Before I knew Juliet Wittman as a writer — as acclaimed theater critic, investigative journalist, food writing professor and author — I knew her as an eater. I first met her on the back side of a mini-cupcake stand at the Boulder Farmers Market where I worked, knowing nothing of the woman except for the way she ate a cupcake. One of our first regulars, she would come to the booth every Saturday morning and order one or two small delights, eating each with eyes closed, in two precise bites.

Most people ate the cupcakes as an amuse-bouche, tackling the whole thing all at once. Others like me, would eat each in three smaller bites — two of cake leading up to a shockingly sweet mouthful of icing. Juliet, though, was a rare two-bitter, using the first to get to know the food, the second to both study and savor it until her full-mouthed mmm’s turned to small talk, weaving food into the stuff of everyday life.

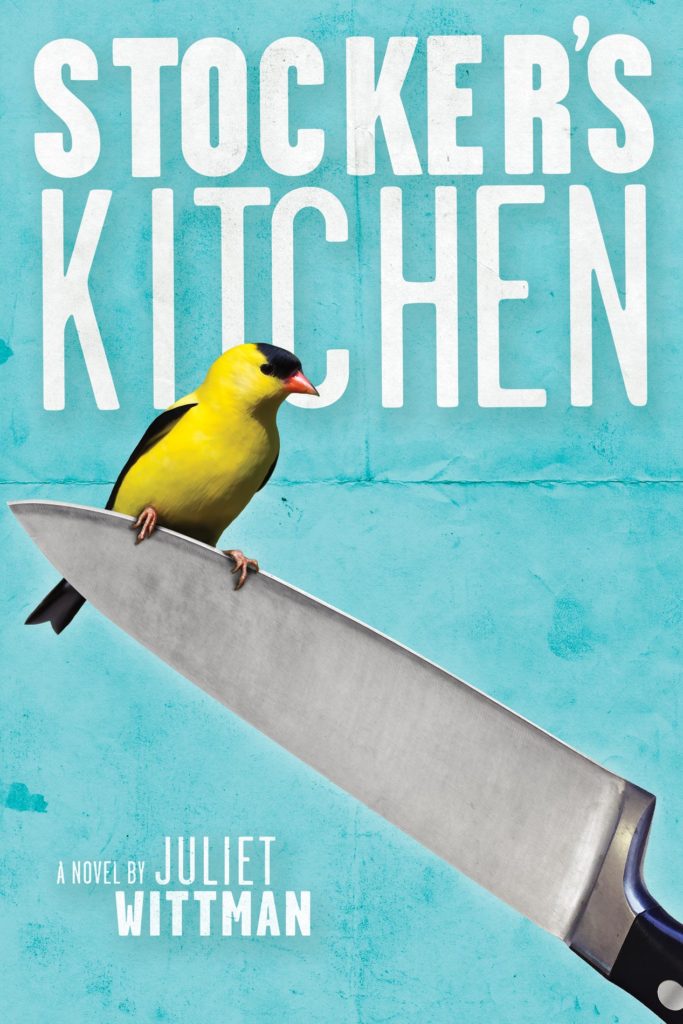

Eight years later these early memories are as potent as ever as I arrive at Juliet’s house to interview her about her new novel, Stocker’s Kitchen, a book about the intimate power of food, not written by a chef, but simply by a woman who loves to cook and eat.

The moment I step into her house I swear I can smell something cooking, but save for a lone can of coconut milk on the counter, there’s no food in sight. There are cookbooks scattered about, a few opened to recipes for coconut curry, but Juliet assures me nothing’s in progress, at least not yet. Settling into the dining room for our interview, I’m left wondering if I’m still under the aromatic seduction of her book, so rich in its descriptions of food that at one point while reading I pushed the pages to my nose, convinced they smelled of braised rabbit.

Stocker’s Kitchen, to be released on Jan. 25, is about the book’s namesake restaurant, acclaimed by trendy New Yorkers for its food that is a “fierce dark mixing of elements,” likewise present in the characters who make up Stocker’s world. At the helm is Stocker himself, a white chef who’s as good at his job as he is at being racist, sexist and classist, and in Juliet’s words, “not a good person at all.”

Reading the book, he was not always the character I wanted him to be, let alone the one I’d expect a Jewish immigrant woman to write about, “but still he’s a real person,” Juliet tells me. It’s a funny thing to say because he’s not. Stocker is a fictional character — one Juliet stumbled across accidentally in a writing prompt, but one she feels she was destined to write. He’s a complicated schmuck who finds redemption in food. Deep down, Juliet wondered how it was possible for someone who is not a good person to create food that could transfigure those who ate it and so transform our idea of the cook.

The book’s narrative arc traces Stocker’s call to his higher self, a transcendence prompted by a love story that begins with him yelling at a strange girl in the dark alleyway behind his kitchen:

“Hey. Hey girl, You … You hungry?”

He couldn’t have said anything better, Juliet says, “she’s as hungry a soul as Stocker is,” and he speaks to her in food — the language of the appetite. So, as the two fall in love, it’s love his food speaks.

Stocker begins cooking for Angela, and his food changes. His new dishes are filled with a coruscating energy, almost roaring with life. It’s all there, the rejoicing, the nourishment, the songs of the small green frogs courting their mates in the velvet darkness of a spring night. If his pastas could leap from their plates and caper, they would; the small parcels of fried dough he likes to fill with savory surprises are so buoyed by the heated deliciousness within that they almost need to be weighted down. The green energy of herbs prick through his entrees. It’s as if he is taking the foods apart, freeing the molecules and allowing the air between to vibrate. No one could say how he does it, but to eat these things is to feel a rush of joy, a sense that life has never been so full, the heart rising, breath quickening, memories unanchoring themselves from nooks and crannies of the brain and standing forth with startling clarity.

When we first started talking, Juliet swore she had nothing in common with her main character, and in terms of virtue that’s true. But along the way she retracts and says, “I guess we both want something elemental in food.”

For Juliet, lover and writer of stories, food is the ultimate tale. A vehicle for memory, a keeper of tradition, she sees food with a poetic appreciation that’s realized in Stocker, who touts cooking as anthropologically important. To transform food with fire is what makes us human, à la the philosophies of Richard Wrangham as espoused in his book, Catching Fire, which claims that societies and communities started around the fire, with people sharing food with goodwill. Stocker certainly believes that; for him, all food seems to be served as if it were the Eucharist.

When asked how food connects her to her sense of family and community, Juliet pauses, closes her eyes, and begins to talk of early memories of her mother:

“I was born in London in 1942 when the war was on and the bombs were falling. My parents were refugees. The food situation was fairly dire — there wasn’t that much food around but, my mother, my mother, she could always feed people. If you gave her a chicken and some rice she could make something delicious.”

For Juliet, food is magical — a container and metaphor for memory and tradition. It allows her, and her character Stocker, to transcend time. And just like the feast her mother magically made from a chicken and a cup of rice, the food in Stocker’s Kitchen is equally surreal. Not the kind of cuisine to be preserved in cookbooks, but the kind that lives somewhere between the page and the imagination, the imagination and the heart. It’s a feast for the reader’s soul.