In 1989, a jury found Brent Brents, then 18, guilty of raping two children. He spent the next 15 years in jail, and when he got out in July 2004, he went on a terrifying rampage, raping and assaulting dozens of men, women and children until his capture in February 2005.

He mainly victimized prostitutes, but he went after other targets as well, including a woman alone in her apartment in Denver and a grandmother and her twin grandchildren in a house next to Denver’s Cheesman Park. After police captured him, Brents guessed that he had raped about 60 men, women and children during the seven months he was out of prison. Judges from various jurisdictions sentenced him to a total of 1,509 years in prison — and that was only for crimes committed against 12 victims.

After his capture, local media scrambled to get angles, fighting each other for interviews with Brents, his family and his victims. But for reasons unknown, Brents chose only one journalist with whom to share his story: (now former) Denver Post reporter Amy Herdy.

Herdy tells her side of her strange, unsettling relationship with the serial rapist in her book, Diary of a Predator. It’s a true crime retelling of Brents’ story, but it’s also what Herdy calls a “dual memoir.” It’s both the story of Brents’ horrific childhood as well as an intensely personal, revealing look at Herdy’s role as the journalist telling his story, and the effect it wrought on her and her family. She describes the book in the prologue as “the tale of two predators — one a criminal, the other a journalist.”

~ ~ ~

Shortly after Brents got out of jail, he started dating a woman who had an 8-year-old son. Something about him didn’t sit right with the woman’s family, though, and they soon discovered Brents was a convicted pedophile. The woman asked her son if Brents had ever molested him. To her horror, the boy said yes. She told Aurora police, who asked Brents to come in for an interview on Nov. 23, 2004. To the surprise of the police, he did, and he told an Aurora detective that yes, he did molest the boy.

But in what can only be described as an act of incompetence, police didn’t arrest Brents, but sent him on his way to roam freely about Denver. It wasn’t until Jan. 26, 2005, that police issued a warrant.

Herdy enters the story here. After Aurora police announced the warrant, she was one of five Post reporters whose job it was to cold-call Brents’ possible family members in Fort Smith, Ark., and beg for a comment.

She wasn’t successful, nor were her colleagues. But the Post’s competitor, the now-dead Rocky Mountain News, was.

“If we want to get these people to talk to us, we’re not going to get them from a newsroom in Denver,” she told her editor. “Someone needs to show up on their doorstep in Fort Smith.”

Of course, Herdy’s editors chose her for the job, and she ended up scoring an interview with Brents’ mother and sister. By the time she returned to Colorado, Brents had been caught.

Herdy’s assignment shifted: interview Brents. She sent him a handwritten letter asking for an interview, and she mentioned she had spoken with his family.

He called her a few days later, and he said the only reason he did so was that she had spoken with his mother and sister. Then he asked her a key question, a question that built the foundation for the their future correspondence.

“Everybody says they hate me, that I’m a monster,” he asked Herdy. “Do you think so?” “I think you’ve done monstrous things, but I don’t consider you a monster,” Herdy replied. “It’s not my place to judge anybody.”

~ ~ ~

From then on out, Herdy had exclusive access to Brents.

“To me, he was just another subject, to be afforded the same considerations as everybody else,” Herdy says in a coffee shop in Louisville. “I treated him the same that I did every other interview.”

By the time she started working on the Brents story, Herdy had already established herself as a top crime reporter. She and Post reporter Miles Moffeit were Pulitzer finalists for a 2003 series called “Betrayal in the Ranks,” an in- depth look at how few sexual assaults in the military ever get prosecuted. She had written the piece entirely from the perspective of the victims, and to her, Brents represented a chance to come full circle: write about sexual assaults from the side of the perpetrator, not the victim.

Brents opened up to Herdy completely, allowing her to pick his brain and sending her letter after revealing letter, detailing his attacks as well as a childhood filled with being sexually abused.

His letters, many of which Herdy prints in full in the book, are meticulously detailed and make for tough reads.

“He writes in a narrative fashion, which is very unusual,” she says. “He has a penchant for detail, which you could argue is because he’s a psychopath.”

As Herdy plunged deeper, Brents began to adopt a more and more familiar tone, calling her pet names like “Rockstar” and ending his letters with “Ly” — an acronym for “love you.” He began talking about their “friendship.”

“He was focusing in on me with his laser-like predator vision, noticing every detail,” Herdy says. “He once [told me], ‘I enjoy the clean smell of your letters.’”

She was disgusted, but she pressed on. She didn’t know why, at first.

“This was a case that caused me tons of personal conflict,” Herdy says. “My husband asked me to walk away, but I wouldn’t. Do you know how hard that is on a marriage?”

Fortunately, Herdy says, her marriage emerged stronger from the experience.

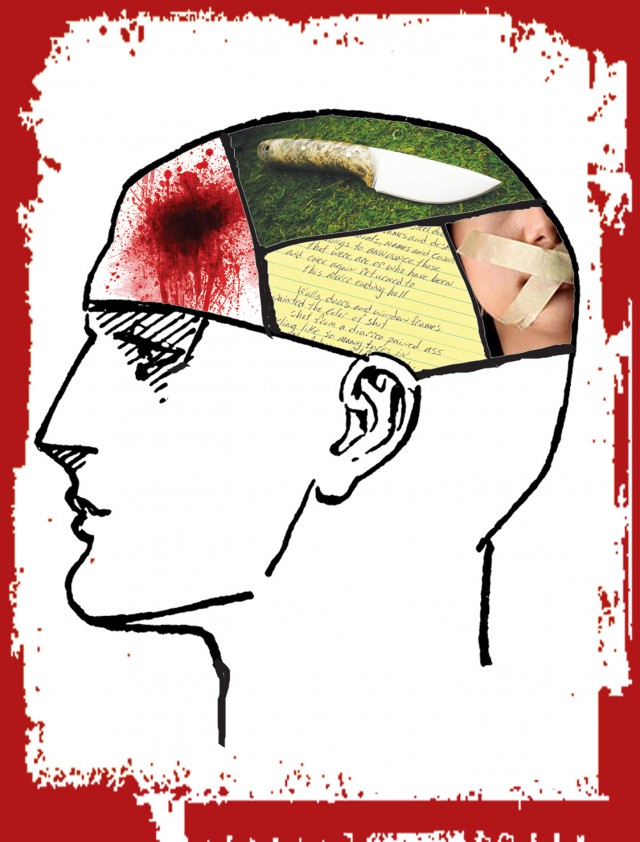

In her book, Herdy goes into deep detail about why Brents’ story was so compelling for her. Talking to Brents, as it turns out, flushed out some of Herdy’s emotional trauma from her own childhood involving her parents and her brother. She began to see parallels between her situation and Brents’.

The more she corresponded with him, the more she began to feel an unwelcome sentiment: empathy. Try as she might, she couldn’t hate him, which puzzled her and eventually alienated her from the Post newsroom. She insisted that her editors treat Brents with rights afforded to others: privacy, confidentiality, off-the-record sanctity. After an editor opened a letter from him without her permission, she set up a P.O. box and told Brents to send her letters there.

“The irony wasn’t lost on me: I was protecting a serial rapist from my editors,” Herdy writes. “I just didn’t trust them anymore.”

~ ~ ~

Reading the book, one comes away with an understanding of what made Brent Brents, the smiling, bright-eyed first grader, into Brent Brents, serial rapist and pedophile. This is probably by design, since in the first pages of the book, Herdy includes a description of Brents assaulting a child, followed immediately by one of Brents’ journal entries in which he describes how he was raped by both his parents starting at the age of 4.

Brents claims that he is sorry for his crimes. And it’s not like he has anything to gain by saying so — he’ll be in jail for the rest of his life regardless. It was logistically impossible to reach Brents by deadline for this story, but Herdy offered to help. She suspected Brents might call her before Boulder Weekly’s deadline, and she offered to take some questions to Brents and relay Brent’s answers back to Boulder Weekly. Though a departure from traditional journalism, BW took Herdy up on her offer. These are the answers Herdy says Brents gave her, edited for punctuation and style:

Boulder Weekly: Are you a victim?

Brent Brents: No. At one point I was but not anymore. I stopped being a victim a long time ago. I made the choices to do what I did. There’s nobody to blame but me.

BW: Would your life be different if you had a different upbringing?

BB: Had I had more normal parents I probably would be different.

BW: Do you still feel the need to be sexually violent?

BB: The thoughts have crossed my mind. I struggle. I hate myself for having them, and the medication takes the physical part away.

BW: Why Amy?

BB: [He starts out answering directly to Herdy.] You weren’t trying to fuck me over or manipulate me or pay me. I felt like I could trust her the most. I believed in her. What can I say — it’s destiny.

BW: Are you remorseful?

BB: Yeah, you know I think for a while I was self-centered and cry baby about it. But as time goes on, and the more I learn about friendship, I’m starting to fill up with remorse for what I did.

You never forget those people you hurt.

~ ~ ~

It’s a dilemma anyone who has ever dealt with a pathological liar in their life is intimately familiar with: How do you know if said liar is telling the truth? Promises of redemption, of remorse, are easily spoken, but you can’t help but wonder: How would I know if they are telling the truth? Herdy thinks Brents is genuinely remorseful, though she thinks he wasn’t always that way.

Another woman who corresponds with him, “Ellen,” also thinks he is genuinely remorseful. Ellen began writing Brents after her daughter died in a drunk driving crash. A devout Catholic, she felt spiritually empty after her daughter’s funeral. Inspired by Mother Teresa’s diaries, she believed that if she prayed for someone who had no one else to pray for him or her, she might regain some meaning in her life. God pointed her to Brents, she believes, and she eventually began praying for him and writing him. To her surprise, he wrote back, and they have been corresponding ever since. She writes, “he became a brother to me — a very good brother.”

“Brent is a different person than who he was eight years ago,” she writes in an email. She continues, “On a positive note, and this is very much a personal thought of my own without any proof whatsoever, I believe Brent has proved something. People can change. A person incapable of love can learn to love … a person incapable of compassion can learn to feel compassion. This does not mean that Brent is capable of living in society; he is not. But Brent does have redeeming value as a person and as a child of God.”

~ ~ ~

The response to the book so far has been overwhelmingly positive, Herdy says. She tells the story of a neighbor she didn’t know very well who came up to her and threw her arms around her, thanking her. Readers write her and thank her for delving so deeply into the “why” aspect of Brent Brents. A film director, Kevin Lewis, contacted her about turning Diary of a Predator into a movie, and Herdy recently finished the first draft of the screenplay.

Lewis says he was intrigued by the portrayal of Brents. People have a tendency to see the world in black and white, he says, but the beauty is in the grey.

“There’s never been a movie about a rapist. When I talk to people about a serial rapist, people kind of cringe. It’s funny, people seem to see a serial rapist differently than they see a serial killer,” Lewis says.

“I’m really excited to get going with it and work on it. I really think that people need to know about the story, and I think it might give them a different perspective. We always vilify these people, and at the end it’s not just black and white. There’s a lot going on that we just discount.”

~ ~ ~

The experience of writing a book, of exposing one’s self to horrifying stories of rape and sexual torture, begs some questions: Why? How could anything positive come from the story of Brent Brents?

Herdy’s somewhat baffling response is that the experience of knowing a serial rapist has been a positive one for her. She doesn’t consider Brents a friend, per se, but she says she has at times acted like a friend to him, and him to her.

“Someone like him is supposed to mess up your life, crush anyone that comes into his path,” Herdy says. “Surprisingly, knowing him changed my life for the better.

“[Before I met him] I was in a really cynical place in my career, and it awakened some compassion and empathy in me that I had feared was dead. … Once you start treating yourself with compassion, it spills out into the rest of the world.”

Editor’s note: David Accomazzo took a reporting class from Amy Herdy when he was a student at the University of Colorado Boulder.

Clarification: A previous version of this article stated that Brents estimated he had raped 60 men, women and children in his lifetime. In fact, he guessed he raped 60 people during the seven months he was out of jail. During his lifetime, he guessed the total was in the hundreds.

Amy Herdy will discuss Diary of a Predator at the Boulder Book Store on Tuesday, Jan. 17. Starts at 7:30 p.m. 1107 Pearl St., Boulder, 303-447-2074.