The talk around Boulder for the past few years, among young and old, from every socioeconomic background, hippies to businessmen, has been largely about one thing: weed. Since medical dispensaries became a reality, the general public has learned a lot about weed and its myriad subgroups: Island Lady, Chronic Supernova, Red Hair, Durban Poison.

There is, however, another weed that almost no one is talking about. Most don’t know it exists, and couldn’t recognize it if it were growing in their own flowerbeds, open space or even in their meticulously maintained, xeriscaped yard. It too has a lot of names. Some call it non-native. Others refer to it as noxious. But probably the best name for it is invasive.

And unlike the weed people all over the world smoke for pleasure, pain relief or combating anxiety, this weed is dangerous and harmful. It kills nearly everything it touches.

To say invasive weeds are a problem in Boulder County is a gross understatement. They are everywhere and include so many varieties it’s hard to keep them all straight. There’s diffuse, spotted and Russian knapweed; leafy spurge; musk, Canadian, Scotch and bull thistle; as well as yellow and Dalmatian toadflax.

And that’s just a small list of some of the easy-to-spot weeds playing havoc with the natural balance of Boulder County’s disparate ecosystems. Most look normal, like something you’d see every day walking the dog or hiking across open space. They hide among native plants, slowly killing off competitors in the area until they are all that remains. Most are so well adapted to the temperature, arid climate and hard-packed soil of the high-plains desert that nothing but the most vigilant strategy will ever rid the area of the scourge.

And they are opportunistic, taking advantage of even the most devastating situations — like the recent Fourmile Fire — to further their stranglehold on nature.

An initial assessment by the Fourmile Emergency Stabilization (FES) Team, a multi-agency group made up of natural resource specialists and experts from the Boulder County Departments of Parks and Open Space, Transportation, Land Use and Public

Russian olive tree

Health, as well as the Bureau of Land Management, U.S. Forest Service, Natural Resources Conservation Service, CSU Extension Services and Colorado State Forest Service, shows there is high potential for noxious weeds to encroach on the burned area and compromise the establishment of native species. The FES team has recommended emergency stabilization of the area through aerial mulching, seeding, treating known noxious weed infestations, and monitoring for new weed infestations.

That battle against non-native weeds is fought every day right under the nose of a mostly uninformed public by people like Steve Sauer, weed coordinator for Boulder County Parks and Open Space.

“We’re making progress,” says Sauer.

“I think it’s a war that … on some weeds it’s winnable. On others it’s more of a control situation.”

In 2004, the state of Colorado set up a program to list all the invasive weeds it could find and categorize them according to how strong a stranglehold they have. “List A” weeds are those in low enough numbers that they can be irradiated, according to Sauer. “List B” weeds are those the state, county and cities can control, though ridding the area of them is unlikely.

The last category, “List C,” is reserved for those weeds that no amount of perseverance will affect. The state has no plan for eradicating these plants or for stopping their spread. “List C” contains a little more than a dozen plants with harmless-sounding names like chicory, downy brome and velvetleaf. There’s also something called puncturevine, which is just as nasty as it sounds, as well as poison hemlock, which is sometimes mistaken for parsley or carrots and can kill a full-grown horse in as little as five hours.

Where the fight is winnable, Sauer says the county is doing all it can with limited resources to claim victory.

“We’re seeing less and less every year,” says Sauer of the List A weeds. “We’ve worked with the city of Boulder and the Department of Commerce to do volunteer weed pulls over the last several years. We get about 100 people in the first week of May.”

On open space the county employs a group of volunteer weed monitors who hike trails and identify weeds. Sauer says they also get calls from everyday people who see weeds that don’t look right and report them to the county.

That, says Sauer, is the best tool the public has to assist the county in its weed battle.

“They can be educated, know exactly what kinds of weeds they have, know how to control them and be willing to control them,” says Sauer of the public.

Sauer says Parks and Open Space partners with Boulder County Land Use to work with private landowners to make them aware of the weeds they have and just how dangerous they can be to native plants on their land.

Parks and Open Space also distributes brochures, weed calendars and

partners with the Colorado State University Extension to put on

small-acreage management classes to help people learn to identify and

treat weeds. It all helps. But the battle is far from over, and the

enemy never sleeps.

From whence they came

Weeds

are everywhere, but in most cases weeds from here are better than weeds

from there. Just like any organism that finds its way to a place where

conditions are right for it to not just survive but thrive, weeds tend

to die off in places unsuited to their particular evolutionary bag of

tricks, and thrive when conditions are more accommodating. For a handful

of invasive weeds, Boulder County is the perfect place to settle down

and start a family.

But how did they get here in the first place? In most cases people, as usual, are the problem, and not just reckless people.

Laurie

Deiter, one of the City of Boulder’s integrated pest management

coordinators, says many of the 33 species of plant she now struggles to

eliminate were introduced to Boulder County as an attempt to develop

richer pasturelands or fix other problems facing land management

officials decades ago. One such problem was forest fire damage. In the

1970s, forest fires did extensive damage to the mountain backdrop of

Boulder County. Blackened hillsides replaced the lush, green forests,

and officials at the time felt getting the color back was the least they

could do. Thus began Project Greenslopes, a plan to reclaim the

flame-ravaged land. It worked, but the plants of choice were

fast-growing, non-native grasses.

“People

didn’t think of what [these grasses] were going to do to that habitat,”

says Deiter. “[Forty] years later they are still wreaking havoc.”

Other

invasives were brought into the area by equally well-meaning people

looking for a drought-resistant solution to landscaping.

“A lot of these weeds are escaped ornamentals,” says Sauer. “Myrtle spurge was used as a xeriscape plant and escaped.”

Ornamental

trees, too, have become an enormous problem, according to Sauer, Deiter

and just about everyone in the noxious weed-fighting business.

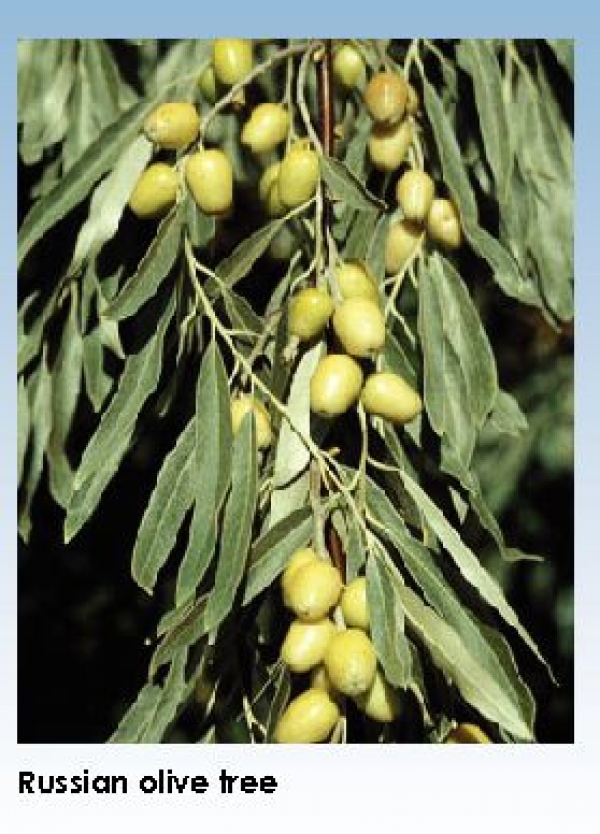

“Russian olives creep in and run out cottonwoods,” says Deiter.

Sauer says it often causes friction with the public when they see someone cutting down a beautiful, perfectly healthy Russian olive.

“It’s hard for people to understand why we cut them down,” says Sauer. “We’ve gotten rid of thousands of them.”

Pretty

or not, Russian olives do more damage to the environment than one would

think. The tree is classified as a List B weed that grows mostly in

riparian areas, places that are already under strain. And what they find

there, they exploit like no other weed.

“They take a lot of water,” says Sauer. “Some say they can use 200 gallons of water a day.”

This immense thirst causes big problems for plants and trees in the area.

Russian

olives crowd out willows and cottonwoods, says Sauer, by spreading out

their roots and sucking up all the available water.

But the problem is larger than that, according to Deiter.

“Cottonwoods hold dozens of insects that migratory birds feed on,” she says.

With

the cottonwoods disappearing, replaced by Russian olives, which harbor

no insects of interest to birds, birds no longer find the food they need

to make their long flight south in the winter. The problem is so

widespread, according to Deiter, that migratory patterns have actually

been disrupted due to the lack of food.

It

can be difficult to pin down just how other invasives got here,

although most agree they came over sometime in the 19th century.

“A

lot of our weeds came from Eurasia,” says Sauer. “They either were

spread by birds or came over in hay. They might have been pumped out of

the bilge of ships — who knows. But they’ve been here a long time.”

Fighting the good fight

How invasive weeds got to Boulder County is an interesting question, but it has nothing to do with solving the problem.

Getting

rid of non-native plants is a complicated task that strains resources

and continually tests the creativity and tenacity of weed managers.

“The

poor weed managers are under a lot of pressure from the public,” says

Tim Seastedt, a University of Colorado at Boulder ecology professor.

“I’m sympathetic.”

Seastedt

has been looking for ways to rid Boulder County of one of its most

pervasive invasive plants, knapweed. Ten years ago, Seastedt began a

test of biocontrol eradication, which essentially means using another

organism to kill the undesirable plants. In this case, Seastedt chose

two different bugs — the seed head weevil and the root weevil — to go to

war with knapweed. The experiment, which took place on open space land

south of Superior, showed promising results.

“We

released the insects in the late ’90s,” says Seastedt. “Other sites

nearby have much more knapweed. The [test] site has stayed [relatively]

knapweedfree, but less and less as time goes on.”

The

reason the knapweed hasn’t been completely killed off by the bugs,

according to Seastedt, is a native species that has fought its own

battle for survival in the area.

“Since then the site has been invaded by prairie dogs,” says Seastedt. “On disturbed sites more knapweed comes up.”

The

problem is actually a mixture of things. Knapweed produces lots of

seeds, which generally don’t grow. But they do stay viable for a long

time, laying on the surface waiting for an opportunity to get planted in the ground.

“The knapweed had a decade of seed production head start,” says Seastedt.

When

prairie dogs moved in, they essentially tilled the soil by digging

their burrows, helping the massive collection of seeds to finally plant

themselves. The result is an increasing knapweed population, being

fought by an ever-shrinking number of weevils.

“We’ve

been monitoring [the situation],” says Seastedt. “The bugs don’t

disappear when the plants drop down. They drop down, as well.”

What

the bugs need to make a real, ongoing dent in the knapweed population

is an ally — a native plant to help push the knapweed out.

“Insects

do the best job in conjunction with plant competition,” says Seastedt.

“Bugs need plant competition to work well. The whole goal of killing

weeds is replacing it with something you want. That’s been the big

difficulty.”

Other

factors help the bugs, as well. “We’ve found with biocontrol it really

helps the insects if there is something going on to help them,” says

Sauer. “If there’s a drought, that helps.”

Pay to spray

Another

big problem with weed management is the use of herbicides, chemicals

that kill either select plants or every plant they touch. The issue with

the chemicals, aside from their questionable usefulness, is the danger

many people say they pose to the public. Betty Ball, a long-time member

of the Rocky Mountain Peace and Justice Center, has led the charge

against herbicide spraying in Boulder.

“The

weeds won’t hurt you, but the toxics will,” says Ball. “The period of

toxicity that’s on labels is nowhere near accurate. When you do research

you find the toxicity lasts much longer than what is reported.”

Ball

says the city and county put too much emphasis on chemicals for weed

eradication, and even questions the need for eradication at all. She

cites a study by Kathy Voth, owner of a company called Livestock For

Landscapes (www. livestrockforlandscapes.com), that shows animals could

be the best alternative to spraying.

“They found that in a pasture where there were a combination of weeds and grasses, the cows prefer the weeds,” says Ball.

Voth’s

website lists sites where cows have been used, to great effect, to keep

weeds at bay. One of the highlighted cases is a Boulder County Parks

and Open Space program called “We’d Eat It!,” which ran from 2007 to 2008.

“The

county’s Small Grant program funded this project to teach cows to eat

late-season diffuse knapweed,” the site reads. “Cows began eating the

weed on the afternoon of the fourth day of training and grazed it in a

2.11-acre test pasture and a 40-acre pasture. In 2008, we followed up as

cows trained their calves to eat diffuse knapweed. We trained them all

to eat Dalmatian toadflax, and they chose on their own to add Canada and

musk thistle to their diets.”

Although

he says the county still uses herbicides in some cases to kill weeds,

Sauer adds that the chemical component of the weed management plan,

primarily a herbicide called Milestone, is becoming smaller and smaller

as time goes by.

“We

can put on less chemicals than some of the ones we’ve used in the

past,” says Sauer. “And we only spot spray. If we see a spot with weeds,

we spray that.”

Clearly

the efforts of the Peace and Justice Center and other anti-chemical

activists have worked to some extent. Seastedt says outside pressure has

played a huge role in the change.

“Right

now I think broadcast spraying would be viewed badly,” says Seastedt.

“It does more damage to nature than to the target weeds.”

Susan Richstone, the city of Boulder’s comprehensive planning division manager, agrees.

“It’s

so important to our community that we be on the leading edge,” she

says. “We really use very little in the way of [herbicides] on city

properties.”

Sauer agrees the trend is moving away from herbicides.

“You

have to know when to [use herbicides],” says Sauer. “We use mechanical

control (pulling weeds by hand or digging them up) and cultural control

(releasing insects).”

Despite

the progress the city and county have made in reducing the amount of

chemicals they use, any amount is too much for Ball.

“We

already have an incredible body burden from other chemicals in the

environment,” says Ball. “They have linked ADD, Parkinson’s and breast

cancer to the overuse of pesticides and herbicides. They go and spray

the playgrounds where kids are going to play.

What can kids do? They play on the ground.”

Alice

Guthrie, recreation superintendent for the City of Boulder Parks and

Recreation Department, says playgrounds are no longer sprayed for weeds.

“Our

practice now is to only do manual control in playgrounds,” says

Guthrie. “When we did the review several years ago, that was one of the

changes we made.”

Richstone says Boulder’s Open Space and Mountain Parks does no spraying whatsoever.

The

county’s Parks and Open Space department does spray, according to

Sauer, but works hard to notify the public when and where it plans to

use chemicals.

“We’re pretty careful because it is a big deal,” says Sauer.

The

county has established a weed hotline so residents can call to find out

where chemicals will be applied. The county also puts out a monthly

notice listing areas designated for spraying and places signs in those

areas to warn the public.

Beyond

that, Sauer says, the state has a pesticide-sensitivity registry the

county uses to notify residents near spraying areas before any chemicals

are applied.

Richstone

adds the city takes its weed control policies and the tools it uses

seriously — so seriously that it has decided to seek an independent

review of its programs and practices.

“It’s

been a number of years since [the weed management plan] was put in

place,” says Richstone. “There’s been a lot happening in the field.

Let’s look at what other communities similar to ours are doing and make

sure we’re using best practices. I’m sure we will learn something in the

process.”

Richstone

says the city council has authorized $50,000 to hire a consortium of

three integrated pest management consulting companies: Integrated Pest

Management Institute of North America, Pesticide Research Institute and

Osborne Organics.

The money will also pay for whatever changes in policy are recommended.

The report, Richstone says, will be done in time for a public review early next year.

“We

want to know what we’re planning to do for the next season, so we

really do need it by early next year,” says Richstone. “We might get one

step better or identify areas where we might need to grow.”

The public’s piece of the puzzle

While the city and

county are vigilant about keeping public lands free of invasive weeds,

there’s little they can do about private property, especially gardens

where some people unknowingly cultivate problem plants.

Sauer says the best thing citizens can do is to learn what constitutes a noxious weed.

“They

can get educated,” says Sauer, “know exactly what kinds of weeds they

have, know how to control them and be willing to control them.”

Mikl Brawner, co-owner of Boulder’s Harlequin’s Gardens, says there are safe, organic options for keeping your lawn weed-free.

“The

alternative to weed and feed is corn gluten,” says Brawner. “Put it on

in February and September, and it keeps the weed seeds from emerging.”

In

addition to keeping the home front clear of weeds, Sauer says there are

plenty of opportunities to lend a hand on public lands, as well.

“We’ve

got volunteer groups, monitors that hike trails and identify weeds and

let us know where they are,” says Sauer. “If people are hiking on open

space and see a weed, just call us and tell us. That would be great.”

RESOURCES

State pesticide sensitivity registry: http://tinyurl.com/2fjfx5y

Boulder County weed hotline: 303-441-3940

City of Boulder weed management website: http://tinyurl.com/2fq6g3l

Boulder County weed management plan: http://tinyurl.com/2fq6g3l

Colorado noxious weed list: http://tinyurl.com/2e9np79

Respond: [email protected]