When Susanne Mitchell first traveled to Malawi in 1995, she found people very eager to share their thoughts.

“People were yelling out their opinions because they could,” Mitchell says over the phone from her home in Boulder. To meet her Malawian partner’s family, a 20-something Mitchell — fresh out of art school in California — had landed in one of the least developed nations in the world right as it was instating its first multi-party democracy after decades of English colonial rule, and then decades more of repressive autocracy under Hastings Banda.

“They could have dreadlocks, they could leave the country before they were 18, so there was all this stuff that happened at that time in Malawi,” Mitchell says. “I was quite young and naive… I didn’t know a lot. So it was kind of the beginning of this long process of understanding myself.”

Over the years, Mitchell has used her art to aid her exploration of race and privilege, often creating pieces that blend images and materials to highlight the legacy of colonialism in Malawi. Nonprofit art gallery east window (4949 Broadway, Unit 102-B) is currently displaying three of Mitchell’s works (inkjet prints mounted on aluminum) through Dec. 29.

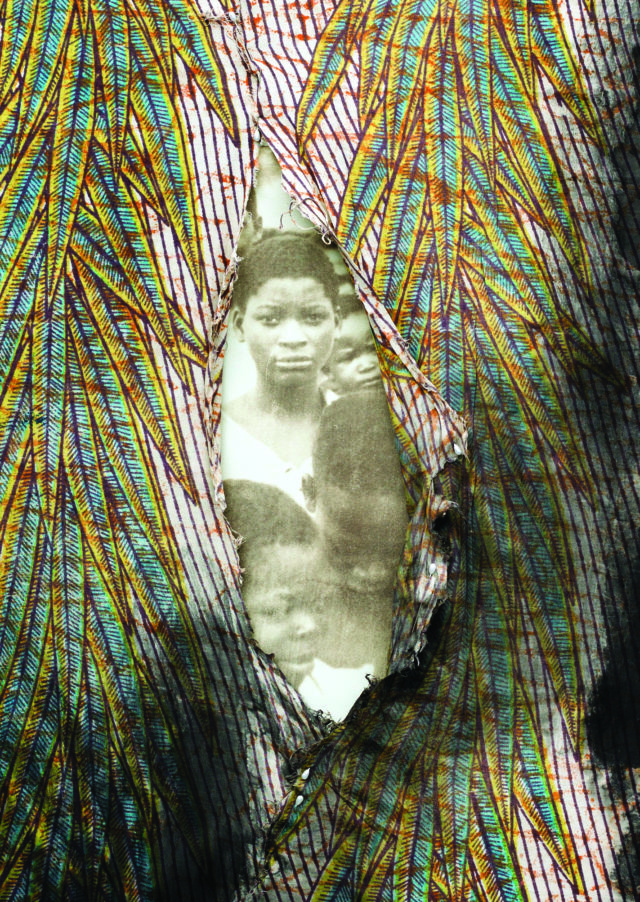

Mitchell’s work often uses a fabric called chitenge, used by Malawian women as clothing and for other domestic functions like swaddling babies or cleaning when the cloth begins to grow ragged. Drawn to the “life force” imbued in these common fabrics, Mitchell juxtaposes them with Victorian imagery, like furniture or French explorers, which emerge from tears in the fabric, offering a symbol of the effect colonialism has had on this landlocked East African country.

Mitchell says the recent movement to remove Confederate and colonial era monuments in the States made her revisit this particular selection of her work, which was originally made in 2012.

“I was a visiting artist at a studio in Cape Town, South Africa, in 2014 and 2015, when there was a movement where they started tearing down statues [associated with apartheid],” she says. “And so it was so interesting to see it start to happen here [in the United States] a few years later. It made me think about how, with my work, I always feel a little insecure or worried about it — whose story am I telling? And how am I telling it? And I think a lot about that, because I think it’s very important. But I feel like we all need to tell the stories. I think that everyone needs to tell these stories and they need to be told from multiple, different perspectives because we still have so far to go.”