“Hold on just one moment,” Gerda Rovetch says over the phone, “I just need to fortify myself with a pen.”

She wants to take down my name and note the time we’ve set to meet the following week to talk about a retrospective of her work that’s currently on display at Bricolage Gallery at Art Parts Creative Reuse Center in Boulder. A quiet moment passes; and then another; and another before the 95-year-old artist reassures me all is well.

“Don’t worry — I’ve got my faithful walker to help me.”

It’s clear what Art Parts executive director Denise Perreault meant when she wrote to me that Rovetch has an “incorrigibly playful mind.”

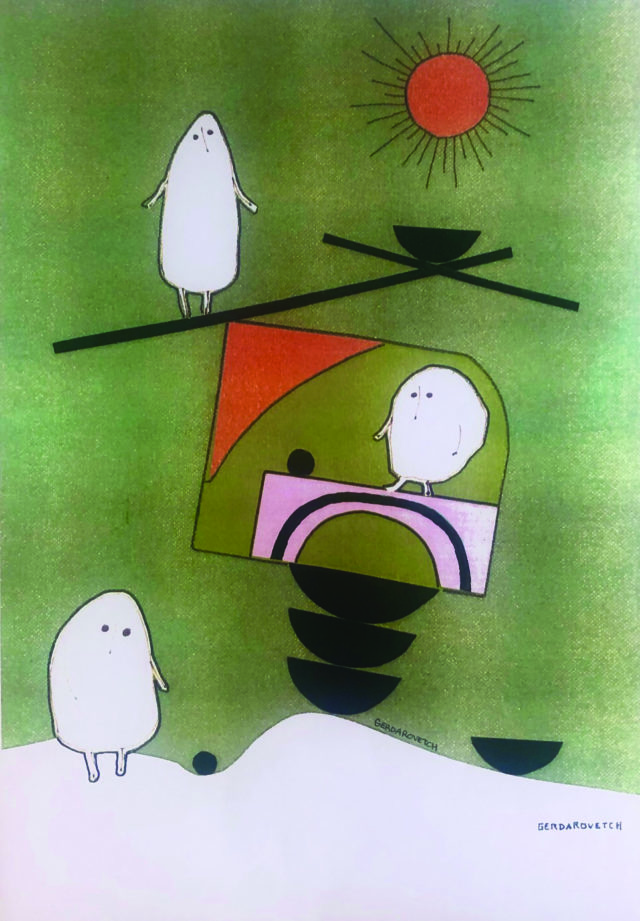

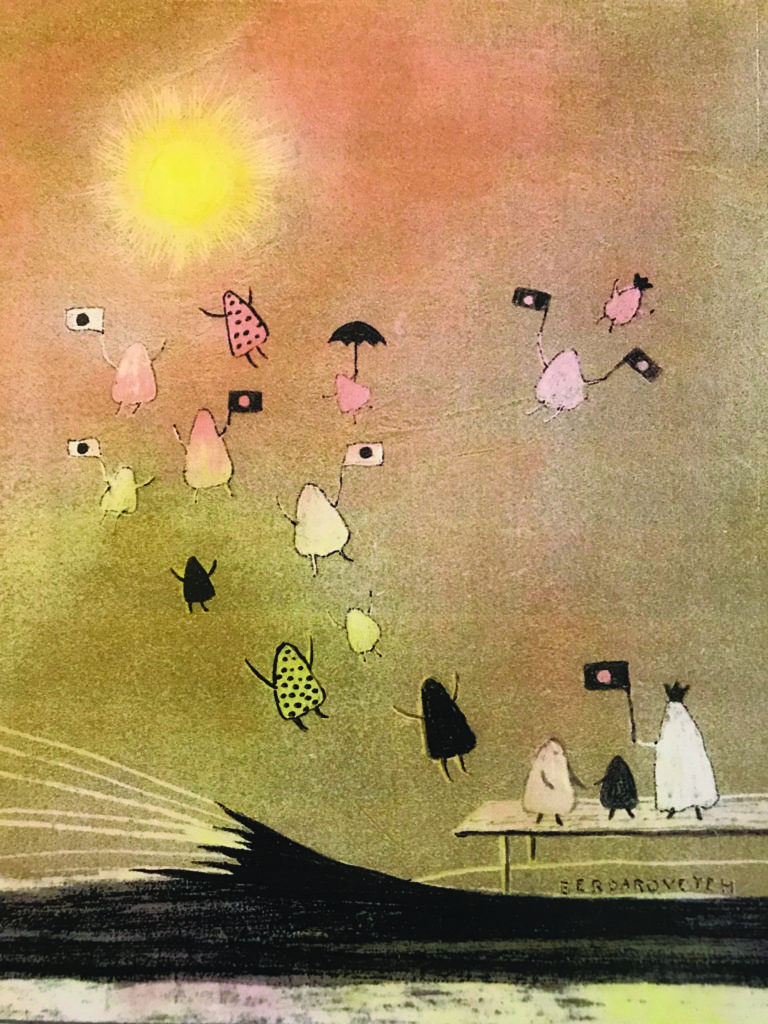

“I’ve been following her ever since seeing her in numerous Open Studios [events] since the early ’90s,” Perreault says of Rovetch. “That’s where I really fell in love with her collages, and especially the ones that she calls ‘potato people.’”

The retrospective, called Potato People and Other Flights of Fancy, offers a taste of Rovetch’s penchant for the unconventional, of her love of whimsy and poetry and life’s simple pleasures.

“There is just this lovely playfulness and yet something deeper going on there, too,” Perreault says. “A balance and a symmetry and a sophisticated asymmetry. There’s an intellectual quality to it that I just found captivating.”

Rovetch’s art delivers poignant messages about the absurdity of life — from balancing the many facets of our lives to laughing in the face of loss — in deceptively playful code… for those interested in scratching the surface.

The retrospective comes right on time, as the nonagenarian has just self-published her second book of playful poetry and drawings, Uncles.

Long live Gerda Rovetch.

• • • •

A few days after the phone call, Rovetch — faithful walker at her service — invites me into the streamline moderne home on Highland Avenue she shared with her husband, Warren, for decades, up until his death just two years ago. The couple moved to Boulder in the late ’50s and have called it home ever since. Warren was an artist in his own right, creating a series of travel books over the years when he wasn’t busy penning significant research papers on economics or pedagogy; his memoir, according to Wikipedia, “looks back over 70 years, from managing a high school nightclub to the 1946 World Student Congress in Prague, then on to Belgrade and a confrontation with Tito, escape out of a train window in Ljubljana, turning down the general’s mistress in Trieste, living with El Greco in Rome and other adventures in Paris and London, ending with a degree from Oxford and happy marriage.”

“I’ve got an idea,” Rovetch tells me as we head to the kitchen for drinks. “Do you like pie?”

There are photos of Warren and Gerda, their three children and several grandchildren on a counter in the kitchen, spanning black-and-white to color, across 58 years of marriage and beyond. Walker at her side, Rovetch pushes a button on an electric kettle to heat water for tea, then stretches upward to pull two mugs down from a cabinet.

“This is my favorite,” she says of a cracked mug decorated with blooming roses. “The fact that it’s cracked makes it all the better, as you never know when it might break.”

Her daughter Lissa, in for a visit from her home in San Francisco, joins us just as we’re about to sit down with ample slices of cherry pie at a wrought-iron patio table overlooking the backyard. Flower pots surround us near and far, and Rovetch has fortified, if you will, almost each and every one with silk flowers. These bring color all year long, she tells me, which makes her happy.

“One of my mottos is: If it works, don’t knock it,” she tells me between bites of pie.

• • • •

Rovetch forged her laid-back attitude in the face of global upheaval as an adolescent growing up in WWII-era Europe. Her family left her hometown of Leipzig, Germany, in 1938, when Rovetch was just 14.

“It was just a few weeks before [the Nazis] would start the kristallnacht, the ‘crystal night’ in Germany,” she says. “My father had planned that we would leave. He had talked to somebody who said [Hitler’s regime] seem to be hugely enlarging some camps of some kind and he wanted us out of the country.”

Rovetch’s mother packed two suitcases for the family and ushered them aboard a train for Switzerland one evening soon thereafter. Gerda Rovetch wouldn’t return to Germany until 1981.

A couple years later the family settled in London, where Rovetch’s father had business, right as The Blitz began.

The young Gerda and her sister spent much of their time in bomb shelters at school.

“I’ll tell you what I learned from the war,” Rovetch says. “The sirens will always go on again, and there will always be an all-clear, and the silence will always go on again, and that’s life.”

In London she discovered a bit of herself in the off-beat humor and childlike art of James Thurber’s cartoons. Thurber would go on to be known for his work with The New Yorker. His art was an affirmation to Rovetch, a sign that it was OK to be silly — something that was often hard to do during war-torn years in Europe… and something that could be hard to do as a German.

Rovetch tells me a joke to make her point:

“A German man is walking across a bridge and a drowning Englishman shouts from the river below: ‘Help me, I can’t swim!’ And the German goes to the edge of the bridge and shouts down, ‘I can’t swim either, but I don’t make such a fuss about it.’”

She studied academic art for a while at college before being called to help in the war effort. As an 18-year-old woman, she worked as a draftsman, drawing up schematics for a machine that could make underwater repairs to ships.

“I was just totally alone at this huge drafting table,” she says. “Some days I didn’t see anybody at all. It was a horrible, horrible, horrible time, but it was OK. I survived it. I lived with my family, because since I was only a refugee, they didn’t have to pay me for much.”

Some stories never change, it would seem.

After the war Rovetch returned to school, studying pottery at Camberwell Art School before opening Isis Pottery gallery. She soon met Warren Rovetch, a Denverite at Oxford studying economics on a Fullbright Scholarship. These were good days, Rovetch tells me, full of friends and laughter. Soon, Warren would ask Gerda to marry him and move to the States.

“He said, ‘If you marry me, you can have all the children you want. … We’ll have a sailboat with red sails and you can have a room of your own. And I knew what that meant,” Rovetch says. “It meant you can do your own stuff.”

And that sounded pretty good to Gerda.

• • • •

The newlywed couple lived in New York for a few years, where Rovetch spent much of her time at the Arts Student League, creating mixed media collages under the creative eyes of painter Richard Pousette-Dart and collagist Leo Manso. Through these artists she learned to be “bold as a burglar” and to always trust her instincts.

After the couple settled in Boulder in 1957 and got their three young children into school, Rovetch got involved in art classes at the YWCA, serving on the board of directors and the programming committee for years.

“They were not really classes,” Rovetch says. “They were like the Art Students League, you know; we would get some good artists from Denver to come and we would all do whatever we wanted.

“The thing that drove me crazy was … I have so many facets [to my art] that sort of wanted to come up all at once and I couldn’t figure out what on earth did I want to work on,” she says. “It was uncomfortable for me … and then I started to compartmentalize and essentially three different things surfaced.”

With no pottery wheel at her convenient disposal, Rovetch began to work on Japanese-style watercolors that honored her love of the land, oil pastels that paid homage to her love of color, and collages that tapped into her childlike wonder of the world.

Over the years she helped establish the Mustard Seed Gallery, a cooperative of artists that functioned on Pearl Street for nearly a quarter of a century. Her art rarely stayed on the walls long.

“I would argue she is perhaps the best-selling collage artist in Colorado during her lifetime,” says Art Parts’ Perreault. “It’s almost a certainty that if you show art with Gerda in a gallery she’s going to outsell you.

“I do feel like she’s a secret,” Perreault says. “Is it because she’s female and female artists rarely get the accolades they deserve? Is it because she’s humble?”

Humility is Rovetch’s secret weapon. It disarms you when you realize how lucid she is, how independent, how active and social.

Ask Gerda and she’ll tell you it’s the child inside.

“It keeps the wonder alive,” she says as she finishes her slice of cherry pie. “Often I feel abandoned because my husband died, or distraught about the state of the world and of the country and whatever, but very little things delight me, little things I discover. I’m very grateful. I love the unexpected, a little of the absurd.”

Gerda Rovetch’s work can be purchased at R Gallery in Boulder, 2027 Broadway, rgallery.art

ON THE BILL: ‘Potato People and Other Flights of Fancy: A Gerda Rovetch Retrospective.’ Bricolage Gallery at Art Parts Creative Reuse Center, 2870 Bluff St., Boulder. Through Oct. 5.