Known as “the third genius,” Harold Lloyd did not have the same background in vaudeville as Charlie Chaplin or Buster Keaton; yet, he ended up making more movies than both of them combined. Lloyd started his career as a Chaplin knockoff, but when director Hal Roach saw him as a background performer wearing round-rimmed glasses without lenses, he saw a new character. Lloyd remembers it differently, but no matter, Lloyd and those glasses became synonymous; a cinematic legacy was cemented.

As his Glasses character grew in popularity (he was second to only Chaplin in box-office receipts), Lloyd’s films became more gag- and stunt-centric. It didn’t matter if he was a store clerk trying to drum up business by scaling a skyscraper or a footballer trying to score the winning touchdown, Lloyd’s characters constantly found themselves in scrapes. They always found a way to win — usually, the hardest — and with a “go-getter” attitude that became emblematic of the 1920s. The war to end all wars had been fought and won, the ’20s were roaring and Lloyd’s characters, full of pluck and mettle, could always be found at the center.

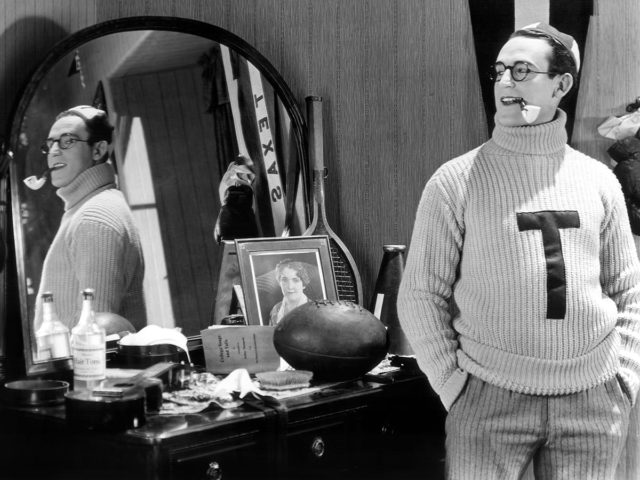

Historian Kevin Brownlow describes this as “desperation to get somewhere and be somebody.” With Lloyd, the somewhere and somebody are intertwined. In one of his best films, The Freshman, Lloyd — here, Harold Lamb — wants to become a gregarious man about town like his two idols: the college football captain and Lester Laurel, a fictitious movie star Lamb models himself after. The where: Tate University, the perfect college for an Anytown, U.S.A. But the real “somewhere” Lamb/Lloyd is desperate to get to is the goal line on the football field. To do so, Lamb will have to overcome obstacles both at Tate — pranksters, soused tailors and a disapproving dean — and on the field. And once he crosses that line, he wins the big game, society accepts him into the fold and Tate won’t just celebrate Lamb, it’ll model itself after him.

It’s no spoiler to reveal Lamb wins the game and gets the girl. Unlike Chaplin or Keaton, Lloyd’s characters always hit their mark. The audience loved Lloyd, and Lloyd loved them back.

Movies are both timeless and of a time. The fervor surrounding collegiate loyalty and football still exists. People still want to fit in, and audiences still like to see the good guy win. But The Freshman is also very much a product of the 1920s. Few filmmakers capture the era in which they made their movies like Lloyd, but The Freshman pulls together all the energy and excitement of 1925, the absurdity of Prohibition (and how easy it was to come by a drink) and gives us plenty of archival images of the streets and cities where Lloyd set his story. Watching the movie is like time traveling while sitting still. Even better, it’s still a fun ride today.