No artist steps up to the canvas with a fully formed style. It’s easy to forget that once upon a time, famous artists were in training, finding their voice through trial and error, absorbing the world around them and translating it all through their work.

“No artist operates in a vacuum,” says Nora Abrams, curator at Museum of Contemporary Art Denver. “And no artist is alone in the studio in silence. Everyone stands on the shoulders of those before them. Everyone is always looking around at what’s happening in their own context, and some people translate that directly and some people abstract from it.”

It’s this process that is now on display in MCA Denver’s two latest shows Basquiat Before Basquiat East 12th Street, 1979-1980 and Ryan McGinley: The Kids Were Alright. Both shows , curated by Abrams, look at the cultivation of an artist. The exhibits showcase art made in the early stages of their respective careers, when both artists consistently blurred the line between art and life.

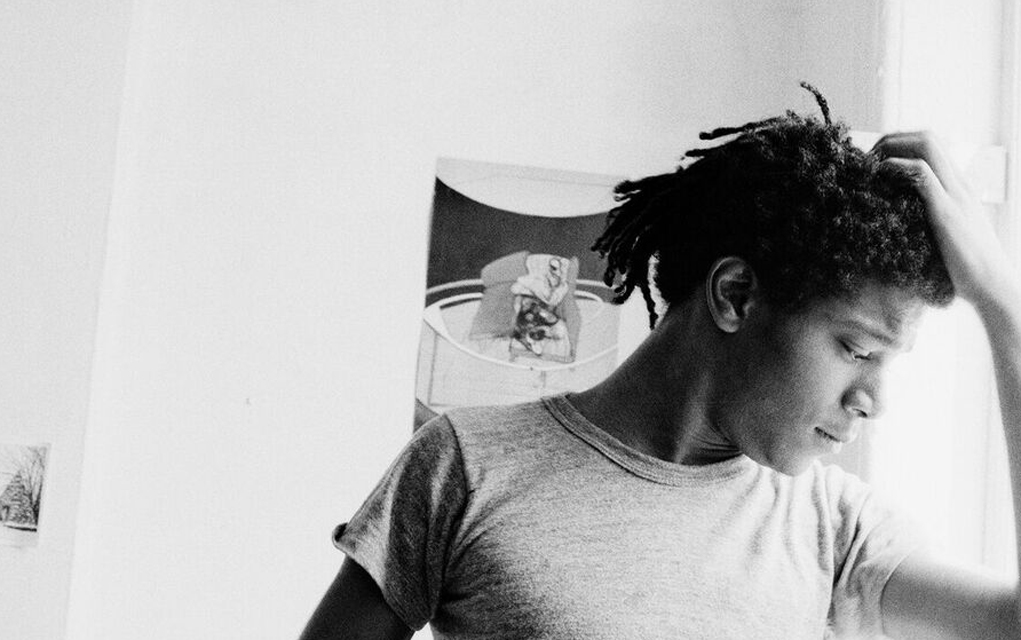

Prolific painter and neo-expressionist, Jean-Michel Basquiat is noted as one of the most influential artists of the 20th century. He started his career in his late teens, running away from home in 1978 to downtown Manhattan where he would become a well-known graffiti artist under the moniker SAMO, which aptly stands for Same Old Shit.

He bounced around from friends’ couches to living on the streets, until he settled into his first semi-permanent residence, an apartment on East 12th Street with friend Alexis Adler, who contributed the artifacts in the exhibit.

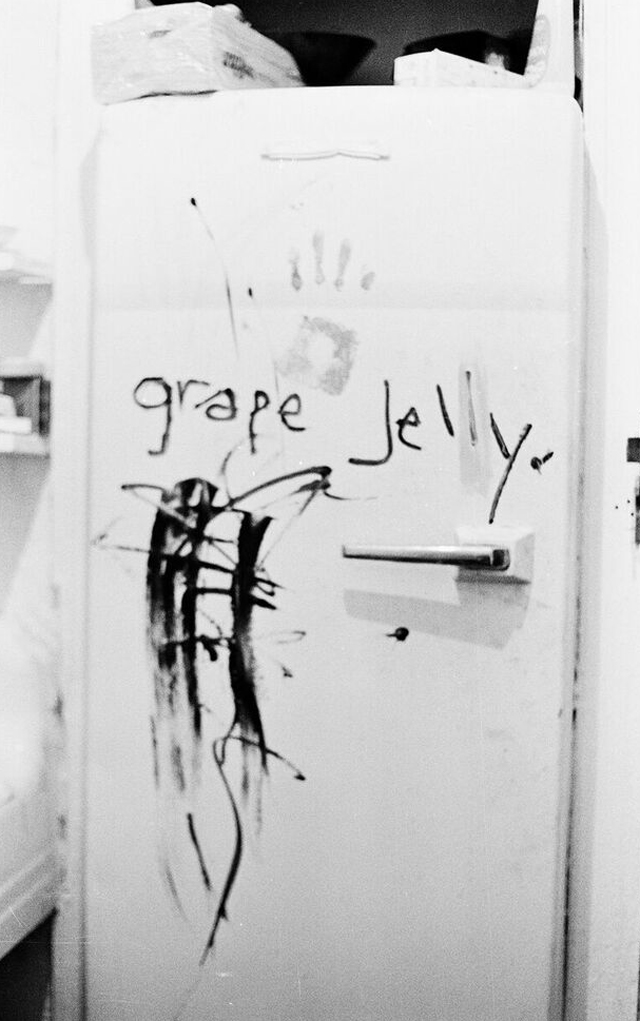

With Before Basquiat, Abrams strived to evoke the 400-square-foot apartment itself, calling attention to the details and intimacy of the objects. The space, barely enough for the two people living there, lacked a formal studio. So, Basquiat began emoting on any surface he could.

“He was this tremendously creative and sophisticated mind, filtering and absorbing ideas and refracting them in his art in all these different ways,” Abrams says. “It’s on clothing, it’s on the floor of the apartment, it’s on the refrigerator door, it’s in his notebook that he kept. It’s apparent in all these different forms.”

During this one year of his career, he dabbled in drawing, writing, music, fashion and more. In this apartment, it was the first time he was able to experiment in a sustained manner.

The viewer can see how Basquiat’s ideas evolved. He drew inspiration from anything and everything that was around him, like his roomate’s biology textbooks. In Basquiat’s notebook, on display in the show, he wrote down scientific notations and chemical symbols, which would later turn up in his mature pieces including some of his best-known works such as “Eroica.”

“It’s wonderful to be able to share … this really special insight into an artist that’s in the process of becoming,” Abrams says. “Nothing is fully formed. It’s not fully baked yet. He’s still working through a lot of different modes of making art and ideas. And therefore it’s this really rare access or window into an artist in formation.”

This notion is also apparent in The Kids Were Alright featuring the work of contemporary photographer Ryan McGinley. The show features McGinley’s work from 1998 to 2003, when he was in art school in New York, on the verge of his career. It displays his formal photography and 1,700 Polaroids that chronicle the day-to-day personal lives of McGinley and his friends, from moments of self-discovery to adventure to sorrow.

“This is a life in all of its hard living, falling in love, all the antics, all of the adventures, all the joys, all the anxieties, all the fears,” Abrams says.

In many ways, McGinley represents the next generation of artists influenced by Basquiat’s work and life. This is explicitly apparent in one of the photos taken of McGinley’s room where a Basquiat book sits on the shelf.

“There’s something of a myth of Basquiat that was so powerful to younger artists and artists coming up after him,” she says. “Right or wrong, fact or fiction, there’s a sense that Basquiat was almost too creative for this world … Ryan will admit that myth was really inspirational to artists of his generation.”

And even though their art is wildly different, the two share similar approaches.

“[For McGinley], downtown New York was both a backdrop and a muse, the way it had been for Basquiat. … [The work is] important because it exemplifies youth culture at a certain moment in time in a certain place — leaving your family, gaining and finding your own independence, before you have a lot of responsibility. What happens in those few years is incredibly impactful for anyone.”

Both artists went on to have sucessful careers, although Basquiat’s was cut short by his death in 1988, while McGinley continues to produce. Abrams says looking at the early stages of each artist’s work provides more layers of meaning by understanding the context that aided to developing their voice.

You can see the early semblage of personal style that shows up later in their work. For example, Abrams cites McGinley’s flair for working with light and capturing the body.

“Also, even when the material is gritty and difficult, it still has a youthful optimism and freedom and carefree irreverence that will continue on throughout his work,” she says.

Before Basquiat ends with one of his later works called “Untitled Cadmium” (1984), which features some of the developing patterns seen in the rest of the show fully realized, including Basquiat’s use of collage and symbols like the sacred heart.

“[The piece] is the punctuation mark of the whole project,” she says. “To basically show that all these things that you’ve seen percolating along the way as you journey through the spaces come together in his mature work.”

Both exhibits show the artists before they officially earned the “artist” title. They exemplify the young artist’s life where life and art are one in the same.

“It’s him in action of being himself,” Abrams says. “We are witnessing a life being lived.”

On the Bill:

Basquiat Before Basquiat East 12th Street, 1979-1980. Through May 14.

Ryan McGinley: The Kids Were Alright. Through Aug. 20.

Museum of Contemporary Art, 1485 Delgany St., Denver, 303-298-7554.