Finding out that contemporary Nashville musicians are including cannabis in their songwriting got me to thinking about how cannabis made its way into popular songs and culture.

THC, the active ingredient in cannabis that stimulates the frontal lobe of the brain, which has to do with creativity, among other things, has been a favorite drug among musicians at least dating back to the days when recording began and, I suspect, a lot earlier than that.

My first exposure to a drug reference in a song came in 1963 via a relatively innocuous song about growing up. “Puff the Magic Dragon” was written by Peter Yarrow and Leonard Lipton and performed by Peter, Paul & Mary on the 1963 album Moving. I was 16, already a huge PP&M fan, and I identified with the story of Jackie Paper moving away from childhood — “Painted wings and giant rings make way for other toys” — and I would have been blissfully unaware of its so-called cannabis references had I not read about them in national publications.

The song created quite a stir at the time, but today the evidence for veiled reefer references is slim to non-existent. Claims included the use of the word Paper for the name of the boy (a reference to rolling papers?), while other conspiracy theorists suggested that dragon could be construed as “drag on,” as if on a joint, you know. Yarrow, who added the melody to a Lipton poem, has continuously, flatly denied that it was anything more than a song about a boy giving up childish things, but people will believe what they will.

The first time I saw musicians smoking cannabis was in 1964. We got free tickets to see Louis Armstrong, then in his early 60s and riding the popularity of “Hello Dolly,” at the Municipal Auditorium in Kansas City. The free seats were high behind the stage of a 10,000-seat arena, and Armstrong, who had a large band with him, broke into “Dolly” at least three times that afternoon.

But the most interesting part was during the instrumental portions, when Armstrong and some of the band would retire backstage, and we were far enough above them that we could see them passing something they were smoking. It wasn’t until a few years later, reading about Armstrong’s documented affinity for cannabis, that I figured out what they were doing.

And then along came Bob Dylan. “Mr. Tambourine Man,” which became a huge hit for The Byrds in 1965, was considered a drug song from the outset, mostly because of its “trippy” lyrics that described magic swirling ships and senses stripped. And Dylan’s “Rainy Day Women #12 and 35,” released in 1966 on the Blonde on Blonde album, has also been categorized as a drug song. Its refrain is pretty obvious — “everybody must get stoned” — and it went to No. 2 on the charts as a single.

I wouldn’t presume to second-guess Dylan’s songwriting intentions, but “Rainy Day Women” is open to interpretation. Each verse begins with “they’ll stone ya when,” which I hear as Dylan laughing and leering at those who were already criticizing him for various offenses against music, i.e., not continuing to write “protest” or topical songs or for “going electric” (“They’ll stone ya when you’re tryin’ to make a buck/They’ll stone ya and then they’ll say, ‘good luck.’”) That said, the general frivolity of the production, which emphasizes raucous laughter among the musicians — Howard Sounes’ biography, Down the Line, says that Dylan passed out joints at the recording session — the wheezing, almost out-of-control horn charts and the cheerleading quality of the refrain strongly suggest the drug connection. I could go either way.

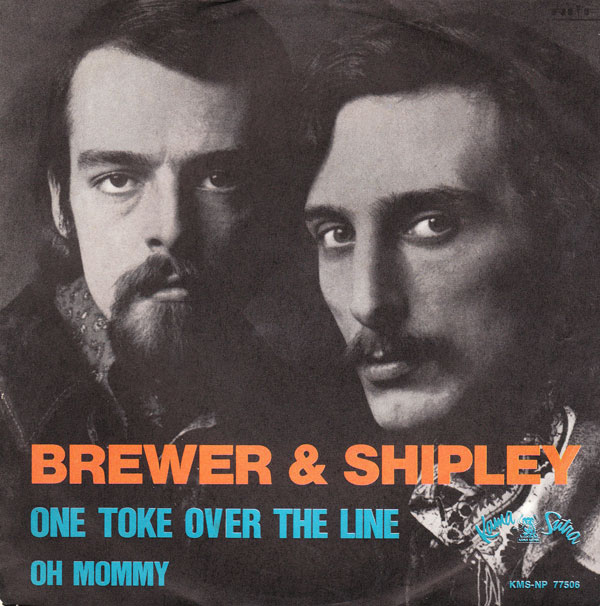

But my all-time best dope-song story concerns the misappropriation of an actual cannabis song by a most unlikely source. I was on the couch, must have been 1970 or 1971, and on came The Lawrence Welk Show. Myron Floren, Welk’s prominent accordionist, introduced Gail and Dale to sing one of the “newer songs.” Whereupon, in perfect harmony and with Pepsodent smiles, the duo performed Brewer & Shipley’s “One Toke Over the Line.”

Welk came on afterwards and praised the song as “a modern spiritual.” I almost fell off the couch laughing. Brewer & Shipley were based in Kansas City when they had their day, and I was pretty proud that two local hippies had gotten into the Top 40 with such an obvious cannabis reference. Another song on the Tarkio album, “Tarkio Road,” was about two long-hairs moving product on their motorcycles along the back roads of Missouri and Nebraska. All I could imagine was that Welk’s people, in a sincere attempt to attract a younger audience in the era of Jesus Christ Superstar and Godspell, might have missed the meaning of “toke,” but they sure as hell knew what “sweet Jesus” meant.

I repeated the story to friends, and after awhile, I began to question if it were actually true or if I had just been stoned and imagined it. But in the early 1980s, Michael Brewer, who co-wrote the song with Shipley, confirmed the Welk story for me during an interview with the Kansas City Times.

I didn’t see the clip again until the YouTube era.

Now anyone can see a truly great countercultural moment by typing “Lawrence Welk One Toke Over the Line” into YouTube’s search engine.

Send tips, suggestions and criticisms to [email protected].

Respond: [email protected]