In the Spring of 2016, artist William Singer got a flat tire on his way out of Detroit. Waiting for the tow, he sat on the hood of his car thumbing through the Instagram feed on his phone and thinking about a promise he’d made to himself a few years back — by the time his 30th year came to a close, he’d land a big exhibition for his paintings. With just a few months left to realize his goal, deflated on the side of the road, Singer realized it was time to see what his dreams were made of.

Just then he saw a post from Boulder Creative Collective (BCC) — a brand new, small startup in Colorado with a mission to support artists and develop their markets. He’d heard of BCC before, from a friend of a friend, and so on a whim sent them an email to rent their last remaining studio for the summer. The next day he packed his bags, bought a train ticket to Colorado and headed west.

Unless they’re looking for a challenge, Boulder isn’t where artists typically come to test the artistic waters. For one thing, it’s expensive to live here and it’s getting more expensive all the time.

The connection between gentrification and declining art communities is a familiar tale across the country. As rent rises, artists lose their homes and studios and, along with them, the small, art-friendly businesses that host the networks crucial for artistic movements.

Boulder’s market is further hampered by comparatively low arts and culture spending, which is among the most telling indicators for the health of a local arts market. For every $33 peer cities spend on arts and culture per capita, Boulder spends just $6.

To amend the imbalance, the City of Boulder’s Office of Arts and Culture recently finalized plans to more than double current spending to $2 million by 2024. Although it’s a step in the right direction, it’s one that will take a long time to affect the livelihoods of the thousands of artists living and working in Boulder.

Without city subsidized venues, districts, fairs and grants, artists living in Boulder lack access to sales channels, public and private. In 2016, four dedicated arts spaces in the city closed their doors due to declining consumer spending.

Despite the undernourished market, the City of Boulder ranks high for the number of self-identified artists, with 9 percent of the population working in creative arts. The market might be struggling, but not for a lack of potential.

Co-founders of BCC, Addrienne Amato and Kelly Cope Russack, recognized the steep challenge facing art in Boulder and also the depth of the city’s artistic talent. Instead of waiting for the problem to self-correct, they took it upon themselves to do something about it.

“Who knows, one of our kids might grow up to want to be a poet or an artist, and I would like that to be a possibility for them, right here, in Boulder,” Cope Russack says. “We don’t live in Fort Collins, we don’t live in Denver, we don’t live in Aspen [or] New York, we live here. If I am going to raise children here, I want those artistic cultures and communities to exist here too.”

So, in April 2016, they acquired a warehouse in East Boulder and worked with local designer Barrett Rogers to build out a dozen or so studios surrounding a central exhibition space in a style that embodied the character of the project and the artistic community it sought to create.

“We knew it needed to be fluid and changeable, to grow and change along with BCC, so we built studios around the perimeter and kept the central exhibition space open,” Rogers says. “We decided to use more interesting materials than you would in a typical build, like big glass refrigerator doors and discarded pieces of wood. It’s a simple plan, but the materials add unexpected patters and details. I’m an artist and I guess that’s the way I work — I always try to use things for different situations than what they are otherwise used for.”

Just 10 months later, the studios are full — housing photographers, paper makers, painters, writers, designers — and the exhibition space, replete with moving walls, is always changing to accommodate rotating events and exhibitions. Over the summer, it was one of these studios that William Singer called home and it was there, working 10 or more hours a day, that he turned his amateur ambitions into a full-blown artistic career.

He didn’t do it alone. BCC provides professional development both one-on-one and in the form of open critiques, bolstering artists with crucial feedback to their works and processes. Within the walls of BCC, artists are not only finding themselves but one another, maturing from separated individuals into an artistic movement.

“It’s been rewarding to see that this person is connected to this person by us,” Amato says. “Not to say that we deserve some kind of recognition, but now that we are beginning to see those patterns emerge, we are taking a step back to figure out how to use that network more strategically and intentionally.”

Developing the market means hosting exhibitions and bringing buyers into the fold of the burgeoning community. To do this, Amato says the key is to bring “art into unexpected places.” They do this through programs like Art on Loan, where businesses sign on to have BCC curate art in their spaces for a year at a time, not only providing crucial exposure for artists, but also bringing art into the corporate cultures of Boulder.

More than anything, Amato and Cope Russack agree that way forward means endorsing the value of art and interweaving it into the Boulder way of life.

“I just read this article about a woman art collector,” Amato says. “She talks about her favorite piece, a Modigliani. She loves it because she sits and drinks her tea in front of it everyday. It’s not just the art, it’s that it’s a part of her daily ritual and that’s what we are trying to do with BCC — to get art in front of people, to interweave artists into our daily lives, to build a culture of art.”

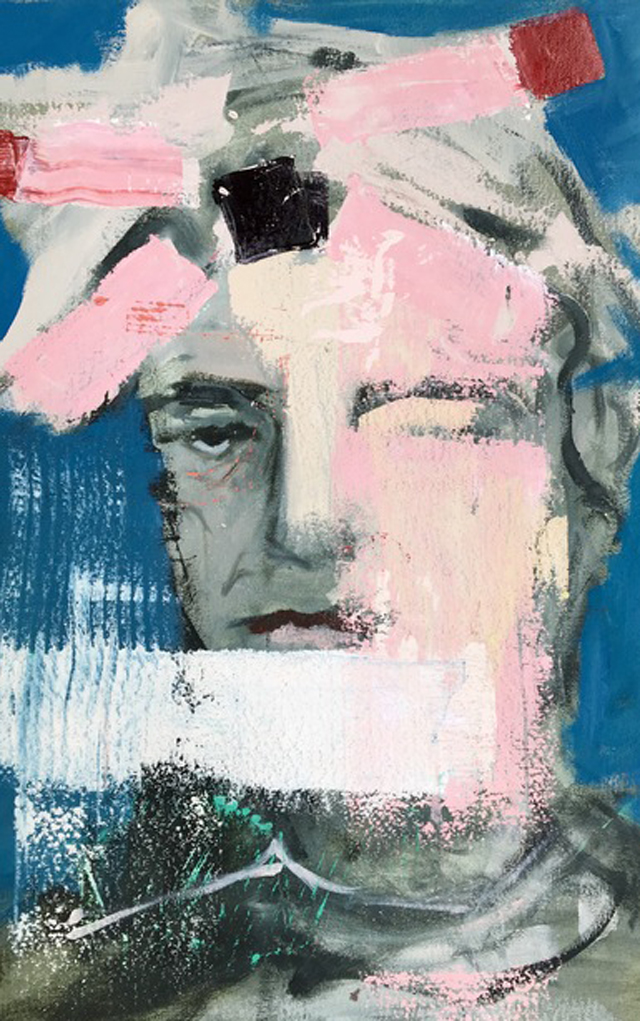

Amato has her own version of a Modigliani hanging on her wall, a painting by William Singer, the traveling painter from Detroit who came to BCC looking for his dreams and left living them. Just a week after he turned 31, he booked his first major exhibition in Savannah, Georgia. Opening later this month, the one man show is largely composed of the paintings he made right here in Boulder at BCC. “I missed my goal by a week,” he says. “But I think it’s close enough.”

Every time Amato walks past his painting in her home she falls a little more in love with the piece, more connected to her community, to her place, to her people.

“It reminds me of the reason art is so important right now, because looking at it brings me right back to the present moment. Whatever art you might bring into your home, whether it’s a mug or a 10-foot painting, it’s about connecting,” she says. “It is important that people make things. Is it relevant? I don’t know, but I do know there is immense value in what we make. It’s a connector that can bring people together, bring them into the story of their community, bring them closer to the present moment.”