In the past decade, Video Station has saved my ass on many occasions. As a burgeoning film studies major at the University of Colorado Boulder, I made frequent trips there to pick up obscure titles my professors recommended or assigned for last minute homework. It’s been there for me in the days before Netflix and Hulu, when I immediately needed to see Richard Linklater’s Before Sunset after watching Before Sunrise. Also when I wanted to watch my favorite French film, Jeux d’enfants (Love Me If You Dare), during a romantic date night. For that rental, I ended up paying extensive late fees; totally worth it.

But the most significant, and admittedly most humiliating, occasion for which Video Station had my back was during a girls’ night with my best friend. On a whim we decided to watch It Takes Two, the Mary-Kate-and-Ashley-identity-switching classic, starring Steve Guttenberg and Kirstie Alley. Upon consulting all the streaming services at our disposal with no luck, a quick stop at Video Station and we came away with not only It Takes Two but also Passport to Paris, Billboard Dad and Holiday in Sun. While not my finest film-snob moment, it was a movie night with a best friend I’ll never forget.

When lamenting my fondest rental story to the store’s owner Bruce Shamma, he brushes off my embarrassment and tells me not to worry about it.

“I’ve learned long ago not to snicker at what people rent,” he says. “I wouldn’t have it in here if I didn’t want to rent it!”

Browsing the shelves of Video Station, there are very few titles they don’t want to rent. And my memories are only a few of the myriad that Boulderites have amassed over the 35-year life of this comprehensive neighborhood video store.

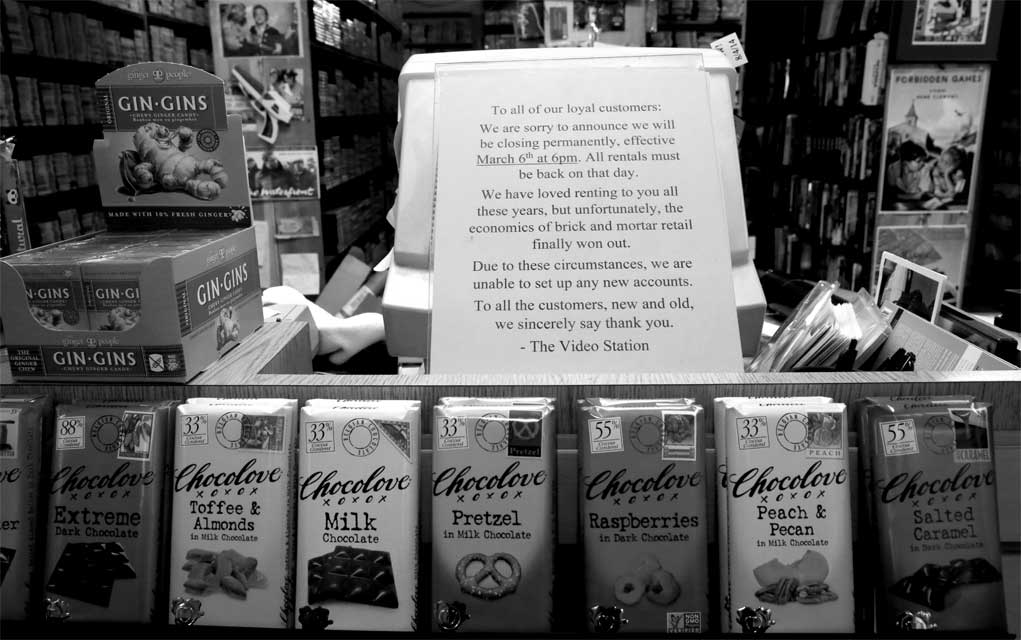

Serving as an essential piece of Boulder’s cultural landscape, Video Station sent ripples of disappointment through the community by closing up shop on March 6. While hardly surprising due to the current modern reliance on video streaming services, it was still a sad reality to cope with.

“To all our loyal customers: We are sorry to announce we will be closing permanently,” reads the sign posted on Video Station’s door. “We have loved renting to you all these years, but unfortunately the economics of brick and mortar retail finally won out. … To all the customers, new and old, we sincerely say thank you.”

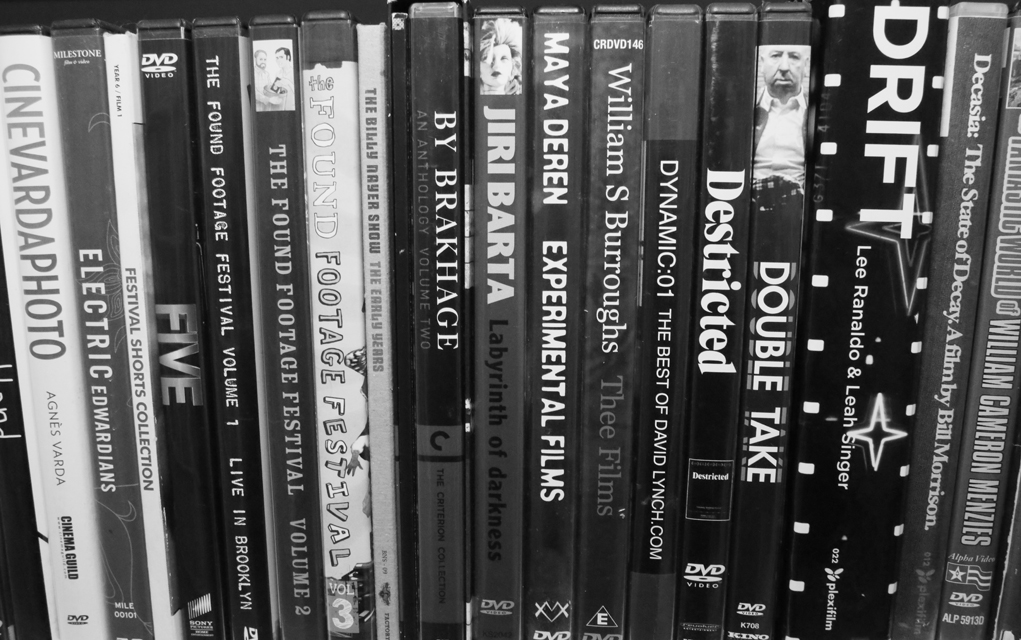

Scott Woodland and partner Ivory Curtis opened The Video Station in 1982. Just another video store in those days, it served as a thorough collection of everything and anything a movie lover wanted, going a few steps deeper than your average Blockbuster. More than just the big name movies and box office hits, it also welcomed the fringe titles, with a focus on niche genres including international, foreign, experimental, cult, silent and more.

Shamma took over the store in 2002. Sitting in his office, in front of movie posters from On the Waterfront and Django Unchained, he says he wanted to continue the legacy of carrying it all — from the eclectic to the esoteric.

“[The original owners] were completists to the same degree that I am. … Boulder is a wonderful advanced thinking place, where people have good taste and a lot of knowledge, especially about cultural things,” he says. “I just wanted to make sure I had those interesting obscure titles that I knew my clientele would always rent. I never reached that point where I thought, ‘I’d love to have that in the collection, but no one’s going to get it.”’

Video Station has a grand total of around 43,000 titles, which Shamma plans to hold on to for now. It’s more options than most video streamers and the sheer number of titles was one of the keys to the store’s long-time success. While many movies stick out over the years, staff guesses as to the most popular include The Big Lebowski or Lost in Translation. But some loose consensus puts Harold and Maude as the most-rented and most-purchased in the store’s history.

In the past, the store has garnered national attention such as in 2016 when the Wall Street Journal wrote the story “Revenge of the Video Store” about the local fight against online streaming.

This isn’t the first dying industry Shamma’s made a living in. He worked at Tower Records in San Francisco in the ’80s and then went on to own a record store for a decade. Before buying Video Station, he was the head buyer for the Virgin Megastore in Denver.

“It’s my second time around,” he says. “That was tough too. It’s exactly the same.”

But it was a different era in 2002, when Shamma took over.

“It was the heyday of video rental,” he says. “Lines out the door, multiple lines on weekends. Always busy to some degree, no matter day or night.”

He started to notice a steady decline in 2009. By then, multiple services were offering the joys of film on online platforms.

“At the beginning, when the decline started, I thought it would be manageable. It’ll go down a bit but then it will plateau. Well, I’m still waiting for the plateau,” Shamma says with a laugh.

Even up until a few weeks ago, Shamma remained optimistic, analyzing sales every day and comparing them to the past. While he says they still were signing up new members all the time, the flow wasn’t steady enough.

“It’s just the way the world is turning now, which is that the internet makes things so easy and convenient that it can be tough for people to decide against it,” he says. “I chock it all up to Netflix and streaming, the ease of just staying at home and pushing buttons.”

When Shamma announced the closing of the store in late February, floods of support came in from the community. Even in the final days, Shamma says he’s in no way bitter, but instead grateful for all the support he’s receiving.

“Because of my loyal customers, I’ll think about them and dream about them for the rest of my life I’m sure. I’ve got so many nice notes and emails,” he says. “And people are coming in just hanging out for a while.”

Everyone at Video Station expresses love toward their regulars who kept them in business for so long, says Robin Hyden, Shamma’s wife, who spoke with me on the store’s final day in business.

“It was just amazing. It made everything more bearable. We’re just going to miss being with these guys, and my husband will miss working with them too. Sorry,” Hayden says, tears flowing. “Someone gave me Kleenex,” she says reaching into her back pocket. “Yeah… sad day.”

Video Station’s crew includes some of the first people Shamma hired when he took over and a couple who were here even before.

“Everybody cares about movies here; nobody’s here to just make a buck,” Shamma says. “The sharing of knowledge, the friendship, it’s invaluable.”

Several of the staffers like David Shugert hail from CU and all feel fortunate to have nabbed a coveted position behind the counter. In the mid ’90s, Shugert was studying film and journalism with hopes of becoming a film critic, which he eventually did by writing reviews for Video Station’s newsletter. He started at the rental store part time, splitting his hours between there and Target.

“Even when I was a kid growing up in California, I would rent a lot of videos. I always thought it would be cool to work at a place like this,” he says. “They’ve seen a lot of employees come and go, but the turnover is probably not nearly as high as a place like Target.”

Joyce Gordon can attest to the low turnover rate, celebrating her 20th anniversary with the store last month. She cites the synergy between the team members as the magic of the store. Each comes with a different background, a different expertise, but the same passion for film.

“I’ve loved film since I was a child growing up in Chicago, going to the Clark Theater with my grandma,” Gordon says. “All of the ladies would come in hair rollers, smoking cigarettes in the movie theater. That’s how old I am!”

Not only did movie fans work the cash registers, quite a few moviemakers did as well. Video Station employed many young talents, including Derek Cianfrance, who went on to direct films including Blue Valentine and The Place Beyond the Pines.

“[Cianfrance] used to work here when I was first hired,” Gordon says. “He was working on his student project at the time, and I used to tease him that he would have to give me extra special thanks [in his film credits] because I was filling in for his shifts.”

The store has served as inspiration for many, including former employee Brock DeShane. In the ’90s DeShane was attending CU and working the register, but then left to pursue acting, writing and directing.

“We were all going to school, making films, and working at the Video Station was part of that,” DeShane says. “It was just a great library and repository of information that fed us, that fed our souls and our imagination.”

Because who can forget one of the best perks of being an employee?

“Free movies, free movies, free movies. Oh, and the free movies,” Shugert says.

During his tenure, Shugert would grab stacks of films over the weekend, from just a couple new releases to upwards of 10 titles when needing to brush up on some classics or strange offerings. When asked if any titles pop out over the years, his answer is a little surprising.

“Mighty Joe Young, the 1998 version with Bill Paxton and Charlize Theron. It was PG, and we could play it in the store,” Shugert says. “I think I played it a few days in a row, unknowingly, and a former employee was like, ‘Didn’t you just play that?’”

One of Gordon’s memories includes a car smashing into the front window of the store in the late ’90s and the following clean up of broken bookshelves and DVDs scattered on the floor. She also remembers monthly meetings from the early days on the job.

“We had movie quizzes where the owner, Scott Woodland, would describe the movie and we would have to come up with the title,” she says. “There would always be that threat if you didn’t do well on your movie quiz.”

“The movie quizzes! I forgot about that,” Shugert interjects.

Reminiscing about private rituals and inside jokes, the team agrees there are some stories just too sacred to share.

“No, we can’t talk about that,” Gordon says, with other staffers nodding in agreement.

She describes her two decades behind the counter as totally rich. Even though she’s had more “professional” jobs, she says, this one was special.

“This has been my most valuable experience, because with each transaction you get to see a slice of life,” Gordon says. “To be able to relate to the vast variety of customers is so enriching and such a challenge and so wonderful. Not to mention the movie selection, the great wealth of titles we have.”

She goes on to compliment the trove, listing her favorite genres until a customer and her daughter stop by her register. With flowers and a card for the staff, the customer expresses her thanks and well wishes, and Gordon comes from behind the counter for hugs and final goodbyes.

With returning patrons and the same faces at the registers, the Video Station experience surpasses mere movie renting.

“I’ll miss the long-term customers,” Shugert says. “Those who’ve been coming here for a while. I looked forward to that every week. It’s like family almost.”

And with two decades at the Video Station, Shugert says he’s also seen more than one of his favorite customers pass away. He recalls an older couple who would frequent the store, the husband John, an ex-policeman from New York and the wife Billie, who Shugert had only spoken with on the phone yet still cultivated a relationship with.

“I got to know her,” Shugert says. “She would remember my birthday, and she’d send me cards, which was so sweet.”

Shugert remembers one day running into the couple near the store’s old location.

“It was after John had a heart operation, and I hadn’t seen him in a bit. I was walking out of Safeway, when we were on 28th. I saw him, and with him was this smaller woman. The second she talked, I knew who she was, and I gave her a big hug… I get a little teary just thinking about it,” he says, and then pauses.

“She passed away first, she was about 70, and then he went a couple years later. But yeah… it’s just connections like that.”

For decades, Video Station retained that reputation of bringing people together.

“There’s a real neighborhood feel,” says staffer Noah Arnold, who came on at the store in 2002. “Everybody knows everybody. It’s like Cheers but with movies.

“I’ve seen more people reunite here than I’ve seen any place else, where it’s just sort of random,” he continues. “Like, ‘Oh my god, you rent movies too! We haven’t seen each other in years.’ I always thought that was great. As much as we rent movies, it’s also a place to hang out.”

In the scary reality of the modern world, community hangouts are fast becoming scarce. As the world becomes more automated and local treasures fall to the giants, one can only wonder what is lost in the ether.

“If you want to talk to a human being you’re out of luck now,” Shamma says. “How do you browse if you just want to look at possibilities without something in mind already? What if you want to see 200 new releases within inches of each other? Or how about holding it up to the guy at the counter, ‘What do you think of this one? Has anyone seen this one? Any good feedback?’ Now, it’s just an algorithm telling you. What’s the pleasure in that?”

And for some, those electronic formulas are far from replacing the real thing.

“The algorithms don’t work for me. I’m insulted by some of the stuff Amazon says I’m supposed to like. I’m just like, ‘Are you fucking kidding me?’” Hyden says. “I’m the generation that goes to record stores and goes to bookstores and places like this still. It’s hard adjusting to the world.

“Beautiful things have to end sometimes, at least that’s what I’m told,” she continues. “I’m always like, ‘Why can’t the crappy corporations end?’”

Hyden, who met Shamma when they worked at Tower Records together, now works at the Chez Artiste as a manager and projectionist. She knows all too well about the threat of technology and corporations.

“I found something I was really good at, splicing and manipulating film. Then it went away,” she says. “I really don’t like computers, I feel like my soul’s being sucked out, and now I do it all on computer. It’s a hard world for our generation.

“When people would ask, ‘So what do you guys do now?’, [Shamma and I] always used to say, ‘Oh, we own another dying technology,’” she says with a laugh. “But who knows? Maybe one day it’ll be cool again.”

There aren’t many future plans among the employees. For the next few weeks, they’ll be boxing up the collection and moving it out. While the end looms, the staff leaves in good spirits.

“[Video Station in 1997] was the last interview I had, so I’m a little rusty,” Shugert jokes. “So we’ll see what I can do after this!”

In the wake of its closing, the store leaves behind a community of movie lovers who will surely miss their friendly neighborhood video store.

“It’s a true legacy for Boulder, and I think it’s the sort of place that will be legend,” DeShane says. “But it lives on. That’s what happens with art. It lives on in people, and people spread that. So closing the doors doesn’t close the door on the inspiration it had or the legacy it leaves.”

As a fitting goodbye for a place and group of people with no idea what the future holds, the Video Station looked to wise time traveler Doc Brown for their final tweet on their last day: “This is the end of the line folks, ‘Roads? Where we’re going, we don’t need roads.’”