Comfort watching comes in all shapes in sizes. Sometimes it’s a chubby little cubby all stuffed with fluff. Other times it’s Gene Kelly dancing with an umbrella and splashing around in puddles. Diversion, you could call it: A moment of pure cotton candy. It zaps you with sugary sweetness, wipes the blues away and makes you hum a little ditty.

But diversions work best in small doses. Like a sugar high, they’re difficult to sustain, and too much will leave you feeling sicker than when you started.

You’ve probably watched plenty of comfort movies in the past two months. And they’ve helped with the initial shock of losing your job, losing your friends, maybe even losing a loved one to the dreaded virus. They put a smile on your face while the news put the fear of god into you. They brought sunshine through the screen while cold, wet snow covered freshly bloomed tulips. And for a while, it worked. But the power of comfort films has weakened. Kelly can prance in those puddles all he wants, but the blues are here to stay.

The time has come for something else, something that doesn’t divert your emotions but embraces them. You want to empathize with characters who are going through what you’re going through, surviving the struggles you’re surviving, and asking the deep, difficult questions keeping you up at night.

You need existential cinema.

Lucky for you, foreign and art house films are loaded to the gills with existential ennui. From fears of individual erasure to planetary annihilation, these movies look for meanings behind meaninglessness, the fluidity of right and wrong, and the celebration of the individual. Here are four to get you going, but there’s plenty more out there if you’re hungry.

High and Low Though most point to Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard as the progenitor of existentialism, the movement wouldn’t have made it half as far if not for novelist Fyodor Dostoyevsky. Between each page of prose, you can feel Dostoyevsky wrestling with his desire to be a moral man in a world littered with immoral attractions and addictions. Add highly structured tales of cause and effect, the ever-present element of chance, and it’s no wonder filmmakers have been drawn to his work.

King among them: Japanese filmmaker Akira Kurosawa, who counted the Russian as one of his primary influences. And few of Kurosawa’s films wear Dostoyevsky on its sleeve like High and Low, an acute criticism between the disparity of the haves, the have nots, the have lesses and the have nothings. It’s like walking in a strange city without a map: You have no idea where you’re headed, what’s around the next corner, and where the touristy part of the city ends, and the red light district begins. By the time the steel curtain falls, you’ll never look at the world the same again. Streaming on The Criterion Channel and Kanopy.

The Trial Based on a novel by Franz Kafka, The Trail is filmmaker Orson Welles at his most Wellesian. Anthony Perkins stars as K, a man accused of a crime he neither committed nor comprehends. K can ask all the questions he wants, but only riddles come back. Welles stacks the deck through the majesty of set design: Doors dwarf K while ceilings close in on him. Hallways offering escape extend into the infinite. And just when he thinks he’s making headway, another government official steps out of nowhere to block him. It’s like K’s trying to run a marathon through a tub of glue. Welles thought it was one of his best, and he might be right. Streaming on Kanopy.

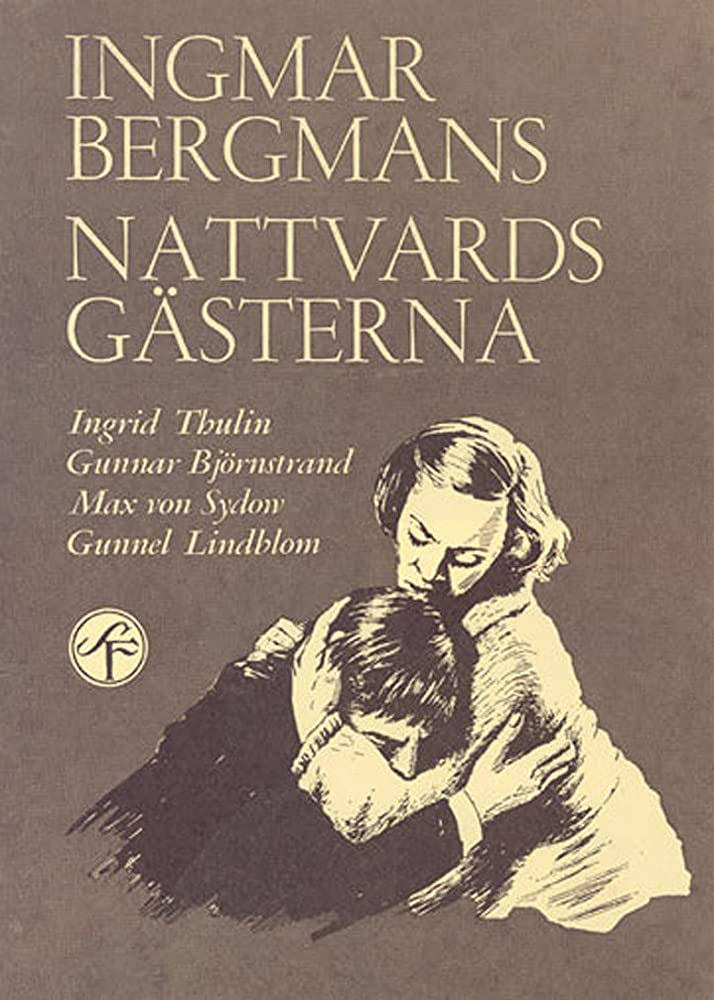

Winter Light The second installment in Swedish filmmaker Ingmar Bergman’s unofficial trilogy (Through a Glass Darkly, Winter Light, The Silence) is by far the best. Pastor Tomas (Gunnar Björnstrand) has misplaced his faith. He’s not sure where, and he’s not sure he wants to find it. Märta (Ingrid Thulin) loves Tomas, but he does not reciprocate. So, she waits and bears his silence and his cruelty. Then Jonas (Max von Sydow) enters and confesses to Tomas — he lives in fear. The atomic bomb will destroy everything, obliterate existence and erase man from the universe. What, then, is the point? Tomas has no response, and it costs him dearly. Sounds bleak, doesn’t it? It is, but the trick of Bergman is that he finds his way from god’s silence to Tomas’s despair to Molly Bloom’s heart going like mad announcing affirmations in triplicate without an ounce of comprise or concession. Streaming on The Criterion Channel and Kanopy.

First Reformed You could pick any movie from Paul Schrader’s oeuvre and find healthy doses of existentialism, but First Reformed might be his most fully formed. Continuing the conversation Bergman started in Winter Light, Schrader tosses in a dash of Travis Bickle — arguably the most Dostoyevskyian character this side of Notes from the Underground — and updates the crisis from atomic to ecology. Streaming on Amazon Prime, Hoopla and Kanopy.