During a snowy day, if you look outside the window, all you may see is a smattering of white flakes coating the landscape. But for Claude Monet, a snowy day provided delicate shades of pink, purple, blue, gray and more. The painter pushed beyond preset notions of color to find the hues beyond white. In “The House in the Snow,” cottages sit among a pile up of peach-tinted snow. In “Coming into Giverny in Winter,” a snow-covered path is rendered in streaks of cerulean and rose.

“Like many impressionists, Monet understood color,” says Angelica Daneo, chief curator at the Denver Art Museum (DAM). “Famously, their shadows were not black, they were purple. They had color in them, because a shadow isn’t really black. That sort of understanding of what colors really look like in nature, rather than what they should be like, was very important for the impressionist. Monet shows that understanding, and it’s very clear in the snow paintings … he actually saw color in them, and he was able to convey all the nuances and different tonalities you can find.”

The resulting dreamy paintings move past a photo-realistic image of a snowy day to evoke the layers within the scene. Monet exaggerates the color and light to provide a richer interpretation of the landscape, thereby infusing the image with emotion and grace.

Monet’s treatment of color is just one of the elements explored in the Denver Art Museum’s latest show Claude Monet: The Truth of Nature, now showing through Feb. 2. The exhibit features more than 120 paintings by the French impressionist and looks at the man behind the work. As the name suggests, the show uses nature to analyze Monet’s style and commitment to painting. He spent a career meticulously capturing various landscapes, and through that delivered a varied repertoire that helped spur an entire genre of art.

Monet was an integral part of the rising impressionist movement in the 18th century. Truth of Nature outlines some of the early attributes of the movement, such as leaving the studio to paint in nature, applying looser and softer brush strokes, moving away from draftsmanship and using a vibrant color palette. Monet showed at the first impressionist exhibits, Daneo says, and his painting of a bustling Parisian street “Boulevard des Capucines,” which is featured in the DAM show, was one of the paintings used to coin the term impressionism.

Paris was an integral piece of the impressionist movement, as a city in transition, modernization leading to urban renewal. The impressionist style lends itself graciously to depicting the movement of the city. In “Boulevard des Capucines,” groups of people dominate the scene. And while some details emerge — balloons, a hat, a scarf — the painting is loosely rendered, capturing the vibration of the city. This aesthetic continued in all of Monet’s work, infusing life into his scenes.

While the DAM has shown many impressionist exhibitions, Daneo says Truth of Nature is the first solo show the museum has presented just on Monet. And while many exhibitions have focused on Monet’s work in specific areas, the curators of the latest show wanted to expand the view and look at the various locations where he worked.

“More than any impressionist, he really traveled extensively,” Daneo says. “Not just along the Seine, but from London to Venice, from Norway to Belle Île off the coast of Brittany [in northeastern France]. So, this was something quite striking when you pause. The other impressionists tend to stay close to Paris or the outskirts or along the Seine. So, this search for different natures is what really struck us.”

The variety of locations showcases Monet’s range. Aside from his trademark paintings, Truth of Nature features less well-known subjects like the fog of London, palm trees off the coast of Italy and rock formations in Normandy. The artist wanted to stretch himself and find new landscapes to paint. In doing this, Monet looked to capture more than just the surface appearance.

“Through reading his letters, it’s clear he has an engagement with place and with the nature that manifests itself in that place,” Daneo says. “I found numerous times where he would use language such as, ‘I still have to grasp the spirit of this place,’ or, ‘Now I really finally found the tone of this place.’

“So, there’s this recurring motif of wanting to get to the essence of a particular locale,” she continues. “And he chose such different moods of nature, from the very bright and very sunny Mediterranean to the sinister and tragic like his works from Belle Île.”

Impressionists were recognized for their lush, colorful and bright paintings. But Monet didn’t want to be pigeonholed.

“In one of the letters, his art dealer, and I’m paraphrasing, said, ‘What are you doing there? You are a man of the sun!’ And he retorted to his wife, ‘They’re going to bore me with the sun, one must do everything.’ He really had this ability to challenge himself and to not just focus on one aspect of nature,” Daneo says.

For Monet, it wasn’t enough to just paint a tree or a cliff once. He tasked himself with studying locations. He went back at different times of day, during different seasons, striving to paint every facet of an object.

“I love this quote, when he was in Belle Île he said, ‘To really paint the sea one must look at it from the same spot every day at different times of day to understand its ways.’ He was a great observer,” Daneo says.

And even though most of his works depict landscapes, Monet was not a passive painter. He was precise and intentional with what he selected, and he would get frustrated if he wasn’t able to execute his vision. He knew what he wanted to paint and would search for compositions that he favored, such as a town reflected in water or a specific type of tree like the poplar.

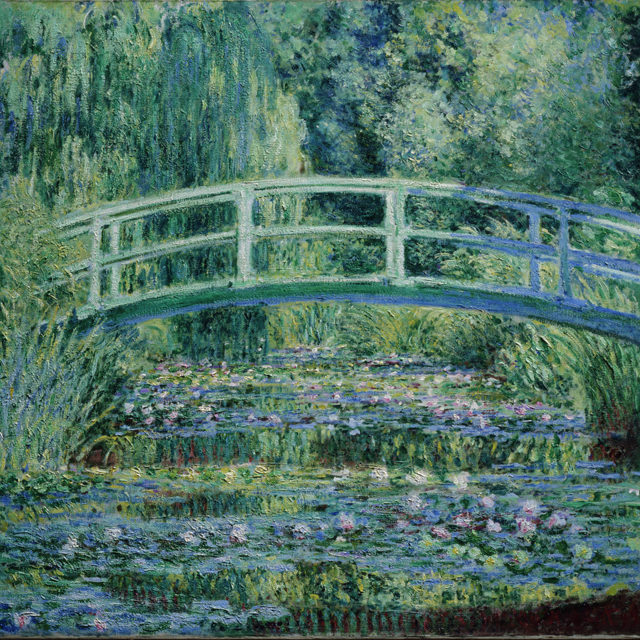

Monet’s emblematic water lilies gave the artist full control over his subject. An avid gardener, Monet planted water lilies from around the world in his pond at Giverny, where he spent the last 40 years of his life. Here he was able to fully commit to rendering the space in the way he saw it. He combined his passions and created the work he’d be most known for.

“This is an interesting symbiosis of artist and subject, which isn’t encountered often, where the artist created his own subject. He planted it, and then he painted it,” Daneo says. “There’s an intimate connection, almost an ultimate merging of artist and subject in these water lilies.”

Monet died in 1926 at the age of 86, which was a feat for that era. In his last letters, Monet spoke of plans for a new studio he was constructing — he had no plans of slowing down.

Though Monet dedicated his time to painting specific subjects repeatedly, his work never feels stale. With his passion and determination, he seemed near obsessed with translating nature onto the canvas. And as nature is constantly changing, Monet tried to keep up.

“[His paintings] don’t look tired. There’s always a genuine aspect of themselves. This was something he wanted to do, and he gave his whole self to them,” Daneo says. “Even in his series, it’s not a repetition. It’s an intentional exploration of a subject through different canvases that he showed together. But he always pushed himself forward. … I think this continuous pushing himself to seek, you can argue, for the truth of nature is something that is very inspiring and maybe a lesson that can be picked up nowadays.”

As impossible as it is to capture the many faces of nature, Monet dedicated his life to achieving the insurmountable task. And to show for his effort, he ended his career with a large repertoire of paintings celebrating nature in all its glory.

ON THE BILL: Claude Monet: The Truth of Nature. Denver Art Museum, 100 W. 14th Avenue Parkway, Denver, 720-913-0130. Through Feb. 2.