During his first few days in office, President Biden set out to promote equity in federal climate action with the stroke of a pen. The signing of Executive Order 14008 created the Justice40 Initiative, mandating 40% of climate-related investments from certain federal agencies flow to communities identified as underserved and overburdened by pollution.

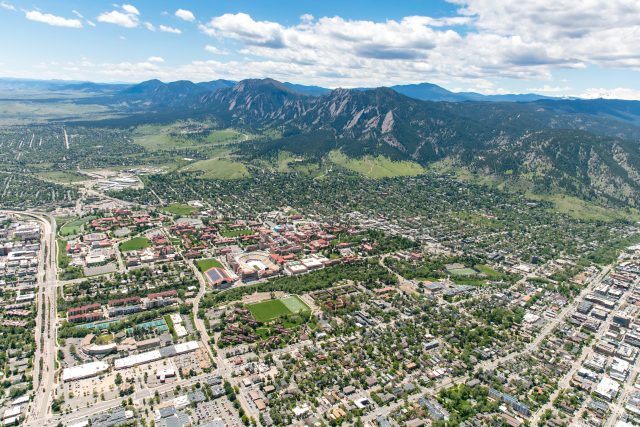

While 263 census tracts in Colorado — three in Boulder County — qualify as disadvantaged, many communities have yet to see the benefits of Justice40, leaving leaders to grapple with how to ensure the money gets to those who need it most.

“This is something that in the next year and a half is going to be delivering hundreds of billions of dollars, and our communities need to be kept up on that so that the federal government money is invested in the communities that it was intended for, those that have been most disproportionately affected for the last 50 years,” says GreenLatinos President Mark Magaña, who lives in Boulder and is part of a Justice40 collective that provided recommendations to the federal government.

Brett Fleishman, who stepped into his current role as senior climate strategist at Boulder County’s Office of Sustainability, Climate Action and Resilience in 2021, says his first big task was figuring out the county’s strategy “to the single largest investment the federal government has ever placed in climate action.”

The county has applied for several grants that would be covered by Justice40, including a project to add more electric vehicle charging stations across the county and another that would invest in increasing the urban tree canopy to reduce heat. Each is a multi-million dollar grant that will be awarded to recipients in the fall.

Money moves slowly though the federal government, Fleishman says, but he expects 2024 to be a big year for Justice40-covered funding coming through the Inflation Reduction Act.

“Justice40 is vague, it’s frustrating, it’s slow,” Fleishman says. “But it’s a really smart policy, because all the local governments are forced into the process.”

Boulder County is part of a regional coalition on the Front Range that was awarded $3 million to be distributed this summer as part of the Climate Pollution Reduction Grant program. The initiative is designed to help states, local governments, tribes and territories develop strategies to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and other air pollution.

But since the Justice40 initiative was created via presidential fiat, there’s fear a new administration could reverse the order if Biden loses his reelection attempt in 2024.

“We think the Biden administration [and] federal agencies are moving quickly to establish things and get money out the door, because once it’s out the door, you can’t claw it back,” Fleishman says. “But if they take too long to set up the programs and there’s an administration change, then those programs are vulnerable.”

‘Mitigation is a luxury’

Some Justice40 money has already flowed into the Colorado. Using more than $32 million from the Department of Energy, Colorado School of Mines (Golden) and Carbon America (Arvada) will collaborate with New Mexico-based Los Alamos National Laboratory to explore the feasibility of a carbon storage site in Pueblo.

The funding covers the first phase of the project, which includes data collection, planning, site characterization and analyzing potential social and environmental risks.

“Whatever we do will be done with an eye toward environmental justice, to social justice, to equity,” says Manika Prasad, who is leading the project and is director of the Mines Carbon Capture, Utilization and Storage Innovation Center. In the early portion of this project, this means training on equitable hiring practices and hosting town halls in the community.

If the site is feasible, it would be able to store 50 million tons of CO2 over 30 years.

“Mitigation is a luxury that more affluent societies have,” Prasad says. “We’re coming in to say, ‘No, mitigation needs to be where the problem is, not where the money is.”

Justice40’s screening tool identifies disadvantaged communities using factors like legacy pollution, wastewater discharge and energy costs coupled with low-income by census tract. Fleishman says that system has its flaws, and the county hopes to use a more comprehensive and granular list of indicators.

“Sometimes a mobile home community is in the same census block group as a wealthy community, and when you put those two together, that census block group doesn’t look like the Justice40 block group,” he says. “The wealthy homes just wash out the statistics.”

Race is not used as an indicator in the screening tool, likely because the administration believes they wouldn’t stand up to a Supreme Court challenge. “They try to use other things that oftentimes will be an overlay of racial disproportionate effects, like income or housing density,” Magaña says.

Boulder County Commissioner Marta Loachamin says a successful Justice40 investment will require bringing people of color to the table and moving past the planning phase of projects.

“We’ve been asking, and we’ve been telling, and we’ve been sharing, and we’ve been in focus groups, and we’ve been studied, and we’ve been researched,” she says. “We have an opportunity with Justice40 to bring folks of color and organizations who are led by folks of color to truly create this plan and to implement the work.”

‘We’ve had enough trickle down’

While the executive order only mandates 40% of investments benefit disadvantaged communities, Magaña says the funds need to be invested directly into those communities.

“I’m hoping they still do an investment analysis,” he says. “Not just, ‘How did the benefits trickle down to this community?’ We’ve had enough trickle down.”

Magaña says many small organizations and communities may be unaware of Justice40, or may be intimidated by long, cumbersome grant applications.

“It’s a heavy lift to be able to go from a one-, two-, three-person under-resourced organization to one that’s going to be a primary applicant for federal government funding,” Magaña says. “We wanted to make sure government entities knew that communities of color needed significant technical assistance to really even participate in federal grants, let alone be the primary applicants.”

It starts, Magaña says, with education about Justice40 and what qualifies. Then, communities need access to technical assistance and matchmaking opportunities for larger organizations that have experience with federal funding to partner “with groups that really have the specialty to do the on-the-ground work.”

As climate change intensifies, Fleishman says equity is more urgent than ever.

“The poor and marginalized always sort of carry the brunt of most crises,” he says. “This is a moment for us to absorb this tool and make it part of what we do and part of government so that when things get harder, it’s like muscle memory.”