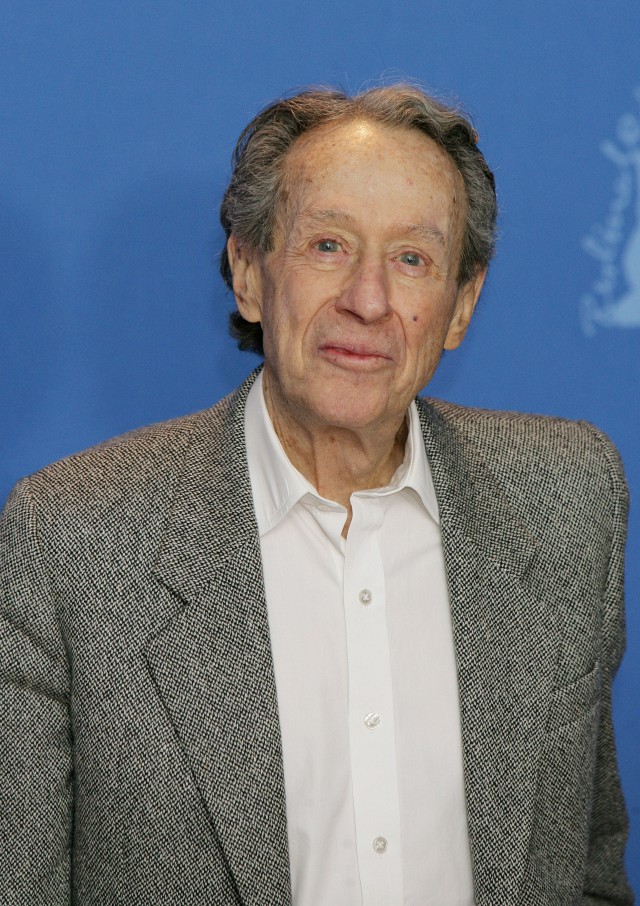

the three-time Oscar-nominated director best known for “Bonnie and

Clyde,” the landmark 1967 film that stirred critical passions over its

graphic violence and became a harbinger of a new era of American

filmmaking, died Tuesday, a day after he turned 88.

Penn died of congestive heart failure at his

home, said his daughter, Molly. A veteran of directing live television

dramas in the 1950s, Penn made his film directorial debut with “The

Left Handed Gun,”a 1958 revisionist Western starring

Penn, who was often attracted to characters who were

outsiders, directed only a dozen other feature films over the next

three decades, including “The Miracle Worker,” “The Chase,” “Mickey

One,” “Alice’s Restaurant,” “Little Big Man,” “Night Moves,” “The

Missouri Breaks” and “Four Friends.”

But during his heyday in the late 1960s and early

’70s, Penn was in the vanguard of American filmmakers and is considered

a pivotal figure in American cinema thanks to “Bonnie and Clyde,” the

standout film starring

“Had he only directed ‘Bonnie and Clyde,’ he’d be a

director of note,” film critic Leonard Maltin told the Los Angeles

Times in 2009. “But that was simply the most successful of these highly

individual, often idiosyncratic, films that he made in his heyday.”

Because of his relatively small number of films,

most of which were made before the 1980s, Penn “has a somewhat

neglected reputation at this point,” said film critic

“I think you should judge directors by their best

work,” Rainer told the Times in 2009, “and I think ‘Bonnie and Clyde’

is one of the very best American movies and is really sort of the

opening salvo for a whole generation of American directors who were

breaking boundaries and finding their own way.”

Rainer said that actors loved working with the stage-trained Penn.

“I think he’s up there with

best out of a performer,” he said. “And I think he, as opposed to a lot

of directors who have theatrical origins, had a real cinematic sense.

There’s nothing stagy about ‘Bonnie and Clyde’ or ‘Little Big Man.'”

In the late ’50s and early ’60s, Penn was best known for his work on

Among his later

Penn’s relationship with playwright

The

Penn’s 1962 film version of “The Miracle Worker”

earned him his first Oscar nomination as a director, and Bancroft and

Duke won Oscars for their performances.

“Bonnie and Clyde” earned Penn his second Oscar nomination.

The film’s famous ending, in which Bonnie and Clyde

are ambushed by lawmen and die in a seemingly endless hail of

submachine-gun fire, is considered one of the great moments in movie

history. The graphically violent ending, shot with four cameras running

at different speeds, was Penn’s primary reason for directing the film.

“I was reluctant to say ‘yes’ to doing ‘Bonnie and

Clyde’ because I wanted an ending that was simply not just violent,”

Penn said in an interview for Turner Classic Movies. “I wanted one that

would, in a certain sense, transport — lift it — into legend.

“And it wasn’t until I woke up one morning and I

could see that scene with multiple camera speeds and the shape of the

almost ballet of dying, and then I knew that that was a film I wanted

to make — desperately.” The release of “Bonnie and Clyde” ignited a

critical firestorm.

Outraged by the film’s “blending of farce with brutal killings,” veteran

hideous depredations of that sleazy, moronic pair as though they were

as full of fun and frolic as the jazz-age cutups in ‘Thoroughly Modern

Millie.'”

But New Yorker film critic

American movie since ‘The Manchurian Candidate.’ The audience is alive

to it.” Newsweek critic

But then he watched the film again and famously

reversed his position in a second review the next week, saying that he

considered the first review “grossly unfair and regrettably inaccurate.”

The Chicago Sun-Times’ young film critic,

had no such second thoughts, declaring in his review: “‘Bonnie and

Clyde’ is a milestone in the history of American movies, a work of

truth and brilliance. …Years from now it is quite possible that

‘Bonnie and Clyde’ will be seen as the definitive film of the 1960s.”

The movie’s core audience, Penn told the San

Francisco Chronicle in 1996, were the same people who were questioning

the Vietnam War and viewed the film’s notorious bank robbers as an

extension of their own rebellion.

“They were acting that movie out months before we

had made it,” he said. “They were in a kind of collective revolt and

the self-recognition that leaped off the screen is really what swept it

along. … It resonated in a way that I never expected.”

As for the violence in the film, he told the Dallas Morning News in 1999 that he “considered ‘Bonnie and Clyde’ to be about

“I was attacked for the violence in the film,” he

said, “but I wanted to show shootings as they really are — bloody and

horrifying — so the

Nominated for 10 Academy Awards, including best picture, “Bonnie and Clyde” won Oscars for

Beatty, who also starred in Penn’s 1965 film “Mickey One,” praised Penn in a 2000 interview with

“His intelligence,” Beatty said, “is the factor that

resonates most strongly, his intelligence and a lack of interest in

pandering.”

Film editor

“I would cut the phone book for Arthur,” she said.

Penn was born in

Penn’s parents — his father was a watchmaker, his mother was a nurse — divorced when he was 3, and he and his brother moved to

Penn later said he moved so often while growing up

that he attended at least a dozen schools over an eight-year period. At

14, he and his brother moved back to

While in high school in

acted in school plays and worked for a local radio station, voicing the

words of world leaders in dramatizations of events in the news. He was,

he later said, “a terrible actor.”

Penn received his first chance to direct at a local

amateur playhouse. The idea of becoming a director, he told the Boston

Globe in 2008, “just emerged. I was drawn to the theater as kind of a

lonely kid. … I went there, really, for company.”

After joining the Army during World War II, he used his weekend passes while training at Ft. Jackson in

Penn served in the infantry in

He began as the stage manager for a production of the play “Golden

Boy.” But after being demobilized, Penn succeeded Logan as head of the

company whose casts consisted of professionals and amateurs.

A year later, Penn returned home from

at the University of Perugia and the University of Florence. Penn

launched his career in television in 1951 as a floor manager for

But when his old friend Coe called him in 1953 with an offer to direct, Penn returned to

Directing assignments on other live dramatic anthology series, such as “

Penn, a former president of the

The couple later divided their time between homes in

———

(c) 2010, Los Angeles Times.

Visit the Los Angeles Times on the Internet at http://www.latimes.com/.

Distributed by McClatchy-Tribune Information Services.