George Lange kept the box shut for nearly 40 years. So long as he did, his old friend Francesca Woodman stayed alive, in a way.

The box was a time capsule of their friendship, a snapshot of their time at the Rhode Island School of Design, where both studied photography in the late ’70s. There was an old French fry, some handwritten invitations from Woodman inviting Lange over to her loft for ice cream, letters from Woodman’s father, postcards from her mother and, of course, photographs.

When Woodman left RISD for New York, she told Lange to grab whatever he wanted from her loft in Providence. That’s what filled the box.

Lange could hardly know his friend would take her own life soon after.

Plenty has been said about Francesca Woodman’s death, about her serious nature and serious work ethic; about her artist parents, George and Betty, and their nontraditional approach to raising Francesca and her brother, Charlie; about how Francesca’s fame far overshadowed her parents’ art; about how the young photographer from Boulder struggled to find an audience for her work during her final years in New York before death, as it so often does, made her brilliance impossible to ignore.

But when Lange looked at the box, all he could think about was friendship.

“You have this feeling that as long as you don’t open it that she’s still alive inside of the box — and she kind of was,” Lange says over the phone from his home in Pittsburgh. “And then her mother … and her father created this legacy for her and she became very famous.

“It was all done under the cloud — not that they wanted it to be that way — but it wound up being under the cloud of her death, kind of like Sylvia Plath, and everything was seen through that filter,” Lange says. “So no one ever saw a picture of her smiling — ever. And we laughed a lot. She was silly, you know, not all the time, but here was that whole piece of it. So this whole narrative went out in the world and she became very well-known and the work was beautiful and all that, but I felt like there was a single chapter that I had experienced with her.”

Inside the box Lange carried with him for decades was a chapter of Woodman’s life Lange thought the world ought to see. A chapter with smiles and French fries and ice cream. Through mutual acquaintances, Lange made contact with Nora Burnett Abrams, director of the Museum of Contemporary Art Denver, who used the box of memories to mount Francesca Woodman: Portrait of a Reputation at the museum. Together, they published a book of the same name.

A hallmark of Abrams’ curatorial work is her interest in the lesser-known narratives of an artist’s life. As curator at MCA in 2017, she presented Basquiat Before Basquiat: East 12th Street, 1979-1980, a collection of works made by the artist during the years he shared a small apartment in the East Village in New York with his friend Alexis Adler.

When George Lange approached her with his box of memories of Francesca Woodman, Abrams understood exactly what the box represented to him.

“What George cared very much about and I recognized was the human aspect to this material,” Abrams says. “He had letters that had nothing to do with her artwork. They are just lines between friends. … There was just so much joy and silliness and kind of character and personality that was contained in that. He wanted to make sure in sharing it with the world we preserved that. I recognized that’s what made this body of work he had so special. We’re going to allow people to see this artist as a person, not a mythic figure. [Woodman’s] work is enigmatic and it’s so suggestive of a lot of different ideas and themes. She can’t be pinned down. The nature of her death allowed people to treat the material very seriously and with so much gravitas … but there’s so much more. She was joyful in the studio.”

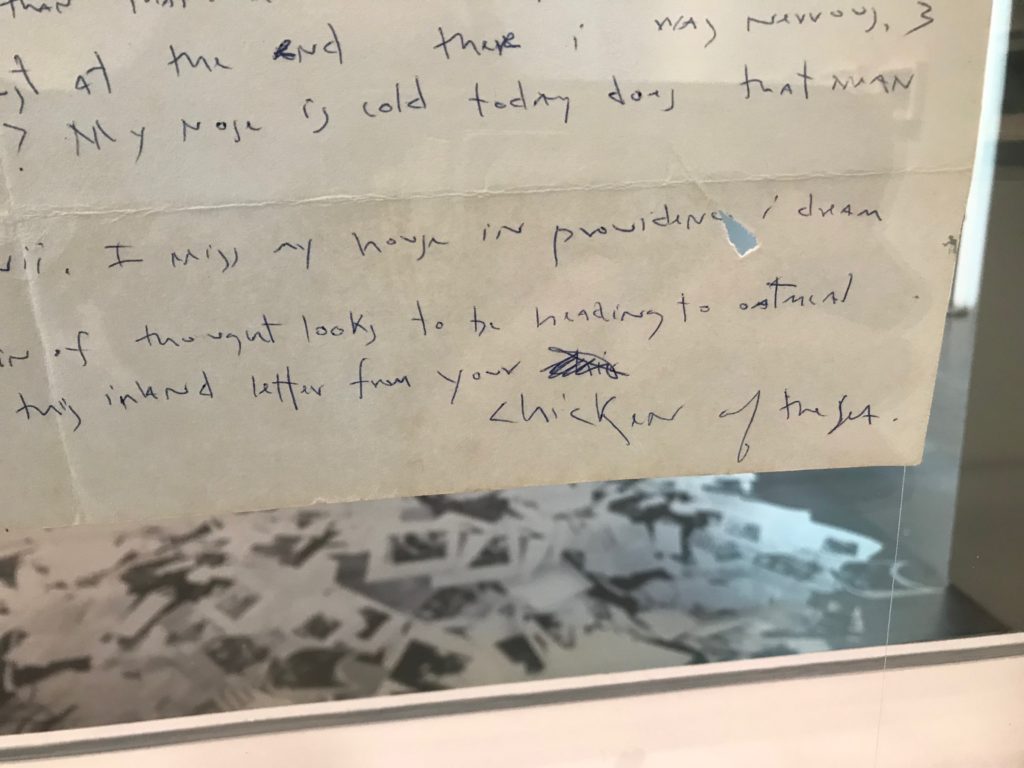

Woodman’s handwritten letters are particularly intimate, with her angular penmanship, puns, inside jokes and stream-of-consciousness approach to communication. In a letter to Lange, she mentions missing her house in Providence, wonders what it means when her nose is cold, then admits her “train of thought looks to be heading to oatmeal.” She signs off, “your chicken of the sea.”

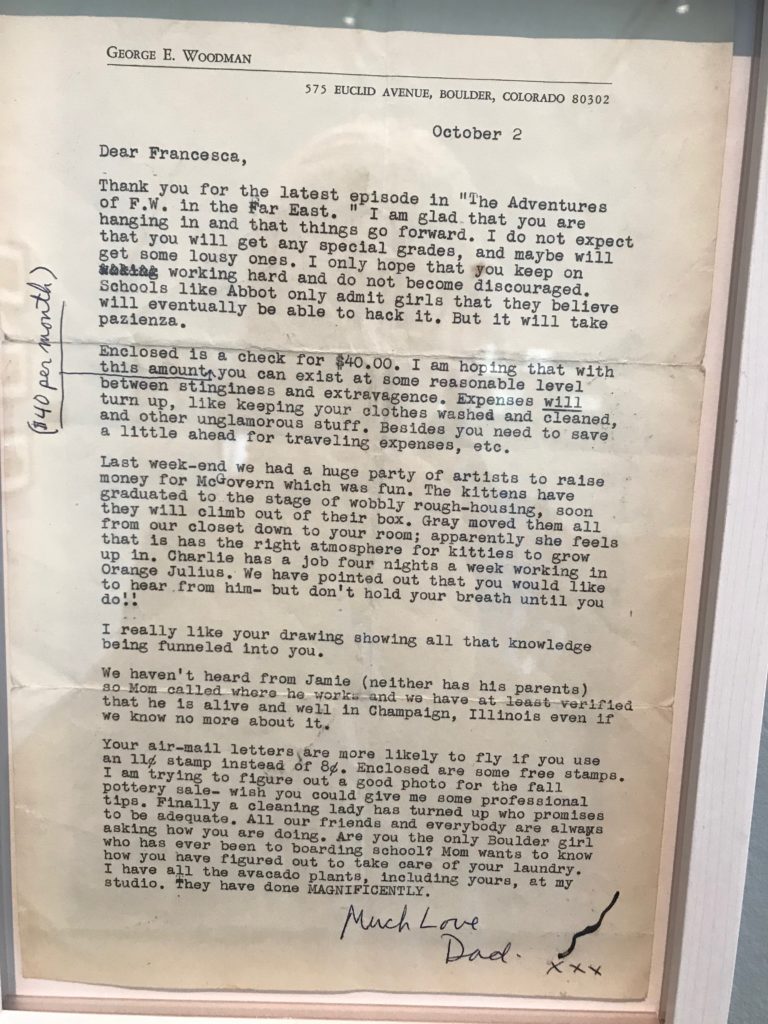

Letters from her father remind that Woodman was a teenager as well as a talented artist.

“Enclosed is a check for $40.00,” George Woodman writes his daughter while she’s away at boarding school in Massachusetts. “I am hoping that with this amount you can exist at some reasonable level between stinginess and extravagance. Expenses will turn up, like keeping your clothes washed and cleaned, and other unglamorous stuff. Besides you need to save a little ahead for traveling expenses, etc.” He sends her a few stamps and assures that her avocado plants are doing “MAGNIFICENTLY.”

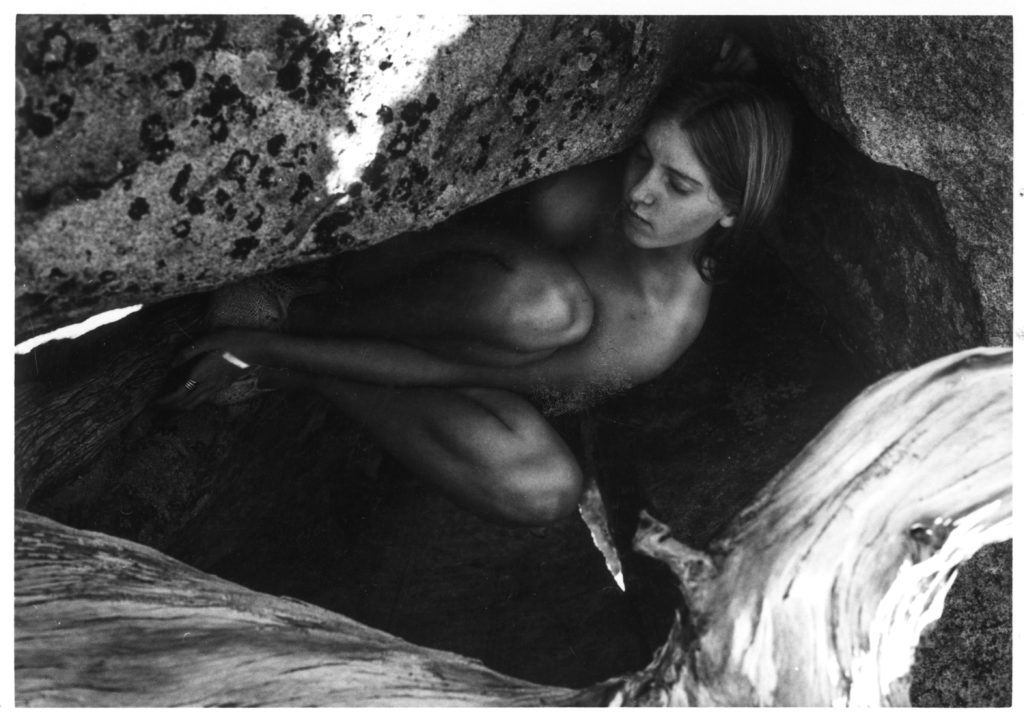

Woodman’s prints in Portrait of a Reputation show that she was already masterfully dealing in a gothic exploration of the human body that became the hallmark of her posthumously celebrated work. But these early prints are imperfect: smudged, off-center, over-exposed — traits not common in her later work.

“There are all of these errata in the production,” Abrams says. “To me, that’s what makes them so real and relatable. … I think the fact we’re seeing them not as flawless makes them that much more intriguing. This idea of Francesca Woodman as an artist for whom her feet never touched the ground, I don’t think that’s true. She was rigorous but she was also not perfect. In seeing the prints as they were made just widens that narrative a bit.”

Lange included photos he took of Woodman at her loft, capturing the haphazard way the young artist lived, the way she wrote on walls, the vintage clothing and secondhand furniture she employed in her photographs. The mess in her loft is indicative of her genius, but also perhaps of her tender age.

Portrait of a Reputation humanizes Francesca Woodman the individual, but it also celebrates the endless nuances of humanity. Each of us is more than meets the eye, we are more than the sum of our productivity. Over and over we try to apply straightforward narratives to people’s lives — not least of all artists — because it helps us make sense of a complicated world. It’s easy to understand Woodman’s suicide if she was a tortured, perfectionist workaholic; it’s more difficult to process when we see her as a silly, social young woman. But that’s the nature of suicide. It doesn’t make sense to those of us left behind.

But that’s just one interpretation, and one that Lange would likely find far too existential.

“I’m more interested in people understanding themselves [through Francesca],” he says. “We all have boxes in our lives, whether they’re physical boxes … [or] emotional boxes that we carry around. It takes a long time sometimes to open them, if we ever can. But the big gifts that are hidden in those boxes are powerful. And for me, opening up the Francesca box was connecting with her again, but also connecting through her with myself in a way that I couldn’t do before this.”

ON THE BILL: Francesca Woodman: Portrait of a Reputation. Museum of Contemporary Art Denver, 1485 Delgany St., Denver. Through April 5.