A cross far too many stretches of our movie-going lives, we see movie after movie without seeing one that really moves. At once stealthy and breathlessly paced, The Social Network scoots at a fabulous clip, depicting how its version of Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg made his billions, and, according to various allegations and two key depositions, whom Zuckerberg aced out of those billions, while following his digital yellow brick road. Is director David Fincher’s film the stuff of greatness? Not quite. But the picture is very, very good.

Fincher and screenwriter Aaron Sorkin do not, at first, appear to be a match made in heaven. Sorkin is relentlessly verbal, Fincher fastidiously pictorial. The meticulous, sinister mise-en-scene Fincher brought to Seven, Fight Club and Zodiac informs the atmosphere here, albeit in a subtler way. (The musical score by Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross insinuates on the sly, making Zuckerberg’s ambition the stuff of emptiness looking for fulfillment.) The worlds we see on screen, primarily Harvard University a few years ago and the sweaty, sunny dot.com Palo Alto, Calif. landscape a little more recently, feel — deliberately — as remote and exotic as anything in Fincher’s The Curious Case of Benjamin Button.

The movie begins with a nine-minute doozy of a scene, a one-act play, really, set in a noisy Cambridge, Mass., bar. The boy-man destined to create Facebook is about to get dumped. Harvard undergrad Zuckerberg, played as an exquisitely ambiguous riddle by Jesse Eisenberg, sits across a table from his girlfriend (Rooney Mara). The motormouth we hear in action, as Mark patronizes her non-Harvard self, bears out her characterization of him as “exhausting.” The scene ends with her delivery of the thesis line: “You’re probably going to be a very successful computer person.” Then she calls him an a-hole. The note is struck; the film’s challenge, met with impressive confidence and very few audience concessions, is to make the central figure interesting without falling prey to cheap plays for our sympathy.

Is director David Fincher’s film the stuff of greatness? Not quite. But the picture is very, very good.

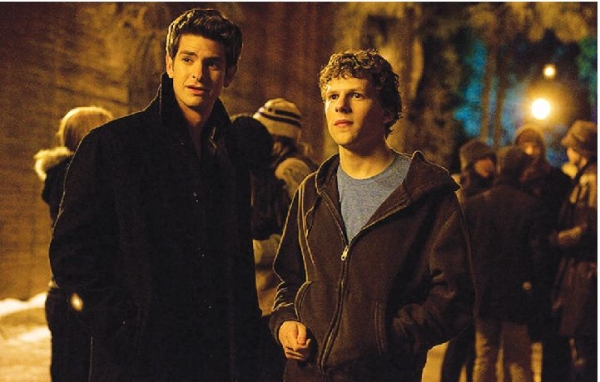

That night, drunk, Zuckerberg blogs about his ex, and in short order he hacks into the university’s system to download female students’ pictures as part of a “Who’s hot? Who’s not?” voting game. Zuckerberg’s techno-acumen assured, he’s asked by the identical twins and future Olympic rowers Tyler and Cameron Winklevoss (Armie Hammer playing both parts) to help create a Harvard-focused social networking site. On the downlow, Zuckerberg takes his mad programming skills elsewhere and, with financial help from Zuckerberg’s classmate Eduardo (Andrew Garfield, the film’s sympathetic conscience) something called “thefacebook” is born. The first scene’s prophecy becomes truth. Did Zuckerberg steal someone else’s idea? His line on that, in one deposition scene: “They came to me with an idea; I had a better one.”

Justin Timberlake portrays Napster co-founder Sean Parker, who gets in on the Facebook action and entices Zuckerberg with promises of billions, not to mention women, wine, song and drugs (though Zuckerberg’s more or less disinterested in all that; he lives to code). Timberlake is excellent at these sorts of bad boys. As good as Eisenberg and Garfield are, Timberlake is likely to attract the most attention. He is Zuckerberg’s siren, the father figure (not much older than Zuckerberg) who crows, “Private behavior is a relic of a time gone by!” in between cocaine-induced flights of paranoia.

Does the film play fast and loose with the facts? Yes. Most biopics do, and this isn’t even a conventional biopic. And that’s why it feels like something different. Its tone is rueful, skeptical, bittersweet. Sorkin’s facility with dialogue prevents the portentous visual quality from sitting on everything too heavily. Shot on digital video, the movie’s beautiful, as lighted in shadowy, oak-paneled tones by cinematographer Jeff Cronenweth, but Harvard looks terrifyingly insular — like Hogwarts without the camaraderie.

Sorkin’s script owes a debt to his (unproduced) screenplay “The Farnsworth Invention,” which he later adapted for the stage. In that piece, a tantalizing new development in communications technology — television — becomes a battle for supremacy between a man with an idea, and a man with an idea of how to exploit it. Right down to its deft and multiple storytelling viewpoints, The Social Network works much the same ground. The people here aren’t larger than life; they’re so consumed by the project, and the speed at which it takes off, they become its servants, even as the money rolls in and the friendships run aground.

“People talk about Mark’s borderline Asperger’s, his horrific PR style, but I think that Facebook required someone with those kind of limited social skills,” Fincher has said. That’s the easy paradox of The Social Network: Antisocial geek creates globally popular social networking site, appealing to both social and antisocial types alike. One choice Sorkin line stays with me. “We lived on farms; then we lived in cities; and now we’re going to live on the Internet.” Gleeful overstatement, phrased just so. The movies were made for that sort of talk, and an unlikely marriage of directorial and writerly sensibilities has produced one of the most stimulating films of the year.

Respond: [email protected]