Gene Sherwood. Gwen Meux. Eve Drewlowe. Muriel Sibell Wolle. Virginia True. Anne Jones.

These are just some of the names of the artists who ventured into the unknown West in the late 19th century and fostered the art and infrastructures that continue to support Boulder’s artistic community today.

University of Colorado’s art department was founded by Sherwood who, alongside Meux and Drewelowe, was also a founding member of The Boulder Artist’s Guild and The Boulder Arts Commision from which grew The Dairy Arts Center and Boulder Museum of Contemporary Art.

Wolle was the head of CU’s art department for 20 years and started the museum’s permanent collection. True, a professor at CU, was a founding member of The Prospectors, a group of five artists who produced and promoted Boulder art. Jones also taught at the University and is responsible for founding the ceramics department that serves as the backbone for today’s strong community of potters.

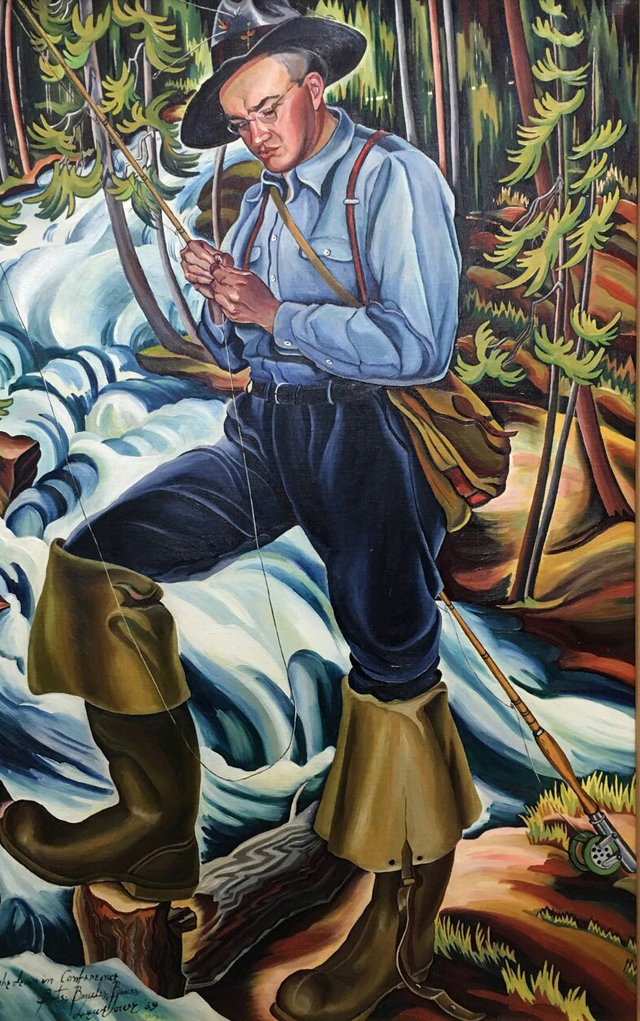

In an effort to define and understand this legacy, the works of these artists make up the ongoing exhibition at the CU Art Museum, Pioneers: women artists in Boulder, 1898-1950, curated by Kirk Ambrose, chair of CU’s department of art and art history, and Stephen V. Martonis, exhibition manager of the CU Art Museum. The exhibit is part of the county-wide arts project History of Visual Arts in Boulder (HOVAB).

In the process of curation, Ambrose and Martonis uncovered a network of personal stories that echo the formation of Western identity itself. As these artists painted and drew the landscape in which they found themselves, they also underwent a more personal exploration that is perhaps best symbolized by the names they signed their works with.

When it comes to frontiers, those who claim discoveries are typically endowed with naming rights — a gesture rife with claims to power and an assertion of ownership over what has been found or created. Many female artists of the late 19th and early 20th century were married and, as was customary of the time, assumed their husband’s names. But when it came to signing their artworks, they split with convention, scribing their maiden names or even sometimes just their first names.

“There are so many paintings where they go back and paint over the old names,” Martonis says. “Sometimes just paint over it, but sometimes put their maiden name in place.”

He says this play in signing works suggests that being an artist in the West wasn’t just about capturing the landscapes or the cultures that assimilated through settlement. It was about capturing the spirit of the West, claiming their own authority as artists, and as women.

It wasn’t until 2014 when Ambrose and Martonis were working on American West, an exhibition featuring iconic Western works from the University’s permanent collection, that they realized the importance of this specific group of women artists. They wanted to acknowledge their contributions through a separate exhibition, but moving from conception to execution wasn’t easy.

A collection of this group had never been tried before and so the curatorial duo found themselves on a frontier of their very own. The pieces were hidden in private collections, museum stocks and auction catalogs and as they searched they uncovered an art history of the West that had been overlooked for a century.

The selection of works now on display offers an unprecedented breadth and depth of Boulder’s art history.

The show covers several spectra — artistic style, historical relevance, medium and an array of subject matter. Whether it’s an abstract landscape or a charcoal drawing of a mining building, all of the art is undeniably Western. But rather than relying on typical narratives of pioneers and landscapes, it offers a more subtle exploration of their inter- and intra-personal lives as the artists sought to understand the area as much as their place within it.

Take an early landscape from Eve Drewlowe for example, scenes of Boulder foothills and the golden fields that lay at their feet, replete with her vibrant palate of color and her flair for fantastical proportions. In painting the area’s characteristic beauty, her body of work increased and matured, it became more personal, more intimate and also more abstract.

But Drewlowe’s work was not as abstract as a similarly timed series of landscapes by Sibell Wolle, who undertook an even more dramatic departure from representative techniques. Wolle’s landscapes from 1931 don’t just stand out within the context of the exhibition, but they are more generally ahead of their time. Abstraction is not common in American art until the late 1940s.

Concurrently, both of these approaches to Western landscape were housed by the same art community, testament to the flexibility and support offered for artists to press the limits of traditional paintings and sometimes to go beyond convention.

The juxtaposition of these artists’ work offers a deep look the time period and also accesses a depth within the work of each individual creator. Walking along the north wall of the museum, for example, one can see the progression from Drewelowe’s early landscapes toward her later art deco and cubic experimentations.

About halfway through that walk there is a dramatic change, as represented by the 1939 watercolor “The Reincarnation,” a self portrait of the artist lying ill in bed. She describes her revival from that illness as a reincarnation worthy of such a dramatic representation. The colors she uses are just as vivid as those in her previous paintings but suddenly, instead of blooming landscapes, she depicts fractured planes of color, abstractions of the natural world. By departing from her earlier techniques she seems to be subtly suggesting the importance of her place as someone who not only experiences the world, but shapes it, too.

As in any curated exhibition, Pioneers is just as much about what is included in the show as it is about what is omitted. The show only displays white women artists who were instrumental in forming the artistic institutions that exist in the community today. It is not about indigenous artists, slantward movements or ethnic creators. So while the show claims to be about women artists, the claim is only correct in a specific application.

Nevertheless, it is an important way in which to examine Boulder’s art history. The show is a stunning curatorial success as it unearths a never-before-seen collection of works in the process of expanding and enriching more traditionally masculine narratives of Western art. The curators, two white men, entered timely considerations of gender’s role in art as they were sometimes made keenly aware of their own biases.

Ambrose says this exhibition took many collaborations. This is the kind of excavation that corrects the narrative of the American West, which is empowering to those history forgot and enlightening to those who were unaware.

“To be disabused of my masculinist view of Western art and to the structural misogyny that continues to exist was an important aspect of the curation for me,” Ambrose says. “For me, part of the goal of scholarship, or any kind of inquiry, is to understand the different kinds of positioning therein.”

Pioneers offers an opportunity to consider Boulder’s art history through a variety of lenses and in so doing elicits important tensions about gender and art.

“There are women, even decades ago, that would have objected to the adjective of women artists,” Ambrose says. “But I think all this is to say that whatever you want to call it, consciousness raising or disabusing of preconceptions, I think all of this is to get at that moment where it frees us up. All of this is to get us to this place where we can sort of recalibrate the present.”

On the Bill: Pioneers: Women Artists in Boulder, 1898-1950. CU Art Museum, 1085 18th St., Boulder, 303-492-8300. Through Feb. 4.