Long gone are the days when people in the United States would ask me where I’m from, and when I’d say Venezuela, they’d reply: Minnesota? Doing my best not to roll my eyes, I would take a deep breath, smile and say, “V-E-N-E-Z-U-E-L-A.”

Nowadays, my country is making headlines across the American media landscape, and its future is at the top of the Trump administration’s agenda. Now when I say I’m from Venezuela, people ask: “Do you still have family there? How are they?”

I do have family and friends back home, and I go back several times a year. I have witnessed, firsthand, how my country has plummeted into deep crisis. I have seen friends lose weight because they can no longer afford three meals a day. I have seen people dressed in executive-office clothes in the streets of Caracas, looking for food in the garbage. I have walked in slums where there hasn’t been running water in years. The list goes on. Because the U.S. is now deeply involved in my country, I feel the need to explain what is happening in Venezuela and how we got to this point.

Nicolás Maduro was elected president in 2013 after Hugo Chávez died from cancer. I was working as a reporter at Venevision at the time, and it was beyond hectic. In October 2012 Chávez had defeated Henrique Capriles Radonski — the opposition leader. With Chávez’ death, we only had six months to prepare for a new presidential election. We were caught off guard. We all knew President Chávez was sick, but he was adamant that he was cured and ready for another term. In six months we went from covering a presidential election to covering a funeral, to another presidential election. In April 2013, Maduro won a hotly contested victory by less than two percentage points over Capriles.

Maduro’s administration was doomed from the beginning. The opposition leaders and their supporters started calling him “The illegitimate one,” claiming the margin of victory too small, the election biased and pointing out that Maduro’s campaign had many advantages compared to Capriles’. For example, Maduro had money from PDVSA, the national oil company, and the state, which he used to organize meetings and pay off voters.

Even as he took office, the weight of funding his predecessor’s popular social programs, “Misiones,” which include low-income free housing, subsidized food and nearly free medicine, quickly became a massive drain on the economy. Alongside widespread corruption and low oil prices, these social programs drove Venezuela into a spiral of hyperinflation, extreme poverty and food and medicine shortages.

In 2014, mass protests and sometimes dangerous street barricades, known as “guarimbas” sprang up all over the country. In 2015, an opposition unified party, known as MUD, won two-thirds of the parliament. But in 2017, Maduro found a way to diminish the opposition’s power by creating a new legislative body called the Constituent Assembly, taking all power from the rightful democratically elected National Assembly.

Maduro pushed this takeover through at the time by claiming that his new “assembly” would be the solution to the economic crisis and violence that had gripped the country.

The creation of Maduro’s Constituent Assembly did not bring prosperity nor peace. As the days went by, the crisis deepened, consumer goods became more scarce, and millions of Venezuelans started fleeing the country, causing an unprecedented migration crisis in Latin America.

Amid the turmoil of this political, economic and humanitarian crisis, presidential elections were held in May 2018. They were completely different from the previous two I’d covered. Driving all over Caracas, I noticed that there were no lines at the voting centers as there had been in the past. The lack of turnout was palpable. Maduro won, but the opposition and international observers alleged that the election results were illegitimate and that Maduro was simply giving a democratic façade to what was now his dictatorship.

The 2018 elections are the reason more than 60 countries today do not recognize Nicolás Maduro as president of Venezuela. Instead, they recognize Juan Guaidó, a 35-year-old politician who came out of nowhere and took Venezuela and the world by surprise.

Guaidó started his political career mentored by the opposition leader Leopoldo Lopez, who has been under arrest the last five years. As a member of Lopez’s Voluntad Popular party, Guaidó won a seat in the National Assembly in 2015. In January 2019, Guaió was sworn in as President of the National Assembly of Venezuela, just a few days before Maduro was sworn in for his second term.

On Jan. 23, Guaidó proclaimed himself the interim president of Venezuela asserting that Maduro’s election was fraudulent and had left the country without a legitimate president. Guaidó based his claim in Article 233 of the Constitution of Venezuela that states that if the president-elect is absent, the president of the National Assembly must take office until new elections are held.

The international media’s penchant for using the term “self-proclaimed” when describing Guaidó has brought a good deal of criticism from him and even his supporters as they all believe Guaidó is following the Constitution.

Right after his proclamation, the Trump administration backed Guaidó’s claim, recognizing him as the true president while imposing more sanctions on the Maduro regime and PDVSA.

More than 60 countries followed the lead of the U.S., while Maduro scrambled to secure the support of Cuba, Bolivia, Iran, Mexico, Russia, Uruguay and China. While some other countries have remained “neutral” like Italy, they are still calling for new elections to end the crisis.

Many of my friends back home and Venezuelans around the world see President Trump, John Bolton, Mike Pence, Elliott Abrams, Mike Pompeo and Senator Marco Rubio as heroes — the only hope for solving the crisis. It’s not unusual when reading the comments of any of these U.S. politicos on social media posts about Venezuela, to see thousands of thank you messages and people begging for a U.S. military intervention.

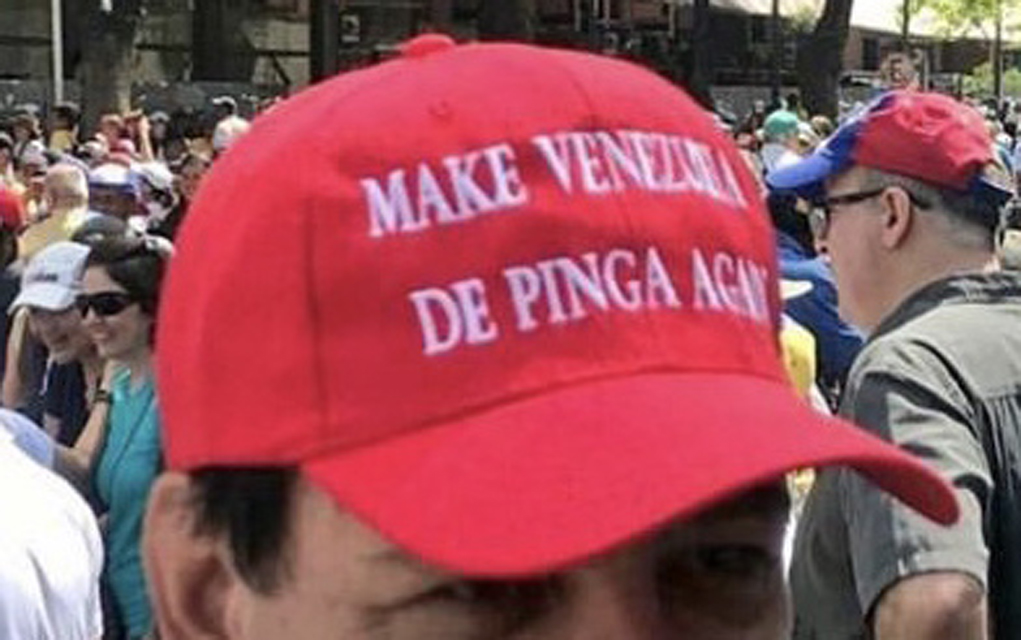

At the protests against Maduro taking place in my country, it’s common to see people displaying banners in support of the Trump administration and wearing hats with the quote “Make Venezuela D’pinga again” emulating the well-known MAGA hats. “D’pinga” is Venezuelan slang for “awesome.”

There is a joke about the next popular baby names that will be showing up in Venezuela. For years, many Venezuelans have named their children inspired by American pop-culture. For example, there is a Venezuelan woman named “Disneylandia.” There’s a “Maikel Jordan” and several “Usnavys” after a U.S Navy ship was seen at the coasts of Maracaibo City many years ago. So now, with the level of popularity of members of the Trump administration, the bets are that “Donaltrun,” “Maikepence,” “Marcorubio” and “Jonbolton” will be pretty popular in the near future.

Guaidó, with strong support from the international community and perhaps the vast majority of all Venezuelans, is insisting that the army let humanitarian aid enter the country to help ease the deadly crisis.

But his main political agenda has three specific demands, not counting accepting humanitarian aid. First, he’s demanding Maduro resign; second, he wants the installation of a transitional government led by him in accordance with the Constitution; and finally, he’s calling for free, democratic elections. Easier said than done.

For Guaidó’s plan to be successful, he needs Maduro to either voluntarily cede power or secure the support of the Venezuelan military. So far, the military is siding with Maduro, even though many members and some leaders have switched their allegiance to Guaidó. Still, there is always the option of foreign military intervention.

The Trump administration has repeatedly said that all options are on the table to solve the Venezuelan crisis. After what happened on Saturday, Feb. 23, this intervention scenario seems increasingly more plausible.

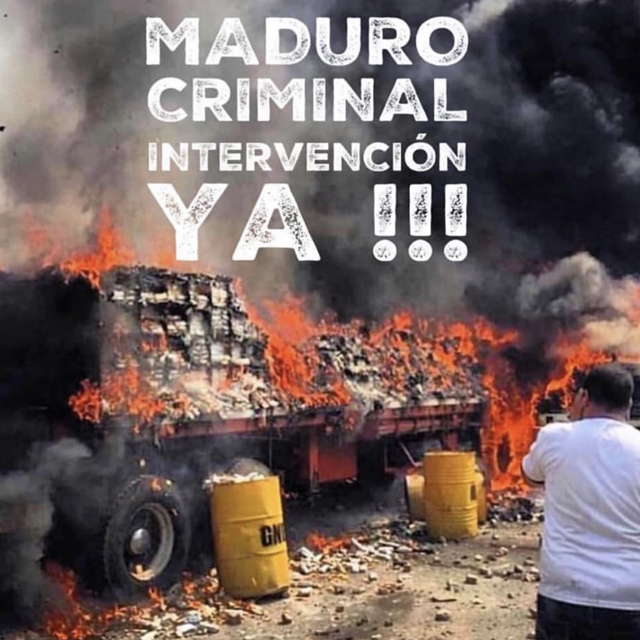

As that Saturday approached, I could not sleep. I found myself checking the news constantly. Feb. 23 was billed as the day when the humanitarian aid sent by the nations supporting Guaidó was going to enter Venezuela, through the borders of Brazil and Colombia. Instead, it ended with trucks full of aid supplies on fire, riots, injuries and blood in the streets.

In the aftermath of Maduro’s forces refusing to allow the aid to enter, Marco Rubio tweeted a condemnation of the events and hinted at the possibility of a military response: “The whole world saw the regime use security forces and gangs to injure and kill unarmed civilians. The whole world saw them set fire to three trucks carrying food and other humanitarian aid. They will soon realize just how badly they overplayed their hand today.”

Guaidó, speaking from Colombia in response to the violent events on the border, called for a meeting on Feb. 25 with the international community, because he felt “obligated” to keep “all options open to liberate the country,” he said.

Maduro supporters claimed that it was violent groups paid by the opposition who set aid trucks on fire and acted violently in an effort to give the U.S. military an excuse for intervention. According to Maduro, an intervention could spark a civil war in Venezuela.

Throughout February, the tension grew day by day. Guaidó and his supporters urged the military to let the aid inside the country. Maduro maintained his orders that the army continue to keep the border closed, claiming that the humanitarian aid was just an excuse and prelude to military intervention. The Maduro administration has gone so far as to claim Venezuela is not undergoing a humanitarian crisis, even though at the same time it is accepting medicines from Russia to ease the crisis that it says does not exist. In the past few months, Maduro has not asked for and has rejected offers of humanitarian relief by the Red Cross and the United Nations.

During the violent events of Feb. 23, friends and family group chats and social media exploded with messages of concern. It is getting worse every day. Venezuelans inside and outside the country are hooked to our phones, checking the social media profiles of key players on the crisis and journalists who are covering the events. For many years, such social media has been the only way of getting accurate information inside the country, because the government severely censors broadcast and print media.

Points of view can get so polarized that taking a stand can alienate you from friends and family, despite being in the same “boat.” For instance, in my friends and family chat groups, it gets heated when someone says, “Oh I don’t trust Trump,” or, “I don’t want a military intervention.”

People in the U.S. who have strong anti-Trump feelings or socialist-left political views tend not to support any intervention in Venezuela’s internal issues and some even believe that the crisis is due to the U.S.-imposed sanctions. But then you have millions of Venezuelans applauding everything the Trump administration does.

There are many half-jokes on social media that Venezuelans will come build the wall for free if Trump manages to overthrow Maduro. After the border clashes, thousands of Venezuelans messaged Rubio and members of the Trump administration through social media asking for immediate intervention to overthrow Maduro.

But despite all of these extreme differences of opinion, there is a reality that is simply the truth: Venezuela needs a change, the crisis needs to be addressed. People are dying. It has to stop, and this is why:

Hyperinflation in Venezuela is just impossible to understand. The rate stands at 27,364 percent. The prices change so much every hour that even though I was born and raised there, on my most recent trip home last December, I could not keep up. I had to constantly ask how many American dollars any amount was. Also, credit cards cannot keep up with the hyperinflation. To pay for dinner in a fancy place you might need several cards with the maximum limit just to afford one meal.

Venezuelans who have access to American bank accounts are constantly exchanging dollars in the black market to fight hyperinflation. When my uncle died three months ago, my family went immediately to get a quote from the funeral home. They then asked me, living in the U.S. to exchange dollars to bolivars in order to pay the fee, but I was busy at the time and it took me about four hours do it. When they went to pay, the funeral home told them the price had already gone up by 15 percent in only four hours. So, I had to exchange the extra, quickly, because first, they wouldn’t take the body of my uncle without full payment even though it was literally lying right outside. And second, because the fee would just keep getting higher by the hour.

More than 80 percent of Venezuelans live in poverty. With the minimum wage in Venezuela, you would only be able to afford a beer in the U.S. once a month and nothing else. Venezuelans make $6.13 per month on average. With hyperinflation and the abrupt rise in prices, that’s nothing. When people back home go buy groceries, they can barely afford a dozen eggs.

Because of this, the government subsidizes food with a program called CLAP that gives people a small bag of food per month that has to be rationed to make it last. It takes many long hours in line to get a bag. The food shortage has caused more than 50 percent of Venezuelans to lose an average of 25 pounds, in what is now known as the “Maduro Diet.”

And hell, I have seen many of my acquaintances and friends just shed weight away. On my last visit to Caracas — last Christmas — I saw a friend I hadn’t seen in a couple of years, and complemented her on how slim she was looking. She said, yes, “Maduro’s diet.” At first, I thought she was joking, but then I was hit with the reality that this middle-class professional woman could not afford three meals per day.

It has gotten so bad that tips are given in food. With the currency worth almost nothing, you have to literally wire money to give someone a meaningful tip: It’s more common now for people to go out with pieces of cake or bananas to give away as tips.

Living in such a depressing environment has made Venezuelans look for better, more creative ways to help feed the vast majority of the country. People will cook whenever they can, as many as 50-60 meals, and drive around cities to give away plates of food.

Medicines are scarce. Venezuelans need to go to the black market or social media to look for medicines. For example, not a day goes by that I don’t see friends looking for medicines in my social media feed. And the most outrageous thing is that people are swapping goods, like trading antibiotics for flour or toilet paper.

In hospitals, it is not only medicines that are missing, but water, electricity and essential services. A walk past any public hospital is a heartbreaking scene. It makes you feel like there is no hope in the world. My cousin is a surgeon at a public hospital, and they do surgeries Tuesdays and Thursdays because it is when they have water. When emergencies come, they just have to improvise, sometimes even paying for bottled water out of their own pockets to help people.

Also, the elevator hasn’t worked at his hospital for a long time. So, to call it, he opens the doors and screams into the shaft which floor he wants. In order to get a “quick service,” he befriended the person who operates the elevator by giving him food. All of this while trying to save lives on a daily basis.

If you need surgery in Venezuela, you are given a list of things you have to bring to the hospital, including medicine and sometimes surgical instruments and other medical staples. And then, if you do manage to find everything, you have to pray there will be water and electricity. The process of finding all the supplies is described by Venezuelans as if they are on an episode of the popular zombie show, The Walking Dead.

Many Venezuelans abroad, who can spare some money to help out — once they have helped their own families — will send money to foundations to address emergencies. I collaborate with one foundation, and one day I got an urgent message from them asking if I could help pay for exams and medicines for a newborn who was in really bad shape. I immediately said yes. To my surprise, his life was worth $23.

It is hard to come to terms with how someone can die for the cost of a lunch. But it is happening every day in Venezuela to the point that, according to the Secretary of the Organization of American States, newborns in Syria have a better chance to live than those born in Venezuela. And we are not even technically at war.

The reasons for the widespread lack of food and medicines have their roots in the Chávez era. Chávez used high oil prices as a way to subsidized food, housing and medicines. In other words, oil funded his “revolution” to create the so-called “21st century Socialism.”

With massive amounts of oil money coming in, the government imported food and medicines and then sold it at greatly subsidized prices. At the same time, Chávez overrode the free-market system by increasing regulations on prices, production and agriculture. The government seized private lands and businesses and that deeply impacted the private production of goods. When oil prices came crashing down, so did the Venezuelan economy, and the current crisis was born.

As a result, more than 3 million Venezuelans have left the country and are now living in precarious conditions all over South America, North America and Europe. Mass emigration has Venezuelans with professional careers working hard labor jobs for as little as $6 per day.

Unfortunately, this migration has also spread xenophobia against Venezuelans.

In January, Venezuelans were persecuted and harassed in Ecuador, after an isolated violent crime committed by a Venezuelan migrant. This particularly hurt, because for many years we were the richest country of the region, and we always opened our borders to immigrants. It is difficult to find a Venezuelan who does not have at least one immigrant grandparent.

The stories of what Venezuelans are enduring as immigrants in other countries are heartbreaking. From women being sexually exploited to dozens of people living herded in insalubrious spaces. But leaving everything behind is the only option to feed their families. Leaving has become the only way for young people to have a future.

There are many harrowing stories of young Venezuelan migrants. Some have bicycled in terrible conditions for months to get to Peru, Chile or Ecuador so they can try to get a job. Buying a bus or plane ticket would have been impossible. Imagine how desperate one can be to bike for months into the unknown with no money to go earn the equivalent of $10 a day.

And I’m afraid it’s only going to get worse. The United Nations estimates that there will be 5.3 million Venezuelan refugees and migrants by the end of 2019, and it’s noteworthy that this is the first time that the U.N. has set up a refugee response in Latin America, according to Human Rights Watch. This incredible figure represents 18 percent of the country’s entire population. Every single one of them deserves a home to go back to. But without some kind of change, such a return is impossible.

Maduro’s policies since he took power in 2013 have done nothing to ease the crisis, which has been getting worse year by year. A cloud of inefficiency and corruption has tainted his regime alongside a turbulent political situation.

Though it’s hard for most people to imagine today, it wasn’t that long ago when Venezuelans didn’t leave Venezuela. Some of us would go and study abroad, but nearly all of us came back because we had the belief that our country was the best — we still do. We are living in exile not because we want to, but because we are forced to. Venezuelans will go back when there are opportunities and progress. What do you do when you want to go back home, but the home you once knew no longer exists? I hope you never have to find that answer for yourself.