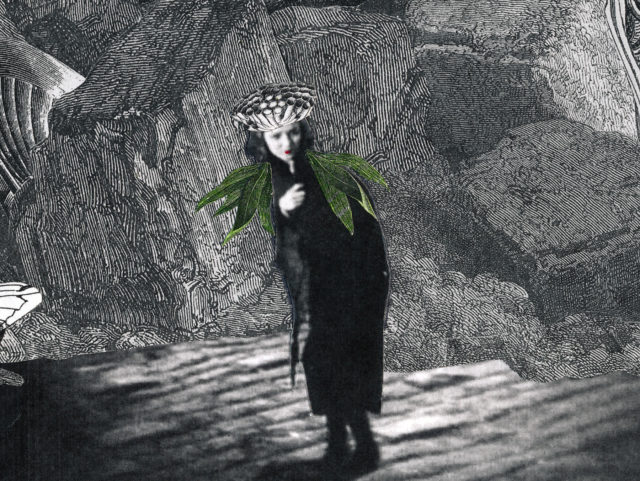

Stacey Steers’ films are far from straightforward. She uses collage to stitch together found imagery like Victorian illustrations and silent movie heroines to create a loose narrative. The films are textured and sensual, evoking an ominous feeling — bugs crawl throughout the frame, vials of red blood stand stark against black and white pictures, characters interact with each other — all set to a haunting soundtrack. It’s unclear how everything’s related, yet, the end result is a film that feels almost like a dream, maybe sometimes like a nightmare

“I like these dark spaces,” Steers says. “They feel very dreamlike, very nighttime in a positive way — the places that you can go that aren’t a part of the mundane reality of daily living. It’s imaginative space essentially, and that’s a world that I enjoy being in.”

Now at MCA Denver, Steers’ latest film, Edge of Alchemy, is playing along with an exhibit featuring some of Steers’ sculptures and collages that appear in it. Edge of Alchemy (2017) is the third film in a loosely related trilogy that includes Night Hunter (2011) and Phantom Canyon (2006).

Steers studied fine art with an emphasis on film at the University of Colorado Boulder, where she has been an adjunct professor in the film department since the early ’90s. Steers started in animation and then turned to collage in the next decade as a way to push her films into new territory.

To make her collages, Steers pulls from illustrations, woodcuts and engravings, mostly from the 19th century. She uses what she’s inspired by and what’s available, which she says tends to be “creepier” animals like insects, bats and snakes, which all feature prominently in her films.

For the characters in her first collage film, Steers used Eadweard Muybridge’s Human and Animal Locomotion series that was published in 1887 and features thousands of photos of figures in motion. For her following two films, Steers used scenes featuring silent film actresses Lillian Gish, Mary Pickford and Janet Gaynor. Her source material helps Steers with the emotional landscape she tries to convey.

“I’m definitely looking at the whole spectrum if I can. I’m not trying to sugarcoat experience,” she says. “And that’s often another thing: Silent films do have a lot of darkness. There’s a lot of pathos, which is one of the reasons that the characters are fun to use because they had to express all that in their faces.”

Steers’ films are made up of thousands of collages, each second made up of eight or so. She calls it a good day when she can complete 25 collages — which ultimately amounts to about three seconds of footage. The films take roughly five years to complete.

None of Steers’ films have a concrete narrative. The trajectory of each is guided by her impulses. When making Night Hunter, she realized her heroine was slowly turning into a bird. Steers then had to adjust the film to create a build-up to this notion, which alluded to themes like transformation that she could then follow more consciously.

“People say Night Hunter is a really dark film, but for me it wasn’t really,” she says. “She was just living through a transition she doesn’t understand but she has to accept. And to some degree, I was thinking about physical changes that you just can’t stop, and you just have to figure out how to live with them.”

In Edge of Alchemy, Steers pursued the themes of creation, science and restoration. In the film, Mary Pickford’s character lives in a barren landscape full of dead bees, and then she creates Janet Gaynor as her own Frankensteinian creature, who then brings life back to the desolate world.

In all her films, Steers displays the interiority of women’s lives and emotions. She examines desire and what that leads her characters to do.

“The women in my film — they’re yearning for something; they’re looking for something,” she says. “Often that initial motivation ends up taking them in the place where the outcome is not what they would have predicted and … it sets in motion a sequence of events where they have to figure out how to respond and how to relate.”

By keeping her stories loose, Steers invites endless interpretation. MCA curator Zoe Larkins sees more political messages in Steers’ films. In Edge of Alchemy, Larkins notes environmentalism and an exploration of gender roles.

“There are no male figures in the film, [and yet] she’s able to produce life on her own, seemingly without influence from anything male,” Larkins says. “I love the narrative. It’s very righteous.”

Larkins detects hints of Alice in Wonderland and H.G. Wells in the films, plus a connection to early surrealist filmmaking — all inspirations that Steers didn’t consciously use.

As the name of her film suggests, Steers performs a sort of alchemy in her work. By blending together a series of images she concocts a numinous elixir. The final effect of the potion is up to the viewer when they take a sip.

ON THE BILL: Stacey Steers: ‘Edge of Alchemy.’ MCA Denver, 1485 Delgany St., Denver. Through April 5.