The legacy of Orson Welles looms large in the history of cinema. So large, even Welles himself fell into its blackness.

“The word genius was whispered into my ear — the first thing I heard — while I was still mewling in my crib,” Welles told biographer Barbara Leaming. “It never occurred to me that I wasn’t until middle age!”

Genius? Possibly. Artist of impeccable persistence? Positively. And lucky for you, the University of Colorado Boulder’s International Film Series will screen four films from cinema’s wunderkind to prove it: Citizen Kane (April 22), The Lady from Shanghai (April 23), Touch of Evil (April 24) and The Other Side of the Wind (April 25); all unspooling on 35mm and all introduced by Boulder Weekly film critic, me, Michael Casey.

Born May 6, 1915, in Kenosha, Wisconsin, Welles was a man of multitudes and quick to fame. His picture first appeared in The Capital Times in 1926 with the caption: “Cartoonist, actor, poet and only 10.” A decade later, he strode onto the stage of the Auditorium Theater in Chicago during a blizzard that had shut the city down.

“Good evening, ladies and gentlemen,” Welles told the sparsely populated crowd. “My name is Orson Welles. I am an actor. I am a writer. I am a producer. I am a director. I am a magician. I appear on stage and on the radio. Why are there so many of me and so few of you?”

Welles was not a humble man, but he was a hard worker. Success on the stage brought him acclaim, but success on the radio brought him attention. Welles quickly moved from famous to infamous, particularly on Halloween 1938 when his broadcast of H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds caused a panic, convincing many listeners that Martians were invading New Jersey.

Where does one go after they create a national panic? Hollywood, naturally. Though the studios had beckoned Welles to the dream factory before, he refused to go until RKO Pictures promised the 23-year-old a contract that allowed him total control, from start to finish, over a movie of his choosing.

It was an unheard-of contract for the time, and Welles wisely snapped it up and set about adapting Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness for the screen, envisioning the movie as an entirely subjective film. Similar to how the first-person novel worked, the camera’s eye would stand in for Marlow’s “I” of the narration, with Welles providing the voice while also playing Marlow’s obsession: Kurtz.

But Darkness was not to be. However, it did give Welles an idea for how to frame his next story. Working with writer Herman J. Mankiewicz, the two used a similarly shadowy character, this time a reporter, to tell the rise and fall of a newspaper tycoon, business tyrant and failed politician. They were going to call the movie American, but they settled on Citizen Kane.

Based on stories Mankiewicz collected from his time at parties hosted by newspaper mogul William Randolph Hearst, Kane explores the objects, romances and aspirations a hollow man collects in his quest for more. Hearst, smelling slander, tried to have the movie destroyed. He could not, but he did the next best thing: He used his newspaper empire to bury the movie and destroy Welles’ career. Never again would Welles find the financing and control that he had been afforded for Kane.

But Kane was more than enough for Welles to catch the movie bug. And despite myriad frustrations he encountered over the next three decades, Welles turned out phenomenal work after phenomenal work, each one a hallmark of experimentation despite being hamstrung by tight budgets or lack of overall control.

Take The Lady from Shanghai, with Welles playing opposite his wife, Rita Hayworth. It’s far from perfect, but perfection be damned. Shanghai is an enthralling piece of work culminating in a funhouse hall of mirrors scene full of shadowy violence and self-hatred. It would inspire Bruce Lee to make visual his philosophy in Enter the Dragon, and no doubt had some level of inspiration for Jordan Peele’s latest film, Us.

Shanghai is Welles through and through, but considering the movie was produced at the height of the film noir movement, Welles allows the genre’s hallmarks of corruption, deception and bleakness to bleed all over this sailor’s tale. But even Shanghai can’t hold a candle to 1958’s Touch of Evil, a story of absolute power and absolute corruption along the U.S. southern border.

Here, Welles plays police captain Quinlan, a man whose looming authority is beyond question. But Quinlan’s reign may be coming to an end. When the captain demands tarot card reader Tanya (Marlene Dietrich) predict his future, she doesn’t even pick up the cards.

“Your future’s all used up,” she says flatly.

You can almost hear Jacob Marley rattling those ghostly chains.

Touch of Evil should have been Welles’ return to form, but Universal Pictures found the movie confounding and, despite Welles’ pleas, re-edited and re-structured the film, butchering it in the process. Thanks to editor Walter Murch, Touch of Evil was restored to Welles’ vision in 1998, but back in ’58, the damage was done. Financing and distribution were hard to come by, projects were started and abandoned, and critics began to assert that Welles had a fear of completion.

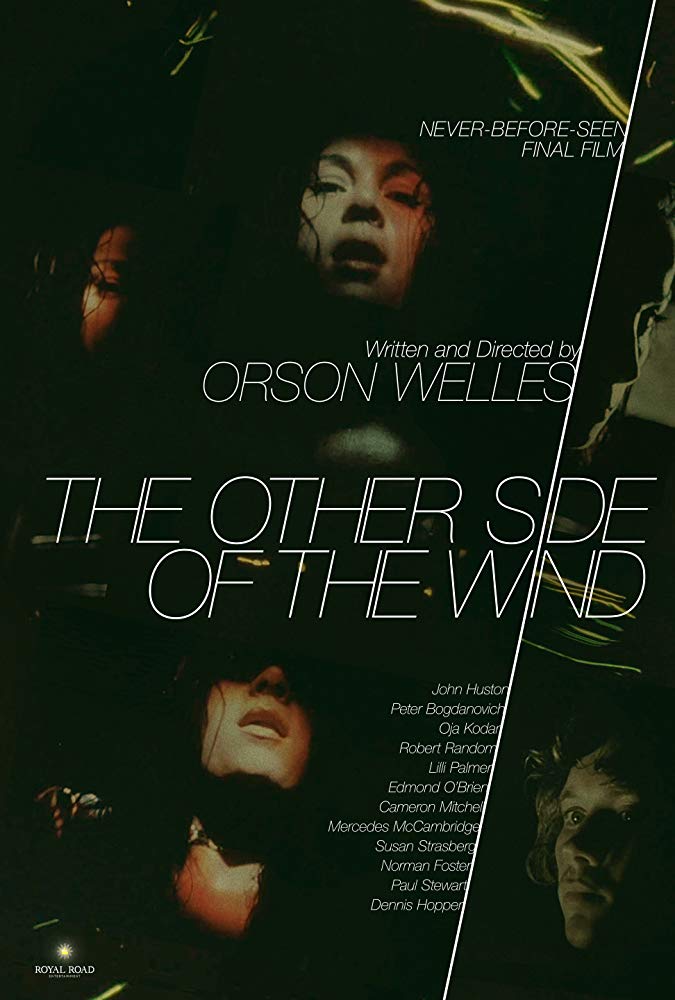

It all came to a head in 1970 when Welles began work on The Other Side of the Wind, a movie about making a movie, about the accompanying backroom dealings, about the hangers-on one attracts and about the backstabbing that inevitably follows.

Wind was to be Welles’ comeback; a statement that no matter how tastes changed, would always resonate. Alas, it was not to be, and Welles would never finish Wind. On Oct. 10, 1985, the filmmaker suffered a heart attack and died in a Los Angeles hotel room while working at his typewriter. He was 70.

But thanks to the movies, Welles will never be gone. Because of the tireless efforts of producer Frank Marshall, cameraman Gary Graver and friends Peter Bogdanovich and Joseph McBride, The Other Side of the Wind was completed and released in 2018. More works are still to be found and restored, and they will be. There are few figures in the history of cinema as big as Welles, and there is still much to be discovered in each of his films, not to mention the number of ripples still radiating out from them.

“The one key element we learned from Welles was the power of ambition,” Martin Scorsese has said of the filmmaker. “In a sense, he is responsible for inspiring more people to be film directors than anyone else in the history of cinema.”

ON THE BILL: ‘Citizen Kane’.” Monday, April 22, 7:30 p.m.

‘The Lady from Shanghai.’Tuesday, April 23, 7:30 p.m.

‘Touch of Evil.’Wednesday, April 24, 7:30 p.m.

‘The Other Side of the Wind.’Thursday, April 25, 7:30 p.m.

International Film Series, Muenzinger Auditorium, 1905 Colorado Ave., Boulder.