Like it or not, artists change. Though we wish to preserve them in amber, those we hold near and dear grow into individuals that we may not necessarily want, but certainly may need. That was the case with Charlie Chaplin, who in 1918 — merely four years after his inauspicious debut — was one of cinema’s biggest comedic stars.

With his shabby appearance, baggy trousers, oversized shoes and dusty bowler hat, Chaplin’s Tramp character was the very image of refinery and hilarity. His short comedies were a sensation, and they quickly made him one of the most recognizable individuals in the world.

However, Chaplin wanted more. He already had complete control over his movies — which he wrote, produced, directed, starred, edited and, eventually, composed — and his own, personal studio in Hollywood offered him the ability to work endlessly on his projects. But it still wasn’t enough. Chaplin wanted to say something deeper, and he knew comedy alone wouldn’t cut it. He needed drama. Those around him warned against mixing sentiment and slapstick, but Chaplin knew better. And when he set eyes on young Jackie Coogan, a 5-year-old vaudevillian, Chaplin knew he struck gold. Here was the co-star he needed for his first feature-length film: The Kid.

The Kid opens on an unwed mother (Edna Purviance, a long-time Chaplin co-star) leaving a charity hospital with her baby. She has no means to raise the child and through a series of ridiculous, but hilarious, contrivances, the small bundle ends up in the Tramp’s lap. Thankfully, the Tramp’s heart is big, and he takes the child in. Jump five years later, and the Kid (Coogan) lives arm in arm with the Tramp. Their home is impoverished, but it is filled with love.

Chaplin claimed that, “Life is a tragedy when seen in close-up, but a comedy in long-shot.” And The Kid is quite possibly the best example of this aphorism. Many of the comedic scenes take place in wide shot with the Tramp or the Kid perfectly framed in the center while other characters circle around them, best illustrated in the back alley brawl between the Tramp and a bully (Charles Reisner).

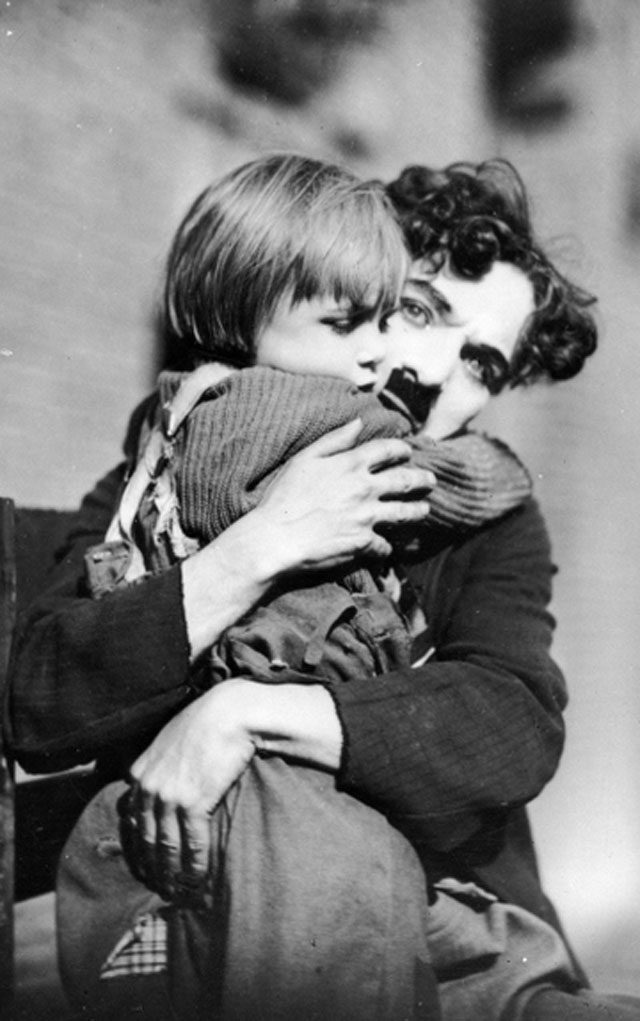

Later, a welfare officer (Frank Campeau), feeling that the Kid would be better off in an orphanage, tears him from the Tramp’s home. Here, Chaplin moves in close and provides one of the most gripping and heart rending moments in all of silent cinema. By cutting from the Kid pleading to be returned to the Tramp, and the Tramp physically restrained in his home, Chaplin tugs at the audience’s heartstrings until they almost snap. The Tramp even stares directly into the camera, further pleading with the audience to stop this injustice.

If there was any doubt in the audience’s mind that Chaplin would forever be confined to comedy, it evaporated immediately with those two shots. Ninety-five years later, their power hasn’t dwindled one iota. Woe to those who thought Chaplin was just another silent clown. Artists grow. How lucky we are for that.

On the Bill: The Kid and the preceding short, “A Dog’s Life,” accompanied by Hank Troy on the piano. 7:30 p.m. Wednesday, July 20, Chautauqua Auditorium, 900 Baseline Road, Boulder, 303-442-3282, chautauqua.com/events/film/. Tickets start at $6.