It’s 8 a.m. at Central City’s newly reopened Bates Hunter Mine, the sun just peaking over the valley walls. It’s been over 70 years since gold was last mined here, but as the miners begin to arrive at work on a November day in 2018, it feels like they’ve been here all along, like this is where they’re supposed to be. By all appearances today is a normal day, although on the agenda is at least one extraordinary task; after months of removing water from the main shaft, the miners can finally access the 163-foot level, submerged and unseen since an exploratory visit in 2008. And, aside from a few maps that look like a simplistic version of Snakes and Ladders, the crew doesn’t really know what to expect on today’s seminal descent.

“We’re just gonna go down and check it out, gauge the condition of the infrastructure, poke around on the landing,” says Matt Collins, the mine’s general manager and engineer. “It’ll be neat to see how close these are to our maps.”

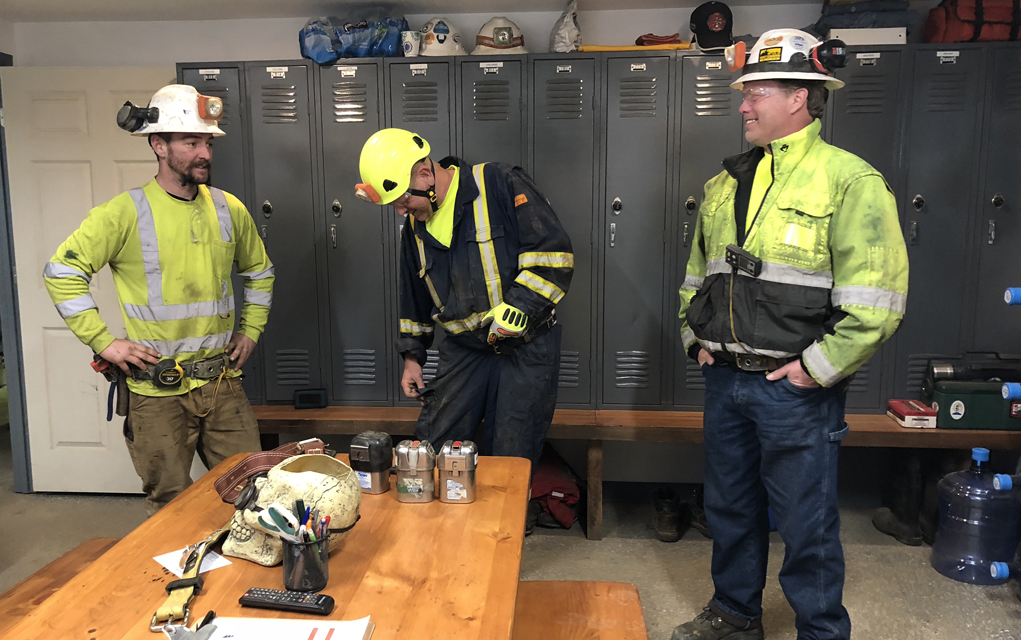

In hopes of extracting ore by the end of the year, the miners have already been hard at work getting the site in working order: cleaning the shop, retrofitting the water treatment plant and dewatering the mine. For the most part, those tasks will continue to be the bulk of their daily work, but, even with today’s pioneering task added to the list, there’s still another hour of routine to attend to.

The miners still need at least one more cup of coffee, they still need to gear up and attend the daily safety meeting. Then, last on the list before the descent is the final and solemn rite of passage: to check in at the brass board.

There’s a brass board at just about every mine in the world and every morning, every miner must face it before entering the mine. They must take their identifying tags and move one to the line reading “in,” while fastening the other securely to their body. It’s an old-fashioned system addressing the worst-case scenarios of the job: at the end of the day a way to know if a miner is still below or, in case of emergency, to identify a body killed in the course of performing one of the world’s most dangerous jobs. Although these days, and in this country, accidents are rare and fatalities rarer still (in the last five years there have been two fatalities in Colorado mines). Nonetheless, there is an ever-present gravity in a daily miner’s task, one that they’re accustomed to confronting at the start and end of each day.

“I always think of my wife,” one miner says as he grabs his brass. “But I don’t tell her that because I don’t want her to worry.”

With the ID tags attended to, the hard rock gold miners at Bates Hunter are now ready to enter the shaft, ready to travel down hundreds of feet of granite into the dark, one rickety ladder step at a time. Built from aged two-by-fours, the ladders are damp with the moisture in the slowly dewatering mine and are slippery to the touch. They warn against relying on the rungs (“you can trust the wood but not the iron nails”), but there’s no real way to avoid them entirely; best to step on them gingerly, maintain three points of contact and hold on to the side rails as you go down the aged shafts built over 100 years ago.

The Bates Hunter Mine (actually a conglomeration of the Bates Mine and the Hunter Mine) is rumored to be the second mine claimed in Central City in 1859, Sarah Haas but, according to Dr. David Forsyth, executive director of the Gilpin Historical Society, it hasn’t been historically significant until lately, now that it’s reopened for business, making it the first operational mine in city limits in more than 80 years.

For a historian interested in mining history, there might be no better place to be stationed than Central City, the origin site of the Colorado Gold Rush and the notoriously touted “richest square mile on earth.” The town’s origin story is among its most famous, and Forsyth knows it by heart.

It begins with a man named John Gregory, a placer miner panning for gold at the foot of Clear Creek. Unsatisfied with the flakes he collected, he turned his attention uphill, following the water upstream until the gold flakes disappeared from the water, an indication he had passed the mineral’s source. Whether by luck or cunning, this was how he discovered his namesake Gregory Vein, and as soon as weather permitted, he staked the very first few claims.

Within weeks, more than 30,000 miners had staked thousands of claims and a haphazard town came to life to support the burgeoning industry. Precarious wooden houses were built on cliffs and ramshackle stores took shape. But mining in those early days wasn’t just difficult and dangerous, it was also expensive. Lacking the necessary funds, the boom town dwindled quickly. By the 1870 census, only a few hundred miners remained.

Those who stayed were not interested in getting rich quick but, knowing they needed to attract investors, looked to build the necessary infrastructure for a long-lasting industry. And so they were quick to turn the shanty town into a bona fide society, demolishing the mining shacks and replacing them with the brick-and-mortar buildings that still stand today. To govern the town, they established a regimen of law and order and brought their wives and children to help elevate their culture. And, by 1878, they’d even brought the train to town, having laid tracks all the way from Denver to Central City. But it was too late.

By then, new gold lodes had been discovered in the state, in Aspen and Cripple Creek, and money followed the prospector’s promise. Meanwhile, mines in the Central City area were closing faster than they opened and by 1910 only a few remained. Some were operational but most were used as scams for dubious businessmen to draw funds from wealthy European investors, rarely returning investments and usually escaping obligations through declarations of bankruptcy.

Somehow, though, both the Bates and Hunter Mines kept producing through the difficult times, even enduring World War I. By 1936 it’d established shafts down to 700 feet but, in that same year, President Roosevelt declared ownership of monetary gold illegal with the Gold Reserve Act, sending gold prices plummeting. Many of the mines, including Bates Hunter, were abandoned and have been more or less untouched since then.

“When the mines stopped operating, they left an awful lot of gold in the Earth,” Forsyth says. “When all is said and done, only 10 to 15 percent of the gold was extracted, which means there’s still at least 85 percent of it down there.”

Both Forsyth and current mine manager Collins speculate that in other countries with less regulation, the now gambling towns of Central City and Black Hawk would have long ago been demolished to get at the loot. With the spot price of gold hovering around $1,200 per ounce, the area’s lode is valued in the tens of billions of dollars, (the Bates Hunter Mine alone speculatively contains upwards of $2 billion), a prize many governments and business owners would pursue without hesitation.

But here in the United States, mining regulations have evolved to protect both the environment and workers, making mining a cleaner and safer but ultimately more expensive endeavor. Since the 1970s, federal mining regulations have tightened according to such legislation as the 1972 Clean Water Act, requiring mines like Bates Hunter to build expensive water treatment plants that return high-quality water to watersheds. And, the 1977 Mine Safety and Health Act established safety measures like the necessary presence of a secondary escape route, an unfeasible retrofit for many smaller mining operations to accommodate.

Despite the costs to the industry, the steps were enacted in response to glaring evidence of the environmental and safety risks posed by mining. Since the end of the gold era in the 1930s, Central City, like many of the other mining towns in Colorado, have been engaged in monumental clean-up acts. One of the largest designated Superfund sites, the Central City, Clear Creek area — a 400-square-mile watershed extending from the Continental Divide east to near Golden — was placed on the original National Priorities List in 1983.

Steve Laudeman with the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment identifies upwards of 30 specific sites in need of attention within the Superfund site, two of which are located in Central City.

“As a whole, we initially looked at the site as a study area, evaluating it so that we might narrow it down to specific sites in need of remediation,” Laudeman says. “At this point, the few sites located in Central City (namely piles of toxic mining debris) are in maintenance mode: with major remediations accomplished we now monitor them on a regular basis.

“Our bigger focus now is on restoring the water quality of Clear Creek. As of last year we completed construction of a water treatment facility downstream from Black Hawk that is treating water in hopes of restoring surrounding ecosystems.”

When asked if there was a date in which remediation efforts would be completed Laudeman simply says, “No, and I don’t think there ever will be.”

But neither Laudeman nor the Colorado Department of Natural Resources’ Division of Mining and Reclamation believe new mining activity poses a threat. If the Bates Hunter Mine operates according to the rules and regulations, they say environmental threats should be stymied.

Bates Hunter Mine manager Matt Collins agrees and pushes a little further, saying heightened standards ought to be viewed as a reason to mine domestically, where we know it’s being done right.

“We all use gold, as an investment, in our jewelry, in our cell phones. That will not change. So why not mine it here, mine it responsibly, safely and with as little impact on the environment as possible?”

Speaking from his desk in the otherwise orderly Bates Hunter Mine, Collins’ area is stacked high with thick books about chemistry, piles of papers, maps and random pieces of small equipment that need attention. Positioned in between the mining operations and the investors that hover above, Collins is a modern day renaissance man, whose job is to know and execute everything from payroll to building a lab in which to test the gold that’ll be mined in the near future.

“The regulations are expensive, and were it not for the equipment and infrastructure that this mine already has (estimated at $40 million), the barrier to entry would simply be too high,” he says. “This mine is a dream come true, it’s got an active permit, a lot of potential, a great infrastructure, a neat history and, with the mill site located just a mile down the road in Black Hawk (most industrial gold mills in the United States are shuttered, making processing a costly international endeavor), we might just be able to pull this off.”

Above his desk is a long list of tasks that need to be completed in order to make the dream possible. Number one, fix up the mill. Number two, create a report for investors… Number 10, “Dream Big.”

“That one comes from the man who made all this possible,” he says, turning to point at a makeshift shrine hanging above a copy machine. “It was the mantra of the guy who bought this place in the 1980s, George Otten [now deceased]. Without him and his foresight, this mine would have been shuttered like the rest of them.”

A coin-operated car wash entrepreneur turned miner, Otten comes from an older generation of miners who might best be described as curmudgeons: “His generation was the ones who invented the best practices that got turned into regulations, and they weren’t very fond of the regulations,” Collins says with a laugh.

Which is to say that where others saw obstacles, Otten saw opportunity, scooping up both the mine and the mill site and acquiring active permits for both in 1990. In 2004, Otten started to dewater the mine but before he could produce any gold, he met the fate of so many miners of yesteryear: he ran out of money.

Shuttering operations in 2008, Otten began to look for financial backers, which he quickly found in the GS Mine Company (a spin-off of BH Mine Company), which not only thought the site promising in terms of extraction, but believed it presented the perfect case study to try a new method of fundraising by way of cryptocurrency.

Soon, the company’s “Moria Tokens” will be available to any investor with Bitcoin or Ethereum and will represent ownership of royalties from the Bates Hunter Mine. Advertised as the “first cryptocurrency to provide immediate cash flow,” GS Mine Company aims to attract a lot of newer and smaller investors who wouldn’t otherwise have the capital to invest in gold mining.

Among the first mines in the world to offer its own cryptocurrency, the effectiveness and payouts of the Bates Hunter Mine are yet to be seen. If successful, the currency could help small mining operations overcome the high barriers to entry facing the domestic industry. But scrupulous onlookers, like Dr. Forsyth at the Gilpin History Mining Museum, says the schema seems eerily familiar to the mining scams of the past.

From the insider’s vantage point, Collins says he’s withholding judgment, “Heck, I’m optimistic. From where I stand we are building up a robust mining operation here. We have lofty goals and we’re meeting all of them on schedule. But, of course, the real test is if we can get some gold up out of the mine, which we should know by the end of next quarter. So far, all signs are pointing to yes.”

And so, at least for the foreseeable future, the 11 miners at the Bates Hunter Mine will continue to wake up before dawn to get to work by daybreak. They will sip on their coffee, put on their gear, and sit through their safety meetings. Inevitably, they will come face to face with the brass board and take a moment to reflect on life and what they are living for.

“I just love it down here,” a miner nicknamed Foo says. “This has got to be the greatest job in the world. You work with your hands, you explore the depths of the Earth, you get to tackle incredibly difficult tasks that most people would call impossible. And, we get to mine gold in a place that’s longing for a return to that history.

“Just don’t tell my wife too much about it. She’ll worry.”

Correction: The original version of the story misstated the estimated lode of Bates Hunter Mine is worth $2 million. We apologize for any inconvenience.