Adriana Corral’s art explores the human condition and our fundamental rights. Her research-based process has taken her from her home in Texas to present-day refugee camps and former concentration camps in Germany and Poland. When she returned to the U.S. and discussed her findings with her father, he told her about a troubling piece of history right in their home state that she’d never known.

In 1942, the U.S. federal government worked with Mexico to establish the Bracero Program — “bracero” translating, literally, to “one who works with his arms” — to bring skilled Mexican workers to the States to fill labor shortages during World War II. The program processed more than 5 million workers, making it one of the largest foreign-worker programs in American history, and it continued to operate well after the war was over. The Rio Vista Farm processed roughly 80,000 workers each year from 1951 to 1964. The program guaranteed decent living conditions and a minimum wage of 30 cents an hour, but the mostly male workers were not met with friendly conditions. The National Trust for Historic Preservation refers to the program as a time of “legalized slavery.”

“Men were stripped and then fumigated, as were their clothes and luggage, with the toxic chemical DDT upon entry in the United States, where they toiled under difficult and unsanitary conditions on farms and railroads,” Corral says in an email.

In 2018, in partnership with Denver-based nomadic art museum Black Cube, Corral installed a 60-foot flagpole at the still-standing Rio Vista Farm to acknowledge and memorialize all that took place there. The cotton flag she created features a bald eagle and a golden eagle, emblems for America and Mexico respectively, talon to talon, almost as if in battle. The flag was placed in the same spot where the processing center had previously flown a U.S. and Mexican flag side by side, representing unification, Corral says.

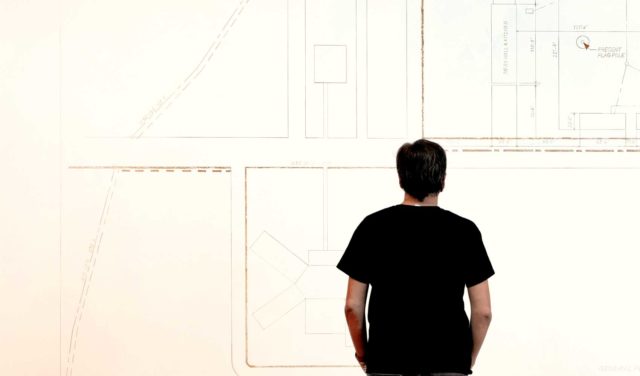

Now on display at the Boulder Museum of Contemporary Art (BMoCA), Unearthed: Desenterrado features Corral’s flag and other corresponding pieces about Rio Vista Farms and human rights. The exhibit presents a blueprint of the processing center and imprints from the soil, framed by Corral’s chilling interpretation of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

“The architecture at Rio Vista has a haunting, historical presence, and I felt compelled to address its unacknowledged history,” Corral says. “Unearthed: Desenterrado emphasizes the importance of recognizing and confronting the voids within our American history.”

The Bracero Program is just one example in an endless list of inequalities that have plagued the U.S. and the world. Laborers worked under grueling conditions and were given a wage that was one-third of the country’s standard. Cortney Lane Stell, curator for the show and executive director of Black Cube, acknowledges the stigma and misinformation that led to workers being sprayed with hazardous chemicals in order to stop the spreading of disease.

“It’s an important part of American history that really speaks to this legacy and understanding of people from the south needing to be purified or cleansed or sterilized in some way,” Stell says.

Yet the contributions of the braceros were vital to building the backbone of America. They worked on farms and railroads throughout the U.S. It’s this contribution that Corral strives to highlight. She chose cotton for the material of the flag to represent the cotton fields around the Rio Vista Center.

“By using this material, it directly referred to [Rio Vista] and other [bracero processing sites] across America, and is an acknowledgment to immigrant laborers who support the infrastructure of this country,” she says. “The many individuals who work to provide clothing and fabrics in the textile industry, food on the dinner tables, construct our cities, serve in our militaries, work in our factories and serve as nannies raising American children. Mexican [laborers] have been, and continue to be, a part of the very fabric of this country, along with others unrecognized.”

Even the construction of the flag leads back to these marginalized laborers.

“I worked with an amazing seamstress to create the flag, Lucy Rodriguez,” Corral says. “She has worked on many large projects, but what I found most compelling was learning that she had sewed the (2016) inaugural flags for the White House. It makes me wonder, do the American people know that a fierce Latina woman is responsible for sewing our American flags? And not only her, but a whole team of Latina women?”

Materials and who made them are important factors in Corral’s work. As a minimalist artist, the materials themselves are just as essential and meaningful as the finished product. While most flags today are made of durable vinyl, Corral’s cotton flag is much more vulnerable to the elements. In BMoCA, the flag sits on a pillar, discolored, tattered and worn. The choice was intentional, Stell says, to symbolize the deterioration of the human body.

Soil is another element in Unearthed. Sculptures capture imprints of the soil collected at Rio Vista Farm. Corral’s large-scale drawing of the center’s blueprint is also drawn using pastels made from the soil.

“These workers were working with the earth mainly, whether it was building railroads or cultivating farms. They were working directly with their body and the elements and improving our earth, the United States’ land,” Stell says. “Also, I think earth is a metaphor in her art for where the body returns when it’s dead. … The material shows the fragility of the human body. We are from the earth, taking care of the earth.”

Corral’s minimalist approach gives her work a quiet stoicism. A lack of stimuli creates mental space where the audience can meditate on the greater implications of her themes. She says that while her work is visually minimal, it is maximal in content, capturing the density of the subject matter with a slower, subtler approach.

Showcasing the absence of voices is a major theme in Corral’s work, Stell says. The artist plays with the balance between presence and absence in how she presents her art.

“It’s important to acknowledge she’s dealing with this in a poetic way,” Stell says. “Even though she’s dealing with history that she could speak about with facts that would be overwhelming and interesting for us to look at, I think what she’s doing is providing a sensory experience and allowing us to struggle with reading the work, to try to understand it, to make inferences of our own.”

One of the most striking pieces in Unearthed is “Latitudes.” The artwork is made up of a series of frames containing white pieces of paper. From far away, the pages look blank, but upon closer inspection you can read the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) debossed on the paper in both English and Spanish. The white on white speaks volumes about the impact of the document — it’s there but it takes effort and persistence to read, let alone to implement.

Corral uses the UDHR as a core text in her research. The document was created by the United Nations in 1948, in the shadow of the Holocaust and World War II, guaranteeing fundamental freedoms. Through “Latitudes,” Corral demonstrates the failure of diplomatic language and the consequences of violence that still plagues the world.

“In the UDHR I find myself questioning the rule of law — how it mitigates justice and often fails us,” Corral says. “If the letter of the law was created to protect us, why do we find ourselves in a cycle, again and again fighting for the basic right to life? What mentality perpetuates such cyclical complexity? When we are left with the body’s traces, how does one decipher its tangible or ephemeral quality?”

It’s impossible to see Unearthed and not consider present-day discrimination in the U.S. and abroad.

The Bracero Program is a long-forgotten example of mistreatment. A half-century later, we bear witness to new forms of the same old bigotry as immigrant children are separated from their parents at the border and asylum seekers die in overcrowded detention facilities.

And yet, Stell sees hope in Corral’s work. While her art forces us to reckon with the reality of discrimination, it also alludes to a more humane future.

“By acknowledging these violations or atrocities — it’s not about blame,” Stell says. “It’s about acknowledging it all, a sense that we can all be better. She sees the function in memorialization as positive in our community and for the health of our society.”

When we unceremoniously bury history — no eulogy, no acknowledgement — we’re doomed to be haunted by its specter. Corral unearths what we’ve tried to forget and forces us to ask ourselves us why we buried it in the first place… and why so little has changed.

ON THE BILL: ‘Unearthed: Desenterrado’ by Adriana Corral. Boulder Museum of Contemporary Art, 1750 13th St., Boulder. Through Jan. 19.