Mary Smith takes a seat with her back to the crowd, some two-dozen people gathered in the third-floor hearing room of the Boulder County Courthouse. She’s facing the County Commissioners: Cindy Domenico, Deb Gardner and Elise Jones.

“Mary, you’re up,” Jones tells Smith. “You’ve seen us through this before.”

It’s been five years since Smith came before the Boulder County Commissioners and asked them to ban genetically modified organisms (GMOs) on taxpayer-funded open space. It’s a battle she and other anti-GMO activists lost the first time around — after months of debate, hundreds of written comments and a 13-hour public hearing — when the commissioners (Domenico among them, along with Ben Pearlman and Will Toor) unanimously voted to add genetically engineered sugar beets to the crops grown on county agricultural land in December 2011. (GE corn has been allowed since 2003.)

The result of that vote was an update to the Boulder County Parks and Open Space Cropland Policy, extending the use of GE corn and adding GE sugar beets to the crop mix on Open Space for five years.

Which brings us back to the third-floor hearing room. It’s around 2 p.m. on Friday, Feb. 19, 2016, and Mary Smith is speaking at the last of three days’ worth of individual public meetings between community members and the County Commissioners. She’s speaking because the Cropland Policy is up for renewal this year. These individual meetings — with activists like Smith, county farmers, biotech engineers, beekeepers, agriculturalists, professors and more — are a lead up to the first and only pubic hearing on Feb. 29 regarding whether to change the policy or stay the course with GMOs on county land.

After some 19 hours of individual meetings, and a public hearing that could last up to 10 hours, the commissioners are slated to make their decision on March 17.

On this Friday afternoon, Smith is trying to pour year’s worth of research into a 20-minute statement.

Her war speech hasn’t changed much in the past five years; her primary complaint isn’t about the safety of GMOs, though she’s not afraid to tell you they’re at the root of many ailments. No, if you ask Smith what all this time spent fighting GMOs on county land is about, she’ll tell you it’s about local sovereignty, and more importantly, how Boulder County has denied it to its citizens.

“I guarantee at that meeting on the 29th we see exactly what we saw four years ago: Farmers from across the state demanding their right to plant GMOs,” she told the Commissioners on Feb. 19. “What agricultural chemical companies have done is divide the community down the middle. … It was a travesty on so many levels, but the biggest was the [lack of] democratic process. What happened to ‘We the people’?”

While Smith’s position remains the same, what has changed is what we know about GMOs, about the effects the herbicides and pesticides used in their cultivation have on our environment and health. We know that Big Ag companies like Monsanto, and even federal agencies like the U.S. Department of Agriculture, have silenced and tormented researchers who attempt to publish critical research on the agrichemical industry’s most profitable products, or those that are in the pipeline. We know that Monsanto’s monopoly ownership over the sugar beet seed market has actually made reverting to non-GMO sugar beets for commercial production impossible at this time.

On a local level, we know that two of the current County Commissioners, Elise Jones and Deb Gardner, ran in 2011 on platforms of banning GMOs on County Open Space land. We know natural food industry players present in 2011’s great debate about GMOs on Boulder’s Open Space appear to be missing from this year’s discussion. And we know that state and county agriculture employees shared information about the upcoming hearing with farm special interest groups, well before the public was informed of the upcoming hearing.

So with all we know, the question is, what will we grow?

Let’s be clear: these questions aren’t new

While research on GMOs from the past five years has given us more reason than ever to be skeptical, scientists were questioning these products back in 1991 when the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) was developing its policy on GE foods.

In memos obtained by the Alliance for Bio-Integrity in 1998 (in preparation for a pioneering case on GMO labeling, Alliance for Bio-Integrity, et. al. v. Shalala), numerous experts within the FDA voiced their concerns about this new technology entering the marketplace. Still, GM seeds were introduced commercially in 1996.

A common argument today is that genetically engineering seeds in a laboratory is no different than cross-pollination or cross-hybridization, both methods that nature and humans use to proliferate a species or create novel traits.

But FDA microbiologist Louis Pribyl disagreed with this oversimplification in a comment on a Biotechnology Draft Document in early 1992.

“There is a profound difference between the types of unexpected effects from traditional breeding and genetic engineering which is just glanced over in this document,” Pribyl wrote. (Other comments in his memo seem to divine future concerns more than 20 years later: “It reads very pro-industry, especially in the area of unintended effects, but contains very little input from consumers and only a few answers for their concerns, many of which would be answered by supplying the scientific grounding principles.”)

And Pribyl was far from alone. In a memo to FDA Biotechnology Coordinator James Maryanski about a statement of policy on GM plants, Linda Kahl, an FDA compliance officer wrote, “I believe that there are at least two situations relative to this document in which it is trying to fit a square peg into a round hole. The first … is that the document is trying to force an ultimate conclusion that there is no difference between food modified by genetic engineering and foods modified by traditional breeding practices. This is because of the mandate to regulate the product, not the process.”

Kahl goes on to say, “The process of genetic engineering and traditional breeding are different, and according to the technical experts in the agency, they lead to different risks.” She does, however, go on to point out that these risks might very well be lower than for foods produced by traditional means, but the agency is so busy pointing out that it’s “the product and not the process that’s regulated, that risk assessment is lost.”

Scientists at the FDA were also worried about the agency’s plan to feed GE products to livestock — but there was little question about the agency’s intention to implement the seed industry’s business model, as GE crops were introduced to animal feed in 1996, along with foods for human consumption. According to a 2013 report from the National Corn Growers Association, about 80 percent of all corn grown in the U.S. is consumed by domestic and overseas livestock, poultry, fish and fuel production. Keep in mind that around 90 percent of the U.S. corn crop is genetically engineered.

Back in February 1992, Gerald Guest, the director of the FDA’s Center for Veterinary Medicine, urged (and some may read the memo as reprimanding) FDA Biotechnology Coordinator James Maryanski to support a pre-market review of GE food plants because, as Guest put it, “the new methods of genetic modification permit the introduction of genes from a wider range of sources than possible in traditional breeding,” and “new plant constituents that could be of a toxicological or environmental concern.”

Guest goes on to point out that unlike the human diet, a single plant product may constitute a significant portion of an animal’s diet, and that animals often eat parts of plants that humans don’t.

Here’s the truly disturbing part of Guest’s memo: “Generally, I would urge you to eliminate statements that suggest that the lack of information can be used as evidence for no regulatory concern.” He points to two such examples in the Draft Federal Register Notice on Food Biotechnology. Guest also calls parts of the notice “misleading” as it doesn’t include future methodology or techniques for GE goods.

“Sponsors may assume that if their transgenic product or methodology is not included in the Notice, that it is exempt from regulation.”

Despite such warnings, no pre-market review of GE food plants was conducted.

This was 1992 — 24 years ago. It’s clear the concerns of these scientists were ignored, and it seems not much has changed in nearly a quarter century.

Questions remain while forced silence reigns

Questions remain while forced silence reigns

Scientists have continued to question GMOs and the pesticides associated with their cultivation, and federal agencies— with the blessing of agricultural behemoths like Monsanto — have continued to shut those questions down and force concerned scientists out of the conversation. Much of this silencing of research has occurred since the County Commissioners made their last decision to allow GMOs on taxpayer-owned property in Boulder County five years ago.

Let’s start with Jonathan Lundgren, an entomologist with the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Agriculture Research Service (ARS).

Lundgren worked for the USDA for more than a decade, publishing nearly 100 peer-reviewed papers since beginning his career with the ARS in 2005. In 2012 he was presented with ARS’ “Outstanding Early Career Research Scientist” award and placed at the helm of his own lab.

But Lundgren made the decision to turn a critical eye to some of Big Ag’s most prominent products, namely neonicotinoids, the world’s most widely used insecticide. He also publicly questioned, in a 2013 peer-reviewed journal, a Monsanto-developed insecticidal technology that had yet to hit the market, RNA interference. RNAi, as it is often referred to, works by killing targeted insects and weeds by silencing genes critical to their survival. Lundgren and his USDA colleague Jian Duan were skeptical of the technology’s ability to target pests and leave everything else in the environment unscathed, and they noted that research on RNAi up to that point had mostly revolved around human medicine, not agricultural use.

RNAi is clearly a GE technology, but what’s the GE connection with neonicotinoids, you may wonder. Well, GE corn is often treated with neonics. The pesticide provides a second line of defense to manage pests that aren’t killed by Bt (a soil bacteria genetically inserted into corn to manage insects) or Roundup, the world’s most widely used herbicide.

Lundgren, along with numerous other researchers over the last five years, found in more than one study that neonics wreak havoc on pollinator populations, such as bees and butterflies.

All of this is background for what ultimately became the dismantling of Lundgren’s career with the USDA: In September 2014, Lundgren filed a “Complaint of Violation of USDA Scientific Integrity Policy.” In his complaint, Lundgren stated he was subjected to “improper reprisal, interference and hindrance of [his] research and career” after a series of late-March 2014 press interviews (including one with Boulder Weekly on RNAi technology, “Muzzled by Monsanto,” April 3, 2014) and a report by the Center for Food Safety in which Lundgren added his expert opinion that neonicotinoids were overused and of “questionable economic value for farmers.”

A “misconduct” investigation on Lundgren began in April 2014. He describes the investigation as “utter hell” for himself and his lab group.

“Five of my eight term employees have had their employment threatened, hampered, or were dismissed unexpectedly since March 2014,” Lundgren wrote in his complaint. “I have never had problems of this nature or to this extent as I have since talking with the press in late March.”

The following year, Lundgren was accused of submitting a paper (on the negative effect of a particular neonic on monarch butterflies) to a publication without proper internal approval from the USDA. He was subsequently found to be in violation of agency travel protocol in March 2015 when heading to a National Academy of Sciences conference to speak about the role of genetic engineering in pest management, and then on to a Pennsylvania No-Till Alliance conference in Philadelphia. Ultimately, he spent $3,000 out-of-pocket to attend both conferences, and was placed on a 14-day unpaid suspension for his transgressions in August.

Lundgren filed a federal whistleblower complaint in October. The USDA asked that the case be thrown out, but an administrative judge dubbed the case “non-frivolous,” and ordered a hearing.

As of Feb. 12, 2016, the USDA’s inspector general, Phyllis Fong, announced plans to investigate censorship of agency scientists working on controversial issues.

Lundgren is not alone in his dismissal from the scientific community after years of questioning Big Ag technology.

As mentioned earlier, Boulder Weekly wrote about RNAi technology in 2014, focusing specifically on Vicki Vance, a professor of botany at the University of South Carolina. In 2012, Vance was repeatedly harassed by Monsanto and unable to get her research published after designing a study that found animals could take up microRNA from plants, a finding that would suggest RNAi agricultural technology might warrant closer scientific inspection before hitting the market.

Vance’s study was based off of a 2011 study by Chen-Yu Zhang of Nanjing University in China. Zhang’s study also showed that mammals (mice) could take up small RNAs when they eat plants, and those plant RNAs regulate expression of the mammal’s genes. The team found a particular molecule of RNA from rice could inhibit a protein that supports removal of low-density lipoprotein, or “bad” cholesterol from the blood. If such a finding proved true for humans, it could have major implications for heart disease and other health issues tied to cholesterol.

It could also have major implications for Monsanto’s new RNAi corn, engineered to silence life-supporting genes in insects.

Opposition was apparent even before Zhang’s study was published. The manuscript was rejected by well-known journals Science, Cell and Molecular Cell. Zhang was eventually contacted by Monsanto’s Chinese office, but in his 2014 interview with Boulder Weekly, he was reluctant to even say Monsanto, often calling it “the company.”

“I just want to say,” he said, “obviously something is going on. It’s not pure science. I just think something is maybe behind them.”

Beyond the politics

In addition to the scientific censorship that occurs in American research on Big Ag technologies, there’s a world of research indicating GMOs and associated pesticides and herbicides aren’t as harmless as federal agencies like the FDA and USDA would lead us to believe.

Much of this research comes from outside the U.S., like the World Health Organization’s (WHO) 2015 announcement that glyphosate, the active ingredient in Roundup, is likely carcinogenic to humans. While studies differ on findings about the link to cancer in humans, the WHO classification came from studies where glyphosate was linked to tumors in rats and mice, and evidence showing DNA damage to human cells from exposure to glyphosate.

And just this month, on Feb. 17, an international group of health scientists published a scientific review on BioMed Health Central calling for investments in studies on glyphosate and human health. They point to studies that find soil and water contaminated with glyphosate, research that found residues of the herbicide in food, as well as analyses examining the damage glyphosate has wreaked on the kidneys and livers of lab rats.

Their review rebuts the biotech industry’s claim that GE crops have led to less pesticide usage, citing available use data published by the USDA, U.S. Geological Survey and the Environmental Protection Agency showing approximately two-thirds of the total volume of glyphosate applied since 1974 has been sprayed in just the last decade.

Such studies confirm that genetically engineered, herbicide-resistant crops have created a culture of single tactic weed management that has placed farmers on an “herbicide treadmill,” using more chemicals than ever as weeds have developed resistance to Roundup. Glysophate-resistant weeds are now covering more than 60 million acres of farmland across the nation, according to a 2013 report from the agrochemical consultant firm Stratus.

In response to this rash of glyphosate-resistant weeds, in January 2014 the USDA approved Dow’s new genetically engineered corn and soybean seeds, designed for resistance against its signature herbicide, 2,4-D. But since glyphosate is the world’s most ubiquitous herbicide, Dow covered their bases. To complement their new seeds, Dow also developed a combination herbicide containing 2,4-D and glyphosate — together they call the seed-herbicide combination the Enlist Weed Control System.

To complicate matters, farmers in the States have the freedom under the label use conditions to mix herbicides in their spray tanks, which could create some lethal combinations with 2,4-D in the mix.

When mixed at a 4-to-1 ratio, Dow’s 2,4-D and picloram pesticides (picloram is sold at most garden centers) create a strong defoliant known as Agent White used during the Vietnam conflict to clear dense jungle. It was the precursor to the infamous Agent Orange defoliant.

Boulder Weekly wrote about Dow’s newest agriculture technology in August 2014 (“Marketshare chemical warfare,” Aug. 7, 2014). In that story, Margot McMillen spoke about how she lost her organic produce — grapes, tomatoes, peppers and potatoes — due to 2,4-D drift from a neighbor’s farm.

McMillen’s issue is a growing problem for farmers in America, conventional and organic. The problem has become so widespread that “chemical trespass” is now a very real crime within the U.S. legal system.

Boulder Attorney Randall Weiner has handled a number of cases dealing with chemical trespass, including a massive loss of crops on the Abbondanza farm in Boulder. Pesticide drift on the organic-certified farm in 2010 cost the owners most of their fall harvest, a $250,000 loss. Weiner notes the Abbondanza farm had land on County Open Space.

He says chemical trespass could become more of a taxpayer liability on County land with expanded use of GMO crops, but it’s hard to know definitively because state and county governments are somewhat protected by the Colorado Governmental Immunity Act.

“It might depend on the lease, what the lease said,” Weiner says. “Someone would need to look at that before there was a contamination incident.”

What about ‘We the people’?

In Boulder County, much of this information and more has been presented to the County Commissioners during the three individual public meetings held earlier this month, and it’s a certainty that more information is yet to come at the hearing on Feb. 29.

But documents obtained through the Colorado Open Records Act by Mary Smith and her husband Scott seem to indicate that public officials shared privileged information about the upcoming Feb. 29 hearing with farm special-interest groups and others who stand to directly benefit from the continuation of the current GMO policies on County Open Space lands, and the information was shared well in advance of public notification of the hearing.

The nearly 300 pages of documents include myriad emails between state and county agriculture employees that show a clear intention to set up private meetings with the Boulder County Commissioners prior to any hearings about GMOs on County land.

Cindy Lair, the state program conservation manager with the Colorado Department of Agriculture, wrote the following to Commissioner of Agriculture Don Brown on Dec. 2, 2015:

“I am forwarding an email from Nancy McIntyre, the District Manager for both districts. Keith Bateman, a Board supervisor from Boulder Valley CD (farms in Louisville, very close to our office), suggested that if we planned a private meeting between you and the County Commissioners it might give them more solid footing as they go into that public hearing in February,” Lair wrote. “There might be challenges with public meetings/sunshine laws to make such a meeting happen, but it may be worth a shot if some support was of offered.”

But Keith Koopman, executive director of the Farmers Alliance for Integrated Resources (FAIR) — the pro-GMO agricultural group formed during the controversial hearings five years ago — sums up the slew of emails best in a Dec. 13 email to Lair in which he calls the anti-GMO activists of Boulder County “green-washed luddites,” and claims that Boulder’s natural foods industry has their “person, Elise Jones, solidly in their pocket.” He also mentions that Jones is the twin of newly appointed City of Boulder Mayor Suzanne Jones and insinuates that the City and County are now working together to stop GMOs on public lands.

His claim that the voice of the natural foods industry in Boulder County is loud may have been true in 2011, but the same doesn’t appear to be as accurate in the lead up to the hearing on Feb. 29. While big name organic brands and natural food purveyors, many headquartered in Boulder County, were featured speakers at the 2011 hearing, those same names can’t be found on current sign up sheets for either the individual meetings or the public hearing. Among those present in 2011 and so far missing in 2016 are WhiteWave/Silk, Hain Celestial, Naturally Boulder, Rudi’s Organic Bakery, Earth Balance/Boulder Brands, Aurora and Revelry.

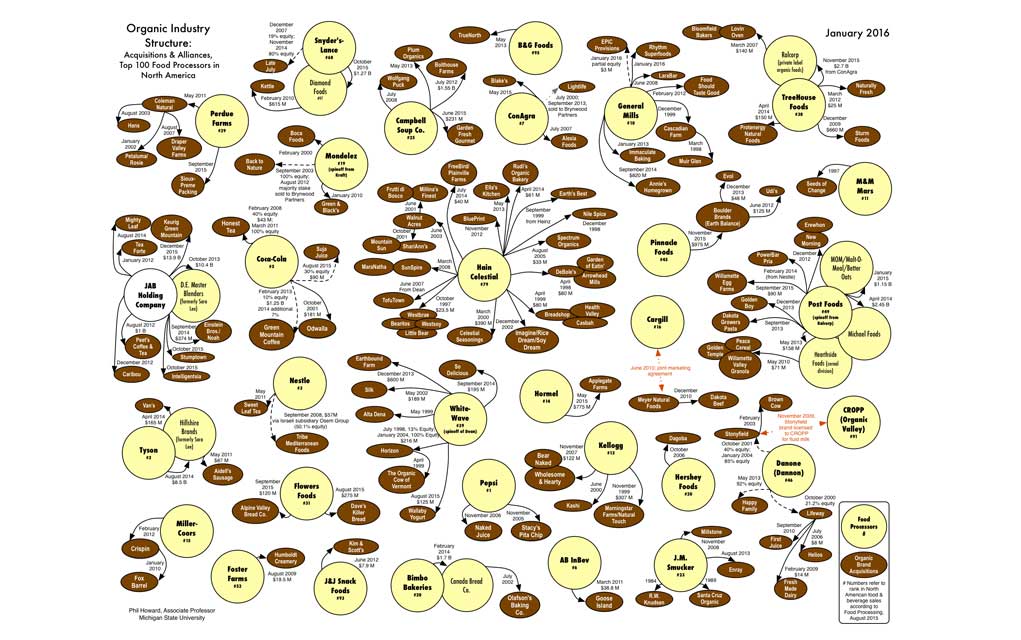

Some within the anti-GMO movement have said this lack of participation from the natural food industry appears to stem from two distinct waves of acquisitions of organic processors by larger food industry conglomerates that use GMOs in many of their other products. The last consolidation wave began in 2012, according to research by Phil Howard, an associate professor in the Department of Community Sustainability at Michigan State (See consolidation map page 17).

During the hearings in 2011, FAIR painted itself as a grassroots organization of farmers who supported using GMOs on Open Space lands. But reporting by Boulder Weekly at the time revealed that FAIR was the brainchild of, and financially supported by, several giant agricultural organizations and corporations. The lines were further blurred when BW discovered that full-page, pro-GMO ads running in the Daily Camera, which stated they had been paid for by FAIR, were actually being paid for by the Colorado Corn Growers Association.

It appears from Koopman’s email in Smith’s CORA documents that FAIR still receives support from Big Ag to spread their message of GMO necessity and safety.

“FAIR [Farmers Alliance for Integrated Resources] has received a couple of grants from the ag. industry (sic) so we have hired a PR firm and have national support from industry representatives to develop a messaging document and campaign to get our voice heard. Social media is a critical part of the project and we are working other more traditional angles as well. We do not intend to drive our tractors off into the sunset just to allow Boulder Brands to enhance their profits and bragging rights for GMO¬free local public lands, all on the backs of local farm families and the stewardship practices on those lands for many years.”

Koopman’s email suggests that Boulder’s organic food industry would prosper even more with a move to zero GMOs on county leased lands. And he is likely correct.

The natural food industry is already one of Boulder County’s largest employers and likewise one of its largest tax generating industries. It has long been argued by those within the natural foods industry that allowing GMOs to be grown on Open Space is a detriment to the Boulder image or brand. If that is true, it is also logical to assume that not allowing GMOs on Open Space would result in even more organic and natural foods companies launching or relocating into the County — the end result of which would translate to far more jobs and more revenue to Boulder County than will ever be realized from leasing Open Space to produce GMO crops, whose largest financial contribution to the County is not having to pay for weed mitigation.

In an unusual and questionable move, the County Commissioners decided not to speak to the media prior to the hearing. Instead, Michelle Krezek, staff deputy to the Boulder County Commissioners, and Public Information Officer Barb Halprin spoke for them.

Halprin says the topic of GMOs on County land is sensitive, even between the three commissioners.

Indeed, Elise Jones and Deb Gardner ran for County Commissioner seats in 2011 on platforms to ban GMOs on County Open Space Land. Cindy Domenico, on the other hand, voted to extend and expand GMOs on county land as a commissioner in 2011.

Back then, Domenico lamented the multitude of “all-or-nothing demands” from the public, something Halprin says the commissioners have seen from the current round of public meetings as well.

“Are there other ideas? Are there actual ways that people could come forward and say, ‘We understand this can’t be ended over night but here’s a thoughtful way to start moving in that direction’?” Halprin says. “That’s the kind of input the commissioners would like to see. They are seeing a lot of ‘Don’t’ make any changes’ or ‘Ban them outright.’ Not a lot of middle ground here.”

When asked about the timing of the public hearing — to be held in late February when the policy doesn’t expire until December — Krezek says it was scheduled early to give farmers time to plan “in response to any change with that policy.”

She notes that a final decision doesn’t have to be made on March 17. Commissioners can ask for more studies or allow more public hearings.

However, with spring planting so close, County Agriculture Resource Manager David Bell says it would be a “challenge” to implement any changes to the Cropland Policy this season.

But there’s one change to the Cropland Policy that Boulder County wouldn’t be able to make no matter how much time passes — a return to commercial scale non-GMO sugar beets.

In 2008, Monsanto released its Roundup Ready sugar beet, and by 2010, the GM sugar beets comprised 95 percent of the total U.S. sugar beet market. The Center for Food Safety filed a lawsuit claiming that the USDA had violated the law by licensing Monsanto’s genetically engineered sugar beets without performing the required environmental impact study. Ultimately, a federal judge ruled in favor of the Center and ordered Monsanto to pull the product until a study could be done and released.

But the product was never pulled.

As a result of Monsanto’s massive monopoly over the sugar beet seed industry, the FDA told the judge that if followed, his order would cause a sugar shortage in the U.S. because there weren’t enough non-GMO seeds left to replant.

It was a perfect illustration of Monsanto’s business model. Put out GE seeds, conquer the entire market within 24 months, buy up the remaining stocks of non-GMO seeds so they are not available. And by the time negative research or the courts come along and try to stop it, it’s already past the point of no return, so the government — which has been heavily influenced by Monsanto’s massive lobbying and campaign finance expenditures — simply says, “Well then, carry on.”

Bell, the county agriculture resource manager, confirms simply that, “No, it’s not a possibility” to grow non-GM sugar beets at a commercial scale.

“Do they exist? You can buy a small package, a set up for people trying to do a homestead,” he says. “We have found them, but not more than 20-seed packets.”

• • • •

So there you have it. This is just a fraction of what we’ve learned about genetically modified organisms and associated herbicides and pesticides since the last time the Boulder County Commissioners tangled with the topic of GMOs on County Open Space.

So what can we expect to happen this time around? Will the two Commissioners who campaigned on the promise to eliminate GMOs from county open space keep their promises. If so, they have the votes to make it happen.

Or, will they, as the Commissioner’s surrogates to the media seem to be foreshadowing, look instead for some middle ground compromise that will allow GMOs on Open Space while giving them cover for going back on their campaign promise?

A lot may depend on who shows up and what is said at the upcoming Feb. 29 public hearing, which will be held in Longmont in the same room at the Convention Center where the meetings five years ago took place. We know that FAIR and its statewide network of Big Ag will turn out a room full of green-hat wearing farmers, mostly from other counties in the state. So the question is, with the lessened support from Boulder County’s increasingly consolidated natural foods industry, who will be there to speak for the other side? Guess we’ll all have to turn out on the 29th to find out.