popular Vote, said in a press release. “The voters want a national popular vote for president. They want to compel the candidates to campaign in all 50 states. They want every voter in every state to be relevant in every presidential election. The National Popular Vote Interstate Compact delivers on all these promises and can be in place for the 2024 presidential election.”

Proposition 114 (Reintroduction and Management of Gray Wolves)

The planning process to reintroduce gray wolves in the Centennial State has begun. On Nov. 3, Proposition 114 narrowly passed, 50.64% to 49.36%, according to the Secretary of State’s unofficial election results, marking the first time a species will be reintroduced to an ecosystem by voter consent. Soon after, Colorado Parks and Wildlife (CPW) announced its intent to begin the process, the first step of which will be for the CPW Commission to develop a management plan introducing the gray wolf onto designated lands on the Western Slope by Dec. 31, 2023. Currently, no such plan exists and a schedule of required statewide hearings about scientific, economic and social considerations has yet to be published.

“Our agency consists of some of the best and brightest in the field of wildlife management and conservation,” said CPW Director Dan Prenzlow in a press release. “CPW is committed to developing a comprehensive plan and in order to do that, we will need input from Coloradans across our state. We are evaluating the best path forward to ensure that all statewide interests are well represented.”

Prenzlow sits on the CPW Commission along with other governor-appointed members from ranching, agriculture, outfitting, hunting, fishing and recreation backgrounds, including the director of the Department of Natural Resources.

The narrow passage of Proposition 114 comes on the heels of the Trump administration’s announcement to delist the gray wolf from the federal endangered species list, despite the fact that the wolves have not be restored to 20% of their historic range, a key provision for delisting. As such, a coalition of Western wolf advocates have filed a notice of intent to sue the federal government.

“Given that gray wolves in the lower 48 states occupy a fraction of their historical and currently available habitat, the Fish and Wildlife Service determining they are successfully recovered does not pass the straight-face test,” John Mellgren, an attorney with the Western Environmental Law Center, said in a press release. “While the Trump administration may believe it can disregard science to promote political decisions, the law does not support such a stance.”

Opponents of Proposition 114 have not ruled out a legal challenge of their own, according to Patrick Pratt, deputy campaign manager for Coloradans Protecting Wildlife. “We have not ruled out any available options and will not make a final determination until all votes are counted,” he wrote in an email to Boulder Weekly, maintaining the organization’s stance that the reintroduction measure is “bad policy and should not have been decided by the voters.” (Election results will be finalized by the end of the month.)

Regardless, expect a lively debate around how gray wolves should be reintroduced in Colorado and how best to manage them, as the public process unfolds in the coming months and years.

Financial implications of key statewide ballot measures

Gov. Jared Polis released a $35.4 billion state budget proposal this month that includes remedies for some major cuts lawmakers had to make across the board during the pandemic. The plan includes stimulus funds for individuals and businesses, helps get education funding — 47th in the nation, in case you forgot — close to pre-pandemic levels, and stows some money away for the uncertain future.

In settling on this year’s and future budgets, however, lawmakers will have to consider the effects of a handful of ballot initiatives that passed this year, some bringing in revenue for targeted projects, while others further limiting the amount of money coming into state coffers.

Mixed bag for education funding

Perhaps the largest economic boon is the passage of Proposition EE, which puts a tax on nicotine and vaping products and uses the revenue to fund a variety of programs.

The state legislature passed a bill earlier this year raising taxes on nicotine products — cigarettes, smokeless tobacco, cigars, certain liquid nicotine as used for vaping — and because of the Taxpayer Bill of Rights, we all had to vote on it. It passed, and now a set amount of taxes will be placed on each of the nicotine products outlined in the law.

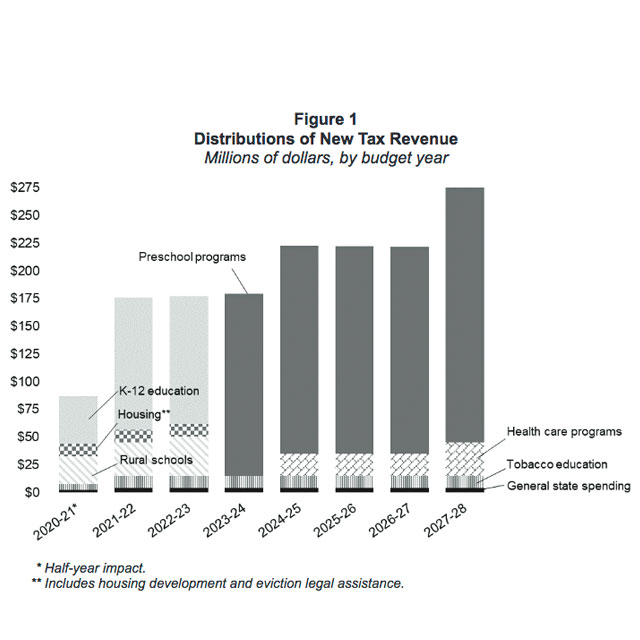

It’ll raise up to about $175.6 million in revenue next fiscal year, with an escalating amount of revenue up to $275.9 million by 2027.

Much of this funding (see chart above) will go toward education — which is critical given the cuts schools across the state had to endure during COVID-19, exacerbating the problems caused by the already low levels of funding with which they were operating.

Money will be used to provide at least 10 free hours of preschool to every child before their first year of kindergarten. A separate chunk of money will go toward rural schools, allocated on a per-pupil basis, and even more will go toward general K-12 education.

The funds will also be used, in smaller part, for housing assistance, a tobacco education program and general fund spending.

Passage of Amendment B, which repealed the Gallagher Amendment, will also impact education funding. It locks in property tax assessment rates, instead of basing them on a proportional scale that many said was hampering institutions like schools and fire districts that rely on property tax revenue.

The Colorado Education Association, the state teachers’ union, hailed the passage of the amendment, pointing out that now, “Nearly a quarter of a billion dollars will remain in Colorado public schools next year; funding desperately needed in the wake of the global COVID-19 pandemic and more than a decade of K-12 budget deficits.”

It remains to be seen just how the Gallagher Amendment repeal will impact education funding. In its assessment of the amendment, the state Legislative Council noted that the resulting higher property tax revenue will increase local financial support for school districts, while also lowering the state’s funding responsibility.

Goodbye $203 million; Hello, 40 bucks

Voters also approved Proposition 116, which will lower the state income tax rate from 4.63% to 4.55%. Because all Coloradans are taxed at the same rate, those who make under $100,000 can expect single- or double-digit annual savings on their tax bill; those who make more can expect a proportionately modest amount of savings, though obviously more.

The state’s going to lose out on $203 million in revenue this fiscal year, and $154 million next year, with future loss of revenue depending on the state’s economic performance.

The state Legislative Council found before the election that passage of Proposition 116 is going to require reductions elsewhere in the state’s general fund to make up the gap. The money coming in from the nicotine tax, remember, is earmarked for certain projects, and the Gallagher Amendment repeal windfall will be realized locally; lawmakers will have to reassess the tax landscape before determining where to cut.

Polis hailed the “tax relief” and the libertarian Independence Institute, which organized Proposition 116, hailed the measure’s passage, of course, and juxtaposed it to an effort to institute a progressive tax rate in Colorado. That measure’s defeat (before making it to the ballot) and Prop 116’s passage, “has signaled to everyone watching that Coloradans still support our flat tax and [TABOR],” the Institute wrote in a celebratory email announcing the win.

Proposition 117 passed, as well, requiring voter approval on fee-based enterprises making over $100 million in its first five years. Supporters of the bill say it will keep state-based agencies from charging high fees without recourse. In actuality, it may prevent certain enterprises from getting off the ground at all.

How does it all square?

Ultimately, it’ll be up to lawmakers to make subsequent budgets work under the new laws approved by voters. Time will tell how the Gallagher repeal works in wealthy counties versus poorer counties; how Proposition EE revenue will help fill in gaps; and how less money coming in from income tax — a sizable portion of Colorado’s state revenue — will impact what can get funded and by how much.

And, of course, there’s still a pandemic, meaning businesses from Main Street to the oil patch are going under or filing bankruptcy, leaving many people unemployed and tax revenue uncertain. Polis’ budget aims for a strong economic recovery in the next fiscal year, but by then we’ll likely have some more statewide ballot issues that’ll change the state’s revenue landscape.