The first thing you should know about the International Film Series (IFS) is that, when you go, you will watch your movie in peace. The IFS brooks no distractions during its screenings, and it tolerates no cell phones. This comes not in the form of those mildly passive-aggressive public service announcements that you see before showings at the theater — you know, the ones that tell you to put your phone in CineMode and kick back with a popcorn and soda. Rather, the IFS hires ushers who, if they see you on your phone, will tell you to your face to shut the damn thing off.

“If you go to any multiplex, you get that little thing that tells you to turn off your phones or whatever, but you know what that is?” asks Pablo Kjolseth, who’s run the IFS for 18 years. “That’s a Coca-Cola ad. No one wants to pay attention to a Coca-Cola ad.”

This is a part of the IFS’s rejection of the commercialism that pervades most of the movie industry, as is its policy on concessions — neither Kjolseth nor anyone else at the IFS cares if you sneak in food or drink — and its lack of trailers before showings.

“If you go to the multiplex right now, you’re bombarded with advertisements for the entire time that you sit there before the movie, and then you sit through 17 minutes of trailers,” Kjolseth says. “What it’s doing is it’s putting the emphasis on the consumerism, and that’s a distraction from the movie. At the IFS, we don’t have commercials, and we show the trailers while you’re sitting down, and we start the movie punctually.”

That’s what you get at the IFS, which will run from Feb. 2 to April 24 on the campus of the University of Colorado, as it has since 1941. All of this is conscious, and it feeds into the atmosphere and the viewing experience that Kjolseth tries to create, one in which you’re less of a viewer and more of an active participant.

Kjolseth has stocked the IFS with a combination of classics and premiers on a consistent schedule. Tuesdays are for documentaries, notably Janis: Little Girl Blue, an archival look at the life of Janis Joplin, and Frame by Frame, about the struggle to establish a free press in Afghanistan. Wednesdays are what Kjolseth calls “arthouse staples,” and have a diverse lineup that includes a 35mm print of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho; there’s also a restoration of Chimes at Midnight, Orson Welles’ reimagining of Shakespeare’s Henry IV and Henry V, that the director maintained was his best movie.

Thursdays are a film nerd’s dream — all restored 35mm film prints. These showings are an eclectic combination of car movies and old sci-fi flicks. There’s Repo Man and Highway Patrolman, both by former CU professor Alex Cox, a 3-D showing of Creature from the Black Lagoon and a presentation of Slaughterhouse-Five.

“As a medium, [film] deserves to exist, and the reason why is because film, at 24 frames per second, is engaging your mind at an active level because of the persistence of mind that requires you to sew together the images as they’re happening,” Kjolseth says. “You engage with it differently, and I’m trying to keep that experience alive.”

Fridays, Saturdays and Sundays showcase special events. The first three weekends in February are dedicated to Oscar-nominated short films — live-action the first weekend, then animated, then documentaries — and offer up a diverse lineup of unique stories.

After spring break, weekends are reserved for a retrospective on the German director Wim Wenders, with the IFS showing newly restored versions of many of his classics. Wenders personally supervised the restorations, which include hallmarks of New German Cinema such as Paris, Texas, Wings of Desire and Kings of the Road.

The IFS will also highlight some of Wenders’ films that were more obscure, or less acclaimed. There will be a showing of one of his earliest movies, The Goalie’s Anxiety at the Penalty Kick, which is a psychological detective thriller presented at a slow pace and full of soccer analogies. Also screening is Until the End of the World, perhaps Wenders’ biggest critical and commercial failure when it was first released in 1991. Wenders later revealed that his distributor made him cut out almost half of the movie to fit it to a length suitable for theatrical release. The restored version, the version that the IFS will screen, is an almost-five-hour-long director’s cut that Wenders says is the definitive version of his film.

“It was available,” Kjolseth says of his decision to highlight Wenders’ filmography. “It was recently, those restorations just happened. I routinely show restorations. This was something that was in the works for a while. There was a lot of people putting a lot of elbow grease into making it happen, and it finally did happen. They put out the word, and exhibitors, arthouse exhibitors such as myself, we just got in line.”

There’s something for everyone at the IFS. When asked if it was showing one essential, can’t-miss movie this year, Kjolseth laughed and pointed up and down the series’ large, busy playbill. For hardcore cinephiles, he says, Andrei Tarkovsky’s The Mirror may be a once-in-a-lifetime showing; Kjolseth is screening an incredibly rare 35mm print of the film, and this will probably be the last time he shows it.

“And then I could proceed to cheat your question a million different ways, pointing different people to different things depending on what their tastes are,” Kjolseth says with a laugh.

Your tastes might include Jafar Panahi’s Taxi, which highlights the power of film to connect people across cultures. The movie is a street-level portrait of life in Panahi’s native Tehran, and he filmed it on almost no budget, with nothing more than basic security cameras, despite the Iranian government placing him under house arrest and forbidding him from filmmaking for 20 years. Kjolseth believes that it’s more important than ever to show such a film to an American audience.

“All these superhero films that are basically, like franchises, it’s just companies that are making money off of toys. That does not feed your soul,” Kjolseth says. “But to be able to have a portal into another country, be it Iran, be it Germany, be it France, whatever, that’s where you can start to realize that we are all one. I think people who are so gung-ho to bomb Iraq, they have never seen a movie made by an Iraqi and looked into their world.”

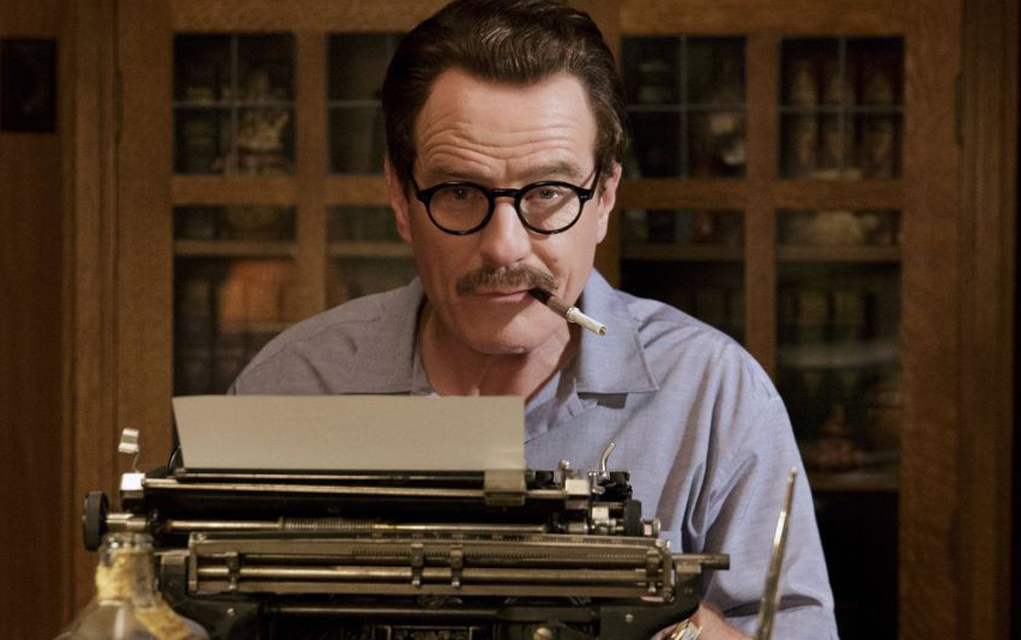

Other films have a different relevance, both to CU and beyond. Trumbo, the eponymous biopic of the former CU student and Hollywood screenwriter Dalton Trumbo, details his struggles against McCarthyism and his fight for free speech during the Hollywood blacklist of the 1940s and ’50s. Trumbo wrote many classic films, including Roman Holiday and Spartacus, but he was forced to work anonymously because of the blacklist. He became a symbol for courage in the face of oppression, so much so that CU named its campus’ designated free speech zone after him.

Edward Snowden is a symbol for free speech in a different way — freedom from unlawful spying and the hawkish eyes of our government. Snowden and Trumbo fought for the same thing in different ways, and both will be on display at the IFS. CitizenFour, the documentary of how Snowden revealed the NSA’s illegal surveillance program, will screen directly before he is scheduled to speak to CU students via video chat on Feb. 16.

“Free speech is an issue that never goes away,” Kjolseth says. “You always have to fight for it, and I think it helps if you have perspective, if you have history, and in a way, that provides you the twin engines of two monumental heroic figures who have put their own livelihood at stake to fight for free speech.”

Whatever the film, whatever its message, it’s there because it provides a unique viewing experience, one free of distractions — free of pauses, free of advertisements, mercifully free of cell phones. Watching a movie is a meditation, Kjolseth says, an uninterrupted, engaging experience that transports you to another world. Most cinemas will bombard you with commercials and branding, but at the IFS, there’s only you, the movie and what you make of it.