When she’s not writing fiction, Kristie Betts Letter teaches her 10th grade students how to fail.

Not how to do it intentionally, of course, but how to do it with intention, with an eye toward the moments after failure — what do you know now that you didn’t know before?

Failure is just possibility in disguise.

Not long ago, the Peak to Peak Charter School English teacher convinced her boss to let her develop and teach a class on design thinking, a problem-solving methodology that focuses on human needs. Tasked with plainly weird problems, like how to develop an environmentally friendly use for dehydrated orange pulp, her students don’t just think outside the box, they pretend there’s no box at all.

“They have to get comfortable with failure,” Letter tells me one evening after school. “They’ve got to get comfortable with, ‘So I tried this thing and it’s terrible. So I have to do it again, I have to keep trying, and even if it never works, it was an interesting experiment.’

“So we keep doing things,” Letter says, partially referring to her students, partially to humans in general, “which is such a metaphor for being creative in any particular way — but you have to fail all the time. I mean, that’s what we do.”

Humans fail. Simple as that.

But we all know it’s not as simple as that, that failure hurts so much we often bury it to keep others from seeing the ugliness of our blunders.

What would we be, though, without missteps? And what does failure look like from different angles — does it sometimes look like success? Like freedom? Like self-confidence?

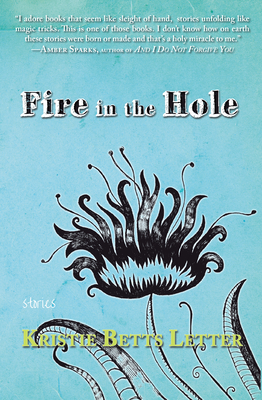

Letter explores the quirks and foibles we often call failure in her first collection of short stories, Fire in the Hole, a labor of love forged over the better part of a decade.

The collection opens with “Silver Cornet Band,” set in the newly chartered town of Caribou, Colorado, in the early 1970s. The town, with veins of silver, gold and lead snaking beneath the earth, was prone to lightning strikes, with winds that would sweep you “clean off the mountain.”

Letter uses second person to pull the reader into the story. You are the new bride of an asthmatic Christian cobbler whose only interesting characteristic is his talent on the cornet.

When the wind chaps your husband’s lips so badly he can’t practice his instrument, you, the bored but dutiful wife, turn to the only people in town who understand skin care: prostitutes.

Here, Letter wonders about the “failures” of women; those who become whores, those who marry the first man who offers them a silver ring. Which of these women is good, and which is bad?

“People get so invested in separating themselves,” Letter says, “but if you actually need some really good salve, I don’t know that those distinctions are going to matter much. If you need help, if you need wisdom, the little walls that we build don’t really work so well.”

Letter was born in the admittedly fictional sounding town of Stony Bottom, West Virginia, where her family lived at times with no electricity. The ancient rolling hills of Appalachia make their way into her work as much as the juvenile jagged jebels of Colorado. Her stories often explore the subterranean: old mining towns burning from underneath, a grave plot that’s been unexpectedly occupied by someone other than the person who purchased it, an old cellar that leads a traveler to a hyper-focused beekeeper.

Other times, what’s underneath is not always so literal.

“The surface of a person is one thing, but then there’s always something else beneath it,” Letter says.

Those are the places where we hide our failures, the things we think the world will reject.

While Letter was a graduate student at CU Boulder, she took a class with the chronically underappreciated short story writer Lucia Berlin. Like Berlin, Letter mines her own background to write stories that might very well be autobiographical, but the details are exaggerated or rearranged, names are changed, places are shifted.

In the title story, a woman is tasked by her mother to go and fetch her spinster aunts from a town that is slowly succumbing to a smoldering mine fire. The woman’s father, a devout Catholic, is buried in the town cemetery, despite his wishes to be cremated.

Letter has relatives buried in the abandoned town of Centralia, Pennsylvania, where a coal mine fire has been burning since 1962.

“We have relatives who are, not by choice, basically being cremated because they’re buried in Centralia,” Letter says.

The story suggests that no matter how deeply we bury something — whether that’s wanton desire, alcoholism or a body — the universe has a way of unearthing what’s beneath the surface.

In her collection, Letter asks us whether our failures are really as bad as we think they are, and what we might learn from them. Were they really failures, or can we skip the negative label and just get straight to the growth?

Reading Fire in the Hole makes you wish Letter had been your teacher in high school.

ON THE BILL: Kristie Betts Letter — ‘Fire in the Hole.’ 6:30 p.m. Boulder Book Store, 1107 Pearl St., Boulder.