It’s 10 a.m. on a recent Thursday and Jordan Casteel has been up since 5, but she’s fresh, bright-eyed, no signs of fatigue. The Denver-born, now Harlem-based artist could barely sleep the night before, excited about this particular homecoming. In oversize black-framed glasses and effortlessly cool khaki coveralls, Casteel is every inch an artist physically, but metaphysically she may as well be the Sun, radiating light, drawing people closer to her warmth as she stands in front of the glass doors of the Gallagher Gallery at the Denver Art Museum (DAM).

She is home, literally and figuratively.

This is Casteel’s first major museum exhibition, Returning the Gaze, a collection of 29 large-scale portraits of the black people who populate her world: friends, family, lovers, strangers she meets on the streets of Harlem (though no one’s a stranger for long with Casteel).

Of course she’s excited about seeing the exhibition itself — Casteel spent summer evenings as a child making art at overnight events at DAM in the early ’90s, adding a layer of nostalgia and meaning to this show — but it’s the people, the subjects of her paintings, that fuel her emotional fire today.

“These stories are of me,” she says of her paintings before leading a tour of the exhibit. “All of these people are alive and well, and some of them are arriving soon to see these paintings in person for the first time.

“I look forward to you getting to know these people.”

Here is the essence of Casteel’s vision as an artist: To capture the human desire to be known, to be understood, to be seen. Returning the Gaze turns the viewer into the viewed — Casteel’s subjects staring sweetly at you as you size them up — exploring what it means to see and been seen, particularly as a person of color in America.

Like famed African American artists Charles Alston, Jacob Lawrence and Gwendolyn Knight before her, Casteel uses portraiture to call attention to black identities. Her earliest works in Returning the Gaze focus on black men, stripping them of their clothes but hiding their genitals. The works allude to the hypersexualization of the black male body, so often portrayed in mainstream culture as simultaneously erotic and terrifying. Casteel presents them as vulnerable, posed in the comfort of their own homes on thrift store-chic floral couches (a phenomenon Casteel attributes to the fact that the men in these early works were theater students at Yale, where Casteel received her master’s in fine art in 2014). There are no black tropes in Casteel’s work, no scary black men or soul brothers, only young men politely returning your gaze.

“I felt that the world didn’t see and know them as I see and know them: as my brothers, as my father, as friends, as lovers,” Casteel wrote in an artist’s statement. “I felt I had access to a kind of intimacy that I could give other people access to through painting.”

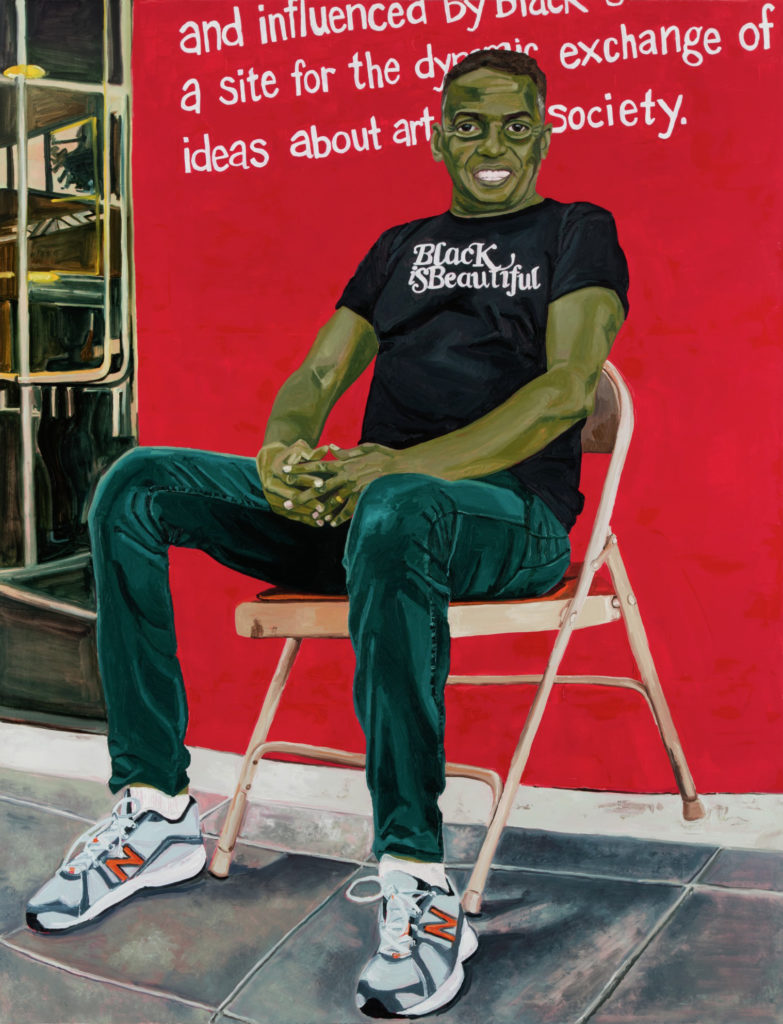

But Casteel’s message with these paintings is layered; her 2014 piece “Galen 2” depicts a strapping young man sitting on a folding chair in a kitchen, the familiar checkered pattern of the floor reflected in the appliances surrounding him. He’s obviously black, and yet he’s not; he’s quite obviously green.

“I was thinking about how we approach people with assumptions,” Casteel says. “Black families are so diverse, so what does it mean to be a person of color?”

Casteel’s work forces the viewer to slow down, to look again and re-evaluate. Text often finds its way into her paintings organically, appearing on walls and signs and T-shirts. In her 2017 piece “The Baayfalls,” a woman and man in Harlem sit by their street-side stand of African jewelry. The woman’s shirt reads, “I am not interested in competing with anyone. I hope we all make it.” The subject of Casteel’s work “Timothy” wears a shirt that simply reads, “Black is beautiful.”

For Casteel, these powerful statements on clothing not only give the viewer an inside look at the subject’s personality, they act like shields for the subject, invisibly fighting off negative attitudes and stereotypes about black Americans.

Like Alston, Lawrence, Knight and many other iconic black artists, Casteel has found a home for herself in Harlem; she liked “the entrepreneurship” she found there, “how people found space on the street to call their own.”

In Harlem, Casteel has found space of her own, a respite from the hectic existence she’d lived in other parts of New York City, and a neighborhood bursting with culture and resilience.

But there are pieces of her Denver roots spread throughout the exhibit. In “Marcus and Jace,” Casteel offers a glimpse inside her personal life. Marcus Pope, a barber at House of Hair in Denver, has been a friend of the Casteel family for more than a decade. He cut Casteel’s hair just a few days ago, and today, during the preview of the exhibition, he’ll see the piece Casteel painted of him and his son Jace for the first time.

“Putting aside Jordan’s skills as an oil painter,” Pope wrote in a statement, “I think her gift is to capture these moments and send a message to the world that even the common Joe at the barbershop, the common barber, the common individual in the community, [at] the bus stop, is worthy of being celebrated.”

But Returning the Gaze is about more than just representing black identities; it’s about including them in spaces where they are often absent.

Like art galleries.

“I hope to change the culture of viewing art,” Casteel says, her voice catching in her throat. “Encouraging people of color to feel welcome in art, seeing yourself represented in an art museum…” She pauses to take a breath and fight back the tears. “It can open doors.”

It takes artists like Casteel to open those doors.

ON THE BILL: Jordan Casteel: Returning the Gaze. Denver Art Museum, 100 W. 14th Ave. Parkway, Denver. Through Aug. 18.