![[A Camel for the Son] Alima Hassan Abdullai-brother Mahmoud 300dpi](https://archives.boulderweekly.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/A-Camel-for-the-Son-Alima-Hassan-Abdullai-brother-Mahmoud-300dpi-640x840.jpg)

Each person in Fazal Sheikh’s photography has a story of survival. The men, women and children have persevered through wars, refugee camps, abuse, social stigmas and more. They look directly into the camera, asking the viewer to see them and hear their story.

“They’re engaging me, I’m engaging them,” Sheikh says. “And by extension then they’re also engaging the viewer, implicating the viewer in a kind of relationship.”

Now showing at the Denver Art Museum through Nov. 12, Common Ground covers Sheikh’s work from the past three decades. His portfolio includes photos from refugee camps and feeding centers, exploring topics like human trafficking, death and domestic violence. The images come from around the world; from townships in South Africa, to asylum centers in Amsterdam, to the holy city of Vrindavan in India, where widows ostracized from society seek sanctuary.

Sheikh initially started his journey in Kenya. His father was from Nairobi, and Sheikh was interested in learning more about his heritage. While there, his aesthetic began to emerge.

“I had never worked in photojournalism,” Sheikh says. “I realized that struck a chord with my own sensibilities, those political/social issues and the aesthetic.

“It’s interesting to insist upon the idea that all of these areas of interest — the realm of art, the realm of politics, social issues, documentary — have kind of [crossed] over,” he continues. “That was always somehow a priority for me.”

Sheikh received a Fulbright fellowship to spend a year in Kenya, during which, half a million refugees flooded the country. A camp was located in a remote desert region near the border of Sudan, housing 25,000 of those refugees, half of whom were unaccompanied minors.

“It was my first experience [in a refugee camp], and I was fairly overwhelmed about the sheer magnitude of the problems and the number of the people there,” he says. “But I soon realized the way forward was to maybe ask members of the community to collaborate with me and help me document the essence of what they were experiencing.”

This became the foundation of Sheikh’s work. Never wanting to impose or trespass, Sheikh spends long periods of time in communities, getting to know the people he photographs. And even though he’s been doing this for decades, Sheikh enters every project with an open mind. He never assumes he understands the problems other people face, so he lets the individuals help shape his work.

“That’s the kind of mode I’ve carried on with most of my projects, this idea of arriving at a place with not a very clear sense of what one wishes to produce,” he says. “But [I go] with a kind of openness for listening to what priorities the community has at hand. Then I somehow slowly begin to etch out a kind of voice that is a mingling of that which is my own and that of which is born of the perspective of the community.”

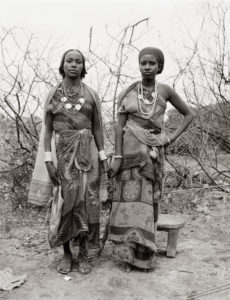

Right: Abshiro Aden Mohammed, Women’s Leader, Somali Refugee Camp, Dagahaley, Kenya, 2000, from the series A Camel for the Son. Fazal Sheikh

Sheikh gives the people in his photos control of the image. He doesn’t attempt to craft a particular idea, but instead lets the person choose how they want to be presented. It results in a collaboration that produces rich, organic photos.

Sheikh captures an intimacy in his portraits, even in works where there is no eye contact.

Behind the many expressionless faces are lives filled with tragedy, and through connecting with the photo, the viewer can gain some understanding of what it’s like to live in embattled communities.

As with most of Sheikh’s work, Common Ground presents photos in black and white.

“Early on I felt I saw in black and white,” he says. “It reduces things, to a much more centered and considered realm; it removes the immediate seduction of color. It reduces the formal aspects of the gaze and precision to, I think, a more contemplative zone.”

The portraits in the exhibit are complemented by Sheikh’s landscape work. They give context to the people in the show, illustrating the backdrops of these people’s lives, be it a refugee camp or a war-torn village. Landscapes, he says, also can function as a sort of portrait.

“There can be something intimate in the rendering of a landscape,” Sheikh says. “The landscape holds beneath the surface something that is similar to what a sitter in a portrait holds behind the landscape of their face or alluded to on the surface but that we can’t immediately access.”

After his early work in Africa, Sheikh continued exploring his heritage. He went to visit his grandfather’s birthplace in what was then India but has been Pakistan since 1947. Sheikh never met his grandfather but grew up hearing stories of his legacy as an entrepreneur and philanthropist.

While learning more about his roots, Sheikh also met with Afghan refugees, who were exiled from their homeland during the Afghan-Soviet war. For his subsequent work, titled The Victor Weeps, Sheikh blended his own narratives with those of the refugees, who told stories of loss and enduring hope.

“Going from that onward, I wasn’t always looking directly at the notion of heritage, but I was looking at things that seem to resonate with me. That seemed in some instances to be regions that my family might have emigrated,” he says. “And more broadly I was interested in challenging the idea of moving beyond racial boundaries, gender boundaries, religious boundaries and the possibility of making work that isn’t about segregation but is about collaboration and communication.”

For instance, in Common Ground, Sheikh tells the story of a Muslim woman and a Hindu woman who had lost daughters to dowry violence but banded together and created a shelter for victims of domestic abuse.

Despite the time he devotes to meeting the communities he photographs, Sheikh struggles with how to properly represent the people in his photos. He strives to respect their individual voices and stories to avoid casting them solely as victims of their situation.

“In the Somali context, there was this idea that for many of the Somali women, if they’ve been assaulted they’re completely ostracized within that society,” he says. “So the aspect of having their testimony taken formed a kind of new catharsis, but also a realization that they were resisting and not being confined to that one traumatic thing in their life.

“Those kinds of things are particularly difficult,” he continues. “[I try] to represent trauma in a way that isn’t sensationalized, which honors the voice, and which you hope makes people think differently not only about those women but also what they’ve been through.”

Sheikh’s overall goal with his work is to start a dialogue. He wants his work to add more to the discourse to give people greater awareness.

“Often I’m interested in spaces and issues that have not been rendered in a way that I feel is broad and all-encompassing,” he says. “I hope that by making these projects we can broaden our vocabulary about certain issues.”

Sheikh doesn’t necessarily consider his work an act of social justice. He prefers not to confine the work to that label, but instead to let it function on multiple levels. He just hopes it strikes a chord with the viewer, whether it be a humanitarian or an art lover.

With his photos, Sheikh focuses on documentation, not necessarily fixing the problem.

“The temptation in photojournalism is to rant about how one thinks they’re going to change the world with their pictures. I don’t particularly believe in that,” Sheikh says. “What we can take solace in is the notion that by working and offering a conversation, that furthers the discussion. That’s the thing I hold on to.”

Sheikh says starting a dialogue is particularly important now in regards to the current political climate, which he says demonizes immigrants. He says it’s vital to stay open-minded and be receptive to what immigrant and refugee communities have to offer.

“Look at what’s happening in our country right now and our inability to think generously and openly about other religions and other nations,” he says. “People fled under extreme duress seeking sanctuary and are willing and able to dedicate themselves to working for their new country. I think we’re losing a sense of value that is offered to us by these groups that come.

“[We need] not to reduce them to this xenophobic idea that people from certain countries are terrorists or a threat to our people, our nation, our values,” he continues. “I find that so deeply unsettling and so ungracious.”

The stories in Common Ground vary, but similarities emerge. We all strive to meet our basic needs for food, shelter and safety; we hope to raise our families and make the best of the cards we are dealt. Common Ground tells the stories of survival and perseverance, and it reminds the viewer that we’re not all so different.

“It’s important to me that we have the sense that any of us, given the wrong circumstances, could find ourselves in exactly that position,” Sheikh says.

By stirring a sense of understanding through his work, Sheikh hopes he can pave the way for a better future.

“Much of the work in that exhibit was made 20 years ago. Some of those issues have been resolved and people have returned home,” he says. “And maybe there’s some sort of benefit into looking back and attending to history in a way that might challenge the way we look at our present and instruct the way we think about our future.”

On the Bill: Common Ground: Photographs By Fazal Sheikh, 1989-2013. Denver Art Museum, Hamilton Building, 100 W. 14th Ave. Parkway, Denver. Through Nov. 12.