In the summer of 1871, America was celebrating its 95th birthday and the recent acquisition of more territories due to the Mexican-American War. Manifest destiny fever was high in the new nation, fueled by rampant coverage about the possibilities of these vast lands. Millions viewed and ogled over the images of jagged geological formations, rivers snaking through towering canyons and endless dust horizons.

But only a select few were actually out in the Southwest experiencing it. Timothy H. O’Sullivan was one of those lucky men, although it may have not seemed like luck, since the adventure wasn’t easy.

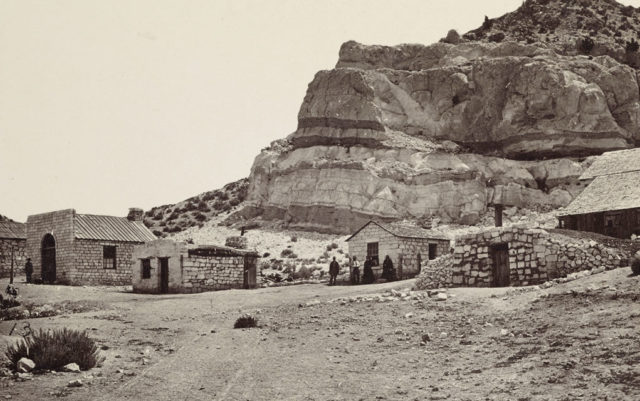

He traveled with his camera and his portable darkroom for hundreds of miles with some of the region’s first explorers. While the commanders closely graphed and mapped the topography, O’Sullivan became the eyes of the group, employed by the government to photographically document it.

The result of his work is a series of prints that were some of the first to ever give a glimpse of the West to those back on the inhabited coast. A few dozen of the photos, along with those of fellow photographer William H. Bell, taken over four summers during the informally coined Wheeler Survey, are on display through January in On Desert Time at the Denver Art Museum (DAM).

As the quintessential pioneers of Western photography, there was no guidebook or guidelines on how to do it. O’Sullivan and Bell, who was O’Sullivan’s substitute on the survey in 1872, found that taking pictures in the harsh, barren space with no prior depiction or narration was unlike any project they had done before.

“They had no precedent so there was a degree of surprise and difficulty,” says Eric Paddock, curator of photography at the DAM. “These are artists trying to figure out how to depict lands in climates that are completely foreign to them. They were trained in the Northeast so all the traditions and techniques they were taught and accustomed to favored lush landscapes. They were really mentally and visually unprepared for this.”

Which is not to say they weren’t professionally prepared. Both photographers apprenticed at studios in New England before moving onto military-related photography jobs. O’Sullivan took now-famous photos of the grizzly and harrowingly still aftermath of the Civil War battlefields; Bell was commissioned by the Army Medical Museum to take portraits and photograph wounds.

While completely unrelated to the landscape work from On Desert Time, Paddock thinks those experiences unconventionally prepared them for what they were up against out West.

“If you spend three years taking photos of dead bodies, graves and war, there’s got to be something calming about coming to vast emptiness and unspoiled possibility,” he says.

While both captured the same region and had the same blank canvas to work with, their finished products turned out differently both visually and emotionally.

O’Sullivan’s photos are encompassing, usually wide expansive shots of an entire scene. Bell’s are often zoomed in and skewed, with pointed illustrative details.

“With O’Sullivan, you look at the parts: the sky, the rocks, the water, and you mentally assemble where you are. Bell does the opposite, taking the structure of those elements and trying to make a puzzle,” Paddock says.

It’s a juxtaposition that works well within the exhibit. Both approaches are artistic in the compositional techniques used to achieve the desired essence. These men took in the unfamiliar setting in creatively contrasting ways and each achieved a depth and focus that worked for what they were trying to capture.

“These [approaches] really show the differences in attitudes toward the environment,” he says. “It’s intriguing.”

A staple of O’Sullivan’s work is a cloudless sky that holds a sharp contrast to the etched rocks of the canyons. Since the materials used during the camera exposure were sensitive to blue color, Paddock says, the skies were most likely faded and O’Sullivan manipulated the negatives to make them completely blank. Shots with rivers or lakes have a similar smoothing effect, with the water almost looking like a shiny sheet of brass.

Dramatic and scattered lighting in Bell’s work give the photos a cluttered and disorienting feeling. The jolted perspective makes the piece seem lifelike and immediate, “like you could fall right into the frame,” Paddock says. “It reminds me of Frederic Church’s ‘Niagra’ [painting].”

In the gallery, Bell’s shots are arranged to provide an interactive feel. Each picture is presented in the order he took them, lurching from one exposure point to the next, like a flipbook ostensibly climbing through the cavern crevices.

But actually capturing these rocky, dry surfaces wasn’t an easy task. The technique they used, called dry plating, is an arduous process complicated by the sweltering desert climate.

There was less than a five-minute window to coat a glass plate with collodion, place it into the camera frame, adjust the aperture, expose it for a half-second and then hurry to develop the negative. O’Sullivan had to make do with a do-it-yourself darkroom in a converted army ambulance. It was an obvious challenge from the comforts of a studio, as he was constantly lugging 100-plus pounds of equipment around to get the perfect shot.

By the end of the excursions the men had a couple hundred negatives. Some of the plates were ruined by dust or lost in transit. Those that made it back to Washington, D.C. were printed on albumen and widely dispersed as a sort of propaganda tool.

“These were highly influential at the time,” Paddock says. “They spoke to people’s curiosity of expansion and travel.”

All major media ran weekly stories featuring engravings of O’Sullivan and Bell’s pictures, and some of their best shots were used in Congress as an ode to the survey’s progress when asking for an annual budget for the next summers.

After the prints circulated, some critics credited the grandeur solely to the nature itself, calling the photographic skill involved “unromantic” and uncreative. Paddock says those opinions, usually directed toward O’Sullivan’s more composed and even work, make him laugh because they were written by city folk who had no concept of the environment’s context.

“The last 25 years there’s been an ongoing debate in the art world on how to understand and interpret his work,” he explains. “I see the work of someone who is learning to love the landscape as he goes. [These pictures] are about emptiness. Places like these, he is seeking a kind of silence, finding new energy and peace.”

Now, as people snake through the collection of photos, they take in O’Sullivan’s broad scenes and Bell’s specified images, appreciating a black-and-white take on lands we are familiar with. But at the time, these were the blueprints of a place that everyone talked about but few would ever see firsthand.

On the Bill: On Desert Time. Denver Art Museum, 100 W. 14th Ave. Parkway, Denver, 720-865-5000. Through Jan. 8, 2017.