If returned to El Salvador, Jaime Leon Rivas fears he’s next ‘to get killed’

When he was a little boy in El Salvador, Jaime Leon Rivas never wondered about George Washington even though the president’s face was everywhere. The U.S. dollar is the country’s official currency, but Rivas, who was poor and living with his grandparents, rarely saw any greenbacks. What he remembers seeing were bodies, dead, twisted and splayed open, the victims of the gangs. This didn’t happen in America – not in Colorado, where his mother lived and worked as a housekeeper. She carefully saved up the dollars she earned and, in 2005, when Rivas was 10, paid people smugglers – coyotes – to get her boy out.

“I didn’t know where I was going,” Rivas says. “I only knew that I was going to my mom. That’s all that mattered.”

So Rivas and one of his brothers, who was about three years older, were handed to the coyotes. Their destination, the crisp, cool air, big mountains and starry night skies of Colorado lay 2,600 miles away. And each mile was a slog as a bus rumbled over bumpy roads past weather-beaten towns into Guatemala, passing through vast, thick stretches of rainforest. Finally came Mexico. Lots of Mexico. It took days, maybe weeks, to work northward to the U.S. border. Rivas, now 19, can’t exactly recall how long it took. “I was just a kid,” he reminds.

He remembers stopping in a town to wait for more travelers to join – more people looking for a safer life or just good work; more people with money for the coyotes. When the boys crossed the Rio Grande River, it was December. They entered the United States outside of Hidalgo, Texas, a town with a history of chest-thumping Americans and Mexicans who’d make great characters for a spaghetti western. Somewhere inside the winter-barren ranchland of southern Texas, Rivas and his brother realized they were lost.

“I remember it was really cold and we were just waiting and waiting,” Rivas tells.

The coyote who was supposed to come never arrived. That was not a good place for that to happen: 500 people died crossing the border in 2005 from exposure, thirst and similar fates, according to the Border Patrol. Now alone, Rivas and his brother began to walk about aimlessly, looking for their coyote. For hours they wandered until they finally found someone – or someone found them.

“It was ICE,” Rivas tells Boulder Weekly in a phone interview from inside the U.S. immigration detention facility in Aurora.

ICE stands for U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, and the agency took the boys into custody. But the children weren’t deported. They were eventually sent to Denver in immigration proceedings where their aunt met them. Asked by a judge if the boys were ready to return to El Salvador, the aunt said, “not really.” Rivas’ mother didn’t want that. She was afraid of the gangs in that country.

So, instead, Rivas and his brother were enrolled in school in Colorado. Rivas learned English. He jumped in the snow. It seemed he was on track. Yet soon, his life began to unravel. He just couldn’t stay out of trouble.

“He was hanging out with all the wrong people and it caught up with him,” his girlfriend, Jenny Martinez, says.

Rivas’ juvenile records are sealed, but he is open about his past. His attorney confirms the details. In 2007, when Rivas was about 12, he had a misdemeanor weapons charge. In 2009, Rivas ran afoul of the law again, charged with trespassing into a vehicle, a felony. In 2011, Rivas was charged with misdemeanor criminal mischief.

That same year, though the young teen was restricted to Colorado because he was on probation, he decided, almost on a lark, to go to Los Angeles because a friend was going. He’d never been there. He’d wanted to see the beach. Thinking back, Rivas says, he was a kid running away from his very adult problems. But his troubles only followed him to L.A. There, through his friends, Rivas encountered members of the notorious, ultraviolent gang, the Mara Salvatrucha, commonly known as MS-13.

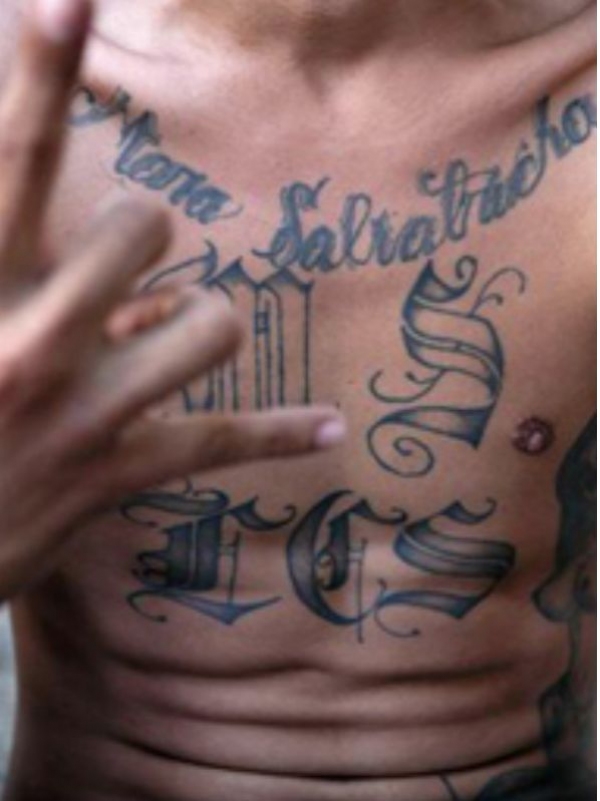

It almost seemed almost inevitable that a young runaway from the poor streets of San Salvador would fall into the hands of the MS-13, particularly in L.A. After all, the gang formed in the city during the gangland bloodbaths of the 1980s as a way for Salvadorans and other Central American immigrants to protect themselves. Through brutal machete killings and a long list of other crimes, including rape and money laundering, MS-13 members made the gang one of the most menacing ever to fall on the radar of the Federal Bureau of Investigation. And, because members of the gang were deported from the United States, they were able to establish an international network, taking over impoverished neighborhoods in Central America and using them as power seats. By 2006, FBI executive James “Chip” Burrus lamented over the crisis: “It was an eyeopening experience to see what it could come to at some point here if we don’t do our jobs correctly.”

When Burrus toured San Salvadoran gangruled neighborhoods, or “maras,” which act like micro-dictatorships, he traveled in an armored van, sharpshooters monitoring every turn down every street.

“There’s such freedom of movement between El Salvador and the United States,” Burrus noted, calling for more multi-national cooperation between enforcement organizations.

Hundreds of alleged members of the gang have been arrested in the United States since then – several in Colorado in recent years, linked by prosecutors to meth and firearms distribution. Despite the crackdowns, MS-13 continues to shock authorities with its brutality. The most recent headline emanates from Long Island, New York, where prosecutors allege members shot Vanessa Argueta to death, execution style, along with her 2-year-old boy, Diego Torres, in a dispute in which Argueta disrespected the gang. The incident is but one of scores of killings attributed to the gang’s members, known for their extreme and intimidating posturing and heavy tattoos, often over their faces, with the letters “M.S.”

There are countless alleged victims, including one from a decade ago – about the same time Rivas was dropped off in Texas. Boulder Weekly printed the story of 16-year-old Edgar Chocoy, killed in the streets of Villaneueva, a poor Guatemala town overrun by MS-13 gangsters. Chocoy, who had been lured into the gang as a boy in his home country, stood out because he had predicted his own death, telling federal immigration officials in Denver that if they deported him, he would be murdered. Chocoy explained that he had tried to distance himself from the gang by hiding with relatives and finally running away to L.A., where his mother worked. He had learned the hard way that MS-13 does not allow anyone to quit. And his ties to the gang did not seem to help his case in Denver.

“I am certain that if I had stayed in Guatemala the members of the gang MS would have killed me,” he wrote in an affidavit. “I have seen them beat people up with baseball bats and rocks and shoot at them. I know they kill people. I know they torture people with rocks and baseball bats. I know that if I am returned to Guatemala I will be tortured by them. I know that they will kill me if I am returned to Guatemala. They will kill me because I left their gang. They will kill me because I fled and did not pay them the money that they demanded.”

Just two weeks after he was deported, Chocoy was gunned down, sparking condemnation of U.S. actions in Denver by the United Nations’ high commissioner for refugees and Amnesty International.

While in L.A. in 2011, Rivas found himself amid MS-13 members. He was arrested. Because Rivas’ records are sealed, it is unclear what happened in the case, but it seems the arrest saved him. As a runaway from his family and his probation, he was returned to Colorado. He is clear that he never joined the gang and, to prove it, he never got a tattoo that intelligence analysts say is necessary for membership in the gang.

Still, ICE has labeled Rivas as somehow affiliated with the gang, according to his attorney, citing documents.

“They are trying to say I was gang affiliated,” Rivas acknowledges, making clear that he is not a member. “I’m not involved with the gang.”

After his arrest in L.A., gangs would touch Rivas’ life again. Word had come to the family that his grandfather had been shot to death by gangsters in San Salvador for failing to pay protection money. His grandmother and the rest of the family, Rivas says, went into hiding. And, in June of 2012, came news of another death. This time it was a friend in L.A., Daniel Regalado, 18, who, along with a 19-year-old man, was gunned down. The shooting appeared to be gang related, according to the Los Angeles Police Department.

The deaths literally made Rivas sick. He was already in the process of turning his life around and now he was more adamant. Gangs were not a way to build a life.

At home, he enrolled in the alternative Snowy Peaks High School in Frisco, about 10 miles north of Breckenridge. There, Rivas, set to graduate in May, turned his life around for good. He aspires to become a counselor to help troubled teens.

“I want to help young kids so they can learn the right way,” he says.

But he may never get the chance to do that. On March 4, Rivas was summoned to an ICE office in Glenwood Springs. When he arrived, he was handcuffed and hauled away to the ICE’s Denver Contract Detention Facility in Aurora.

That’s because in 2007, while still a child, he was issued what is called a “voluntary departure order” from ICE telling him to leave the United States within 90 days. Because he’s still here, he faces being deported. He may also be disqualified for years from gaining legal permanent residency, a “green card,” says his lawyer, Alexander McShiras, with the Chan Law Firm in Denver.

“He lacked the capacity to understand what he was agreeing to at the time,” McShiras says.

McShiras is asking ICE to either issue a stay or to defer action on Rivas’ case, buying him up to two years’ residence in the United States to argue the legal merits of the case. One point of contention is that Rivas’ initial immigration counsel years ago never advised his mother of the consequences her son would face for failing to leave the country. Also, the initial counsel failed to ask the boys if they had reason to be scared of returning to El Salvador.

More time is needed, McShiras adds, because he doesn’t yet have access to all the documents to properly defend his client. The attorney has made requests for documents from four agencies, including ICE, using the Freedom of Information Act, the law that gives Americans the right to access information by the federal government.

“I filed for expedited records because he is detained,” McShiras says. “Usually to get expedited records you have to show that someone is in deportation proceedings or that there is some exceptional need. He is not in proceedings, but he is detained and could be deported at any time so that is the exceptional need.”

Still, McShiras doesn’t know when – or if – all the needed records will come. ICE, he adds, almost never responds to such requests. As yet, Rivas isn’t even slated to see a judge. Ultimately, McShiras wants the feds to reopen Rivas’ case so he can apply for a “withholding of removal.” That would allow McShiras to argue, for instance, that Rivas’ anti-gang remarks were political and could trigger retaliation in El Salvador.

“If MS-13 is playing a role in controlling the country, when Jaimes says he’s opposed to gangs, it becomes a political opinion,” McShiras says. “That is to say that he is opposed to the government in El Salvador.”

That might justify an asylum claim. As U.S. ambassador Roger Noreiga, now a fellow at the American Enterprise Institute think tank in Washington, D.C., notes: MS-13 supports the FMLN ruling party in El Salvador.

“Here, too, the FMLN has troubling relationships with criminals whose activities have dangerous repercussions for the United States as well as El Salvador,” Noreiga wrote in an analysis earlier this year.

Meanwhile, those closest to Rivas in Colorado have already made up their minds. They say they have seen Rivas turn his life around. They want him to stay and they want everyone to know how they feel. On Rivas’ birthday – March 25 – dozens of supporters, including some of his schoolteachers, gathered outside the detention facility in Aurora. Some held “#FreeJaime” signs. His girlfriend, Martinez, called on President Obama to intervene in Rivas’ case.

Brett Tomlinson, Rivas’ principal at Snowy Peaks, spoke to the crowd through a bullhorn: “When Jaime made some poor choices a few years ago, the system reeled him in. They spent a lot of time – my money and your money – on helping him become a better person so he can improve his community. However, like a bingo game, the system just randomly pulled his number years later, only to detain him here in this building.”

ICE was not prepared to comment on the case by deadline, said Carl Rusnok, a spokesman for the agency.

From his cell, Rivas, who could be deported at any time, says some people think he should be sent back to in El Salvador, but his home is now here: “I have nothing there. My grandfather is gone. His house is gone. They took it all. All of that is lost.”

And he is keenly aware that his disavowing of MS-13 to ICE and elsewhere, including to the press, could cost him. It’s hard to know if it is a slight, but it is clear that the gang doesn’t take kindly to the smallest of snubs. As lawyer Jeffrey D. Corsetti wrote for The Georgetown Immigration Law Journal in his 2006 article, Marked for Death: The Maras of Central America and Those Who Flee Their Wrath: “Unfortunately, the sad truth is that the maras rarely take no for an answer. To publicly oppose the gangs, through refusal to join them or open confrontation, is to risk death, not only for oneself, but also for one’s loved ones.”

Rivas says whoever in America has the last say on his case, holds his life in their hands: “If I go back to El Salvador, I know I’m just going to get killed.”

Editor’s note: After deadline on Wednesday, Jaime Leon Rivas’ attorney learned that his client would be granted a temporary stay. This allows Rivas to be released and continue to reside in the U.S. for up to one year to continue his case against deportation. This ongoing story will be updated in BW next week.

Respond: [email protected]