Growing up partly on the Turtle Mountain Indian Reservation in North Dakota, Jerilyn DeCoteau was often puzzled by the rigid and disciplinary way her mother ran the household.

“She used to say things like, ‘I’ll make you kneel on a broomstick,’ or ‘I’ll wash your mouth out with soap.’ You know: ‘I’ll make you scrub the floors with a toothbrush,’” she recalls. “I don’t think we really understood where that came from, except we knew that at some point she had been in boarding schools.”

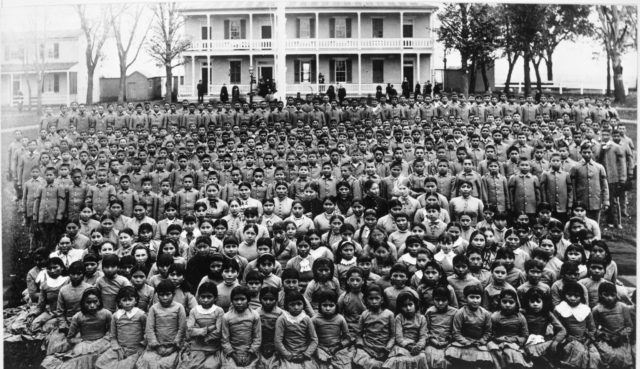

For Indigenous children in the 19th and 20th centuries, these residential programs run by the federal government were a far cry from the camaraderie, prestige and privilege typically associated with the innocuous term “boarding school.”

“This was so completely the opposite of that,” says DeCoteau, an enrolled member of Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians. “These places were less about education, and more about forced assimilation.”

Since Ellis Island became a symbol for immigrants looking to build a life in the “New World,” the mythology of the United States has centered on the idea of E pluribus unum: “Out of many, one.” But for the first peoples who established sovereign nations on these lands, that process of becoming one wasn’t a choice — and for many, the price of assimilation was paid in abuse, trauma and even death.

As Captain Richard Henry Pratt said during an 1892 speech in Denver, the mission of these federal boarding schools — whose operators took children from their families, replacing their tribal traditions with forced learning of English, Anglo culture and Christian dogma — was disturbingly simple: “Kill the Indian in him, and save the man.”

Colorado was home to five such boarding schools, from the Grand Junction Indian School on the Western Slope to the Good Shepherd Industrial School in Denver. Another was located on the grounds of Fort Lewis outside Durango, where History Colorado researchers are now conducting a state-mandated examination of the site after mass graves were discovered last year at similar residential schools in Canada.

As former board president of the National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition and a former attorney with the Boulder-based Native American Rights Fund, DeCoteau has dedicated her professional life to the uplift of Indigenous people, including the excavation of this dark and misunderstood chapter of American life.

“There was so much silence around it,” she says. “That was kind of a hidden part of our family history, and a hidden part of Native history.”

‘Not even past’

That once-hidden history, not fully understood by DeCoteau until after her mother’s death from breast cancer at age 47, will meet the light during a screening of the 2021 film Home from School: The Children of Carlisle at the Museum of Boulder on Thursday, Sept. 22.

The documentary by director Geoffrey O’Gara centers on the Carlisle Industrial School in southeastern Pennsylvania, the nation’s flagship Native boarding institution, where hundreds of children died over the course of its 39 operating years.

Among the Carlisle victims were three Northern Arapahoe boys — Horse, Little Chief and Little Plume — whose remains were repatriated in 2017 by a delegation of tribal citizens from Wyoming. Home from School is the story of their journey from the Cowboy State to the Keystone State, taking viewers into the beating heart of this still-raw history and the efforts to heal intergenerational trauma.

“It’s a film that can really change and deepen people’s understanding of the facets of violence of colonialism,” says Emily Zinn, education director at the Museum of Boulder. “For people who don’t have an understanding of the concept of cultural genocide, I think they will carry this story with them for the rest of their lives.”

To help unpack those heavy concepts, DeCoteau — a new member of the Museum of Boulder Board of Directors — will be joined in a post-screening conversation by the film’s associate producer Jordan Dresser, chairman of the Northern Arapaho Tribe, a guest curator and longtime collaborator with the museum.

“Our work as a historic society is really about forging strong, inclusive and engaged citizenship,” Zinn says. “And there’s no better way to do that than [by working] in service of repair with the communities and individuals who have been disenfranchised, and against whom violence has been committed, in order to live the lives we live in Boulder today.”

For DeCoteau, whose own family history sports the bruises of the forced assimilation at the heart of Home from School, the film and resulting conversation is an opportunity for the public to explore how the violence of settler colonialism remains baked into public life in America — and how we might begin to affect change.

“It’s still very much in our institutions and our way of thinking,” she says. “I don’t know how you undo all the damage. But some of it definitely needs to be undone.”

ON SCREEN: Home from School: The Children of Carlisle (SOLD OUT). 6 p.m. Thursday, Sept. 22, Museum of Boulder, 2205 Broadway. The film is also streaming free on-demand through the Kanopy online video platform with your Boulder Public Library card.