A group exhibit of mixed media portraits opening at Core New Art Space on Jan. 4 is putting a face on a faceless population in Colorado — groups of refugees from Burma who have arrived in increasing numbers over the last 15 years and been met with all the struggles of strangers in a strange land.

Each year, as many as 500 refugees from Burma arrive from camps in the jungles of Thailand, unemployed, uneducated and unable to speak English. Once here, they are moved into apartments on East Colfax and given the chance to start a life in the United States. But starting a life from scratch is hard for anyone, and harder if you don’t have any understanding at all of how the systems around you work — not buses, food stamps or Medicaid. It wouldn’t take much to learn. Just a friendly face to show you around, help you understand that eggs go in the refrigerator and escalators take you all the way to the top if you just stand on that first step.

That’s the kind of work Frank Anello Jr., director of Project Worthmore, has been trying to recruit more people to do. But first, he just wants people to see that these refugees are here — some 20,000 to 30,000 refugees live in Denver. Project Worthmore focuses on the 3,000 refugees from Burma living in the city.

“We were helping everyone — we were helping Somalians, we were helping Bhutanese people, we were helping the Iraqis, Sudanese people, but what we learned was, it seemed like the people from Burma just had it the hardest,” he says of the early years of Project Worthmore, which began as Project DR, or Project Denver Refugees. “I went to the camps last year for my first time in November just to see what it was like on that side and it’s just a broken place. The people that are there, the camp life, that’s their life. They have nothing else but the camp life. They have no home.”

Most of them were farmers, but the land has been destroyed by decades of warfare and now is being encroached on by international corporations. The educational opportunities were limited to third or fourth grades. While moving around the world is challenging, Anello says, there’s no future for those refugees in Thailand.

“Ghoti” by Katie Hoffman

Giving other Denver residents a way to emotionally connect with the refugees and, hopefully, get involved with easing their transition to life in a new country has been Carmen Melton’s latest project. Melton, a portrait painter since high school, met Anello when their kids were in a class together and did a fundraiser for Project Worthmore. Curious to know more about what had gotten her daughter so excited, Melton checked out their Facebook page.

“There was this photograph of these kids that just kind of hit me,” she says. “You can tell, just by looking at them. I’m going, ‘Wow, these people have had such a hard life.’ I could just feel it immediately and it kind of struck me immediately, why don’t I just paint these people? I’ve always wanted to do something besides commissions. I just felt like commission work always kind of fell flat and it was over and done and it just didn’t have any other impact in that.”

As Melton, who moved to Denver a year and a half ago, found footing in the local artistic community and a space at Core New Art Space on Santa Fe Boulevard, she and Anello started to draw more artists into the project. The exhibition, “Our Neighbors, Ourselves,” will feature portraits from 50 artists from across the country.

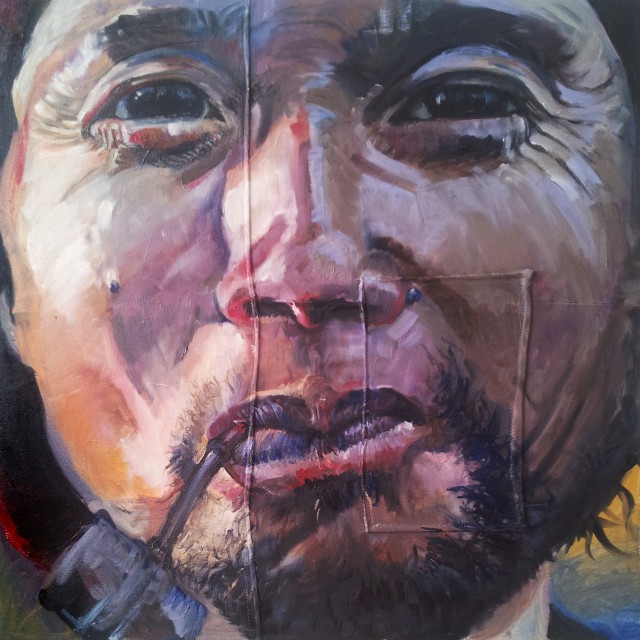

Untitled painting by Natalie Williams

“I had always wanted to make art that had more of a social impact, a more far-reaching goal other than just sitting in someone’s living room, and I’ve learned so much about the history and the people,” Melton says. “Just looking at them, I feel like I can almost feel what they’re going through, and I wanted to broadcast that to more people so they can feel that emotional connection and want to be involved.”

Anello is looking for more people to get involved with refugees the same way his work with them started — by sponsoring a single family. Four years ago, Anello and his wife, Carolyn, were recruited to sponsor a newly arrived family from Burma.

“We had no idea of anything about Burma, we didn’t know anything about refugees, especially living in our city,” Anello says of that first encounter with a family from Burma. “What sponsoring a family meant was just sort of walking along side of them, teaching them the ropes, grocery stores and so forth like that, helping their kids in school. So that’s how it all started, and through that we got introduced to a whole new world, like thousands of refugees living in Denver and Aurora that we knew nothing about.”

Over the years they’ve become increasingly invested in working with refugees, to the point that Anello quit nursing school to devote more time to Project Worthmore. Many of the 70,000 refugees who arrive in the U.S. each year don’t get much in the way of one-on-one support. They’re added to a stack of a families handled by caseworkers who often don’t have time to talk them through the day-to-day basics.

“Reflexion” by Carmen Melton

“They’re falling through the cracks in a system that’s really, really broken, so through that we decided we’ve got to figure out a way to help people,” Anello says. A former manager at Watercourse, a vegetarian restaurant in Denver, he turned there and to other restaurants, including Hooked on Colfax and Watercourse’s sister restaurant City O City, to help get the word out to the community. He is sure that there are socially minded people who want to help, but, just like him four years ago, don’t know what the problem is or what to do to help. Or even that there are people just a few miles away, living on East Colfax, which has one of the highest crime rates in Denver, in low-rent apartment buildings that are poorly maintained and often infested with cockroaches and bedbugs.

Once here, refugees have six months of benefits and six months before they’re expected to start paying back their airfare, so they’re sometimes as much as $12,000 in debt before they even arrive. That’s a lot to pay back considering that many end up with low-paying jobs such as those in a meat packing plant in Greeley. The work prevents them from having the time to attend free English classes available to them at the Emily Griffith Center — miles down Colfax from their homes on a bus system they’re not familiar with and don’t have enough passes for. And they’re working next to other people who aren’t native English speakers, so learning English is a struggle. What little they knew of the language when they arrived was likely taught in the refugee camps by another refugee or a Thai, and the three-day class they’re given on adjusting to life in America is taught by someone who’s never been to the U.S., Anello says.

“I got a phone call this week from a Burmese woman pertaining to Medicaid,” Anello says. “She said through a translator, ‘Can you come help this woman, her child is sick? She’s been sick for a week.’ I said, ‘Well, how long has she been here?’ She came in September, so a couple months, two, three months now. So I go over there, ‘Do you have Medicaid?’ ‘Yes, we have Medicaid. We don’t know how to use it. We don’t know how to make an appointment.’ So, yes, they get all these benefits, but there’s a language barrier. … It’s great that we give them these things, but what happens when the food stamp card’s not working, or what happens when their child is sick? I mean it’s difficult when you call and you’ve got to press one for English and two for Spanish, you’ve got to press one number to get to this person, and that number to get to another person, and then if you actually get to someone and you don’t speak the language, how do you make an appointment? It’s very difficult. The challenges are one after another.”

Anello has ideas for fixing that system — build a cultural center in their neighborhood to support the community-focused culture refugees bring with them from Burma, and waive airfare and extend benefits from the government for a year to allow them to learn English and develop basic street savvy for life in Denver. But for now, it’s just a start to take families in and help them through. He’s seen refugees with mentors blossom into families that can care for and support themselves, and teach us a little bit about their world and their lives.

“I want people to know who they are,” Anello says. “I want people to know that they are here to bring a whole new way of living to teach us how to live in community.”

Our Neighbors, Ourselves opens on First Friday, Jan. 4, at Core New Art Space, 900 Santa Fe Blvd., Denver. See www.projectworthmore.org.

Respond: [email protected]