Even art enthusiasts who believed they knew the work of leading American abstract expressionist Clyfford Still had surprises waiting when the museum of his work opened in Denver. But for everyone else, it was a surprise just knowing the man existed at all.

What reputation preceded him was that of an elitist who hid his work away. At a time when Still was being recognized as one of the most important working painters (1950s), he elected to withdraw his work from galleries, would show it only selectively and sell it rarely.

When the museum opened on Nov. 18, it brought to light paintings that had never been seen before. Staff began the decades-long task of restoring paintings that spent half a century rolled up and stored. And while the paintings had waited, Clyfford Still had drifted out of the consciousness of American art, leaving his contemporaries, Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko among them, to become the better known artists. They were more willing to compromise the ethic they all shared for exhibiting their work as a body and it served to raise their profile above that of the recalcitrant Still.

But while the work by Rothko and Pollock scattered to various museums and galleries, Still went on to get a museum of his own — in part because his work merits it and his last will and testament demanded it, and in part because of the devotion and commitment of those who loved him.

Perhaps one of the more significant hurdles in setting up a museum for Clyfford Still in Denver or anywhere else was convincing Patricia Still to let go of the paintings that had filled her home for half a century. Patricia met Clyfford as a student in his art class at Washington State University. He was 15 years her senior, married with a child. She would go on to follow him to San Francisco, where he and his first wife would have a second daughter. Eventually, Clyfford and Patricia moved to New York City together, where she supported him by working as a bookkeeper.

“That devotion that Aunt Pat had starting as a very young person, age 20, persisted until the day she died,” says Dr. Curt Freed, a professor and head of clinical pharmacology and toxicology at the University of Colorado School of Medicine. His mother was Patricia’s sister. “I think that attachment accounts for some of the challenges in actually getting this museum to happen.”

Patricia and Clyfford married 17 years after they met. Her commitment to Clyfford caused a family scandal that estranged Patricia from her mother for decades, and they were only ever “kind of ” reconciled, Freed says.

Clyfford stipulated in his will that his works of art, many of which had never been seen, be given to an American city that would build a separate museum to house only them.

“I found it kind of amazing that, given that independence, he would die and say, ‘I trust that the world will some day recognize the incredible value of my work and that some city somewhere in the United States will build a museum just for me,’” Freed says. “So the same guy that questioned the sort of ethics and influence of the critical art world at the time that he was painting had this incredible trust in the future.”

From his death in 1980 to the year before hers in 2005, Patricia was solicited with offers from as many as 20 cities interested in housing that museum, all of which she turned down. Freed, aware of her health, at one point was concerned that she wouldn’t make the decision before her death.

“I had the feeling that she wasn’t really that eager to have a deal,” he says. “Still was so fundamental to her life and herself, she would actually drive around in her car with his hat sitting on the seat next to her. And you know, literally, she had physical control of all the paintings and her house had Still paintings hanging on every wall, and then the majority of paintings were actually stored in one form or another in her home.”

The note she wrote to Freed in 1999 now hangs on the wall of the museum. It reads, “It just occurred to me to wonder, what would you think of having the Clyfford Still Museum in Denver?” Discussions broke down at one point during Mayor Wellington Webb’s administration, when Daniel Libeskind, the architect for the Hamilton Wing of the Denver Art Museum, arranged to visit Patricia. Clyfford had been clear. He wanted his own building, not a wing (it was for this reason that Baltimore, near his long-time home in New Windsor, Md., had been passed over).

“I accused her of not wanting to part with these paintings,” Freed says. He persuaded her to reconsider Denver when Mayor John Hickenlooper came to office. Hickenlooper visited her at her home in Maryland to discuss the option of Denver. After 20 years of discussion, and entreaties from as many cities, the matter was settled eight months later. Denver would receive the donation of 2,400 works and would build a museum — which cost $29 million — to house them. The museum would host no other artists’ works, and would not lend or sell any part of the collection.

Patricia died a year after the agreement was finalized. The asset Denver acquired is priceless. Just four paintings, which were sold with the estate’s permission to fund the museum’s endowment, earned $29 million at auction.

When the museum’s opening was announced in May, ArtInfo greeted it as a “castle for a curmudgeon,” but those who knew, or have tried to come to know Still, see him differently.

Freed was 9 years old when he met Clyfford — his first impression was of a large, black painting that dominated the living room of a New York City apartment above a typewriter store. He saw Patricia and Clyfford occasionally when they stopped by to visit Freed’s family in Ohio, driving up in Clyfford’s signature silver Jaguar.

“He was a very formal person, I would say. And yet, you know, a cordial and courteous person,” Freed says. “I thought he was, you know, decisive.

I remember, it’s funny, to be having family guests in the house and yet have his art and work come up in discussions, sort of over the dinner table, and in that environment I remember being struck by this idea that said, ‘I want to keep my work together and I am not in the business of selling paintings.’ And he remained true to that.”

“I think he was incredibly principled. There was no such thing as moral ambiguity with him,” says Dee Covington, who wrote Clyfford Still: Daring the Light, produced by the Curious Theatre Company this fall. She looked to his letters, personal items in the museum’s collection from his teaching slides to the Kraft foods jars for mayonnaise and fruit salad he used for mixing his paints, his record collection, his fedora, documentaries and video of his daughters to compile a vision of him as a character.

“One of his quotes is, ‘Clear thinking is clear painting.’ And I think he always really insisted on clarity of purpose, clarity of intention, clarity of action,” Covington says. “If you misquoted him or misunderstood his work or put something out there about him that wasn’t true, he would push back because it was his obligation to do so. … He was always pretty darn sure he was right, and I think time has revealed that he was. … Once you look at everything he was experiencing with hindsight, you realize he was right. … I don’t know if that makes him a curmudgeon or not. I just think he was holding consciousness for an entire time.”

Still wrote to Betty Parsons, who had been showing his work alongside Pollock, Rothko and Barnett Newman, in 1951, stating that he was withdrawing his work from public exhibition. “It is simply that in this particular issue of exposing my work a network of associations and evaluations entirely at variance with the implications of my act in painting are brought to bear,” he wrote. “I find these not only futile but disturbing in many ways.”

In Covington’s play, Parsons’ response to this letter is, “Good for him. Sad for us.”

His counterparts, even those who had signed the infamous “Irascibles” letter withdrawing their work from a Metropolitan Museum of Art show they felt was giving the public a “dumbed-down” version of abstract expressionism, went on to paint commissioned works.

But Still refused to compromise for the sake of a sale. “He would have someone interested in his paintings and then they would say, ‘I’d like one of your paintings,’ and he would say, ‘Well, I’ll think about it, and then I’ll also decide which one you get,’” Freed says. “So the typical thing was to offer two paintings and say ‘Do you want either one of these?’ and if the person said no, then he said, ‘Well, I guess we won’t have a deal then.’ … He would decide what the match was between an individual and the painting he was willing to sell.”

Clyfford demanded solo status for his art when it was exhibited, which drove him to take his work to a gallery in Buffalo, N.Y., that would show it alone, and led major museums, including the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, to host solo exhibits of his work in the years just before his death.

“The final show at the Met … it was the largest exhibit ever given to a living artist at the time that that happened,” Freed says. “And he knew he had colon cancer at the time of this, and so it was quite a tragic but dramatic finish to his life to have such a major exhibition.”

“He thought there was an ideal way to see his art,” says Dean Sobel, director of the Clyfford Still Museum. “I don’t think he felt this was only due to him, but he believed in it enough to forego the money. … It’s not ours to quibble with how he wanted to have his art shown.”

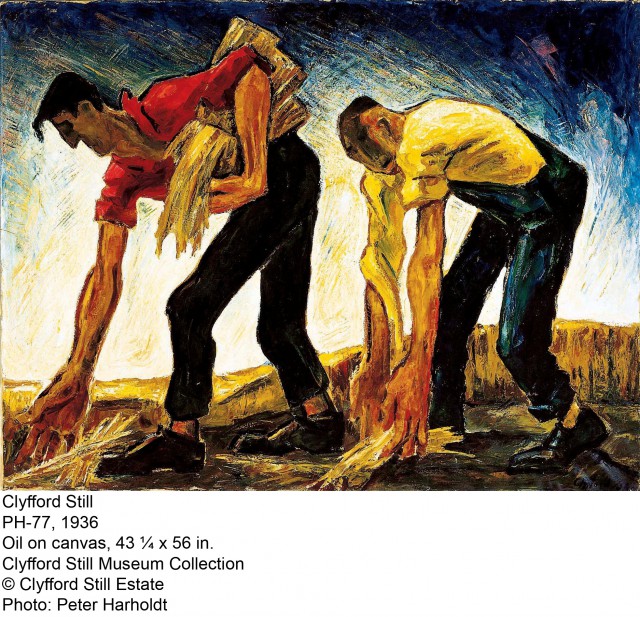

This first exhibit at the museum arranges Still’s work in the order it was made, grouped by place. As visitors move through the galleries, they track Still’s evolution from a style that bears the marks of European influence to one increasingly advanced and original. Expressionistic human forms, their faces distorted and limbs elongated, become approximated by skeletal or bone-like structures, traces of hair and a line like a profile. Eventually, those motifs vanish in favor of rising vertical forms, which later give way to torqued masses and flame-like touches of color in compositions that refuse to acknowledge the boundaries of their canvases.

“There’s a kind of continual emptying out, but never emptying out of meaning or even, kind of, subject matter,” Sobel says. “The subjects or what’s embedded in the paintings don’t change. It’s how we choose to describe them that has changed.”

Traces of European art — which took geometry as central to its abstraction, leading off from Cubism — vanished by the mid 1940s as Still began to forge his own path.

“You see this line in his abstract paintings … it’s kind of what’s left of the figure. So again these artists, I think not just Still, but these artists were very interested in having subject and some kind of meaning behind these pictures,” Sobel says.

“They’re just not pretty colors and shapes. They’re meant to be expressing kind of universal timeless themes.”

As for process, Still worked with palette knives, which created a textured surface, a torn-paper quality. Clumps of glistening paint remain.

“You have the sense of the surface of the painting and the way in which the artist lays down and shows us marks and gives us that sense that they were painted by a person at a particular moment in time is all very clear. … They’re very much alive, I think, in that way,” Sobel says. “It’s looser paint handling. They’re not tight geometries and again that expressiveness, that the quality of the line is anything but geometric. It’s almost kind of ephemeral in certain ways and it almost kind of disappears at certain times and fades into the twilight.”

Still’s work also quickly abandoned a sense of central composition. “The whole image is kind of what we’re supposed to be taking in,” Sobel says. “And the kind of boundlessness of this, the fact that things are cropped at the edges and new things are coming in, it seems as though they’re just little subsets of the larger kind of universe, like taking a picture of clouds or the sky, you know, you can only contain part of it.”

The last image in the exhibit, which dates from 1977, three years before his death and two years before his last painting, is 85 percent blank canvas.

“It’s almost as if things have just exploded apart, almost to the point like the last painting, had he lived long enough, would have been just empty,” Sobel says.

Visitors are often first struck by the richness of the color, he says.

A concrete background, textured from the rough-cut fir used to form it, and daylight through skylights bring the palette to its best.

Many of Still’s paintings arrived rolled around tubes, as they have been in some cases for 50 or 60 years. At least one of them was so large — 17 feet — that, had it arrived at the museum stretched on a frame, it wouldn’t have fit through the doors.

“Each one of them was a kind of lesson,” Sobel says. “Every painting is a moment to pause, look, understand. … Every now and then you come across a masterpiece you hadn’t even known existed.”

Museum staff unrolls the canvases and lets gravity begin the process of flattening them, later employing heat and suction to work toward getting the canvas taut around a wood frame. Storage spaces just down the hall from the restoration room tease the viewer with glimpses of the many works the museum holds but does not have room to display. — an expected 93 percent of the collection at any given time.

Museum staff will spend the next 20 years unrolling paintings and working them through the weeks of restoration necessary to prepare them for viewing.

In the galleries upstairs, the paintings are prefaced with only brief introductions. Still never titled his paintings, and they’re marked only with the date on which they were painted and a unique number.

All information to help the visitor unpack their meaning comes from a sidelined educational gallery and downstairs, where visitors can use interactive timelines and a set of custom-built cases to come to better know the man and fit his work into the historic events surrounding it from wars and the Great Depression to the emergence of pop culture icons James Dean and Elvis Presley. Among his personal effects on display are his painting jacket, palette knives, artists materials from charcoal to Crayola crayons, his books, record collection, a baseball glove and a photo of him with his daughters standing in front of his silver Jaguar.

As they have unpacked the deliveries to the museum, museum staff has found works in books and in file cabinets. The number of works on paper believed to be in the collection has risen to 1,700.

“There’s no question that he was revolutionary,” Sobel says.

“[The museum] is finally putting him into the narrative that he had written himself out of.”

The museum kicks off a series of events as a community-wide celebration on Jan. 6 with gallery talks and behind-the-scenes tours. Other events, which continue through the end of the month, include a screening of a documentary by Amie Knox called Still, presentations by and about other abstract artists and partnered exhibits at other area museums.

“I think Still and my aunt would have been thrilled to see this outcome. They could not have imagined anything better than this. Not a better building and not a better reception by a city,” Freed says. “This is a perfect outcome, and then the enthusiastic embrace by Denver has been wonderful. … Particularly for my aunt, I’m just sorry she’s not alive to appreciate this.”

Respond: [email protected]