Sushi was far from hip in the mid-1960s when an 8-year-old named Gil Asakawa arrived in the U.S. from Japan with his family. Actually, few Americans had even heard of it. When they did, the initial reaction to sushi was less than enthusiastic.

“When we moved to the States, sushi was gross. Eat raw fish? Uh-uh,” Asakawa says with a laugh.

Now, sushi rolls are available at almost every supermarket, kids take them for school lunch with that familiar green wasabi glob and pickled ginger, and sushi bars (including some with conveyor belts) abound. Ramen, too, has evolved from being an obscure Japanese noodle to a staple grocery item in American pantries, and ramen shops now popping up in shopping centers.

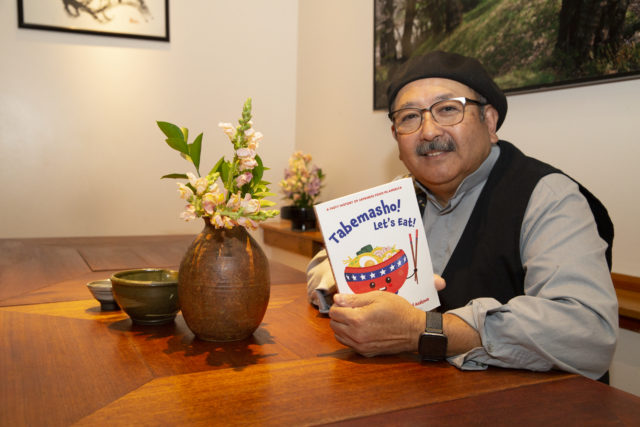

Asakawa traces the path those foods — as well as tempura, Hi Chews and mochi — have taken in becoming mainstream in his engaging book, Tabemasho! Let’s Eat!: A Tasty History of Japanese Food in America, freshly published by Stone Bridge Books.

More than a chronicle of the evolution of Japanese home-cooked, packaged and restaurant foods in America, Tabemasho! is an engaging first-person page-turner by the Tokyo-born author.

“I didn’t want to write an academic research paper. It’s personal. It’s my journey through Japanese food,” Asakawa says.

Asakawa is a Colorado journalist, music critic and author of the book Being Japanese American. An avid home cook and gardener, he writes about his foodie life in his blog, NikkeiView.com.

His dining habits have always embraced both cultures with traditional American and Japanese dishes on the table. “When I was a kid, we could be eating spaghetti and meat sauce, but there was always rice on the table,” he says. Occasionally, the cultures would collide.

“I’d bring friends home after school and my mom would be cooking dinner and it would be something terrible-smelling like fish head soup. I’d have to say, ‘Sorry guys, my mom’s cooking,’ and we’d run upstairs to my room,” Asakawa says with a laugh.

He also discusses the touchy subject of culinary assimilation, the process where a dish like sushi or spaghetti gets Americanized and loses its original identity. It happened in Japan, too. “I love Japanese curry. It’s a thicker, milder gravy with potatoes and beef served over rice. I thought it was Japanese food when I was growing up, but it’s really borrowed from the British, who stole it from India. Tempura came from the Portuguese,” Asakawa says.

Asakawa’s family moved to Colorado in 1972 and Tabemasho! explores the evolution of local Japanese restaurants, including such influential Denver eateries as Tokio, Kokoro and Sushi Den.

Asakawa also spent time dining in Boulder at places like Pearl Street’s Kobe An, the city’s first major Japanese eatery. Surprisingly, Kobe An was not the eatery that introduced Boulder to the joy of raw fish.

“The first place in Boulder that had good sushi was Pelican Pete’s (now the location for Backcountry Pizza and Tap House) in the early 1980s. It was a fish restaurant that shipped in fresh seafood,” Asakawa says. “They had a tiny sushi counter and hired a bunch of Japanese sushi chefs. My dad would take us all to Pelican Pete’s and spend two hours eating and yacking it up.”

The restaurant that probably did the most to popularize sushi in Boulder was Sushi Zanmai, which opened in 1986 under the direction of saxophone-playing owner Masao Maki. “Zanmai was big because it was rock ‘n’ roll,” Asakawa says. “Maki brought a different American element to sushi bars. The Emperor and Empress of Japan even ate some of his food when they visited Colorado.”

He notes that Amu, Zanmai’s sister eatery next door, was the first traditional izakaya to open in Colorado. An izakaya is a Japanese tavern that serves small plates.

The process of culinary assimilation is a long path.

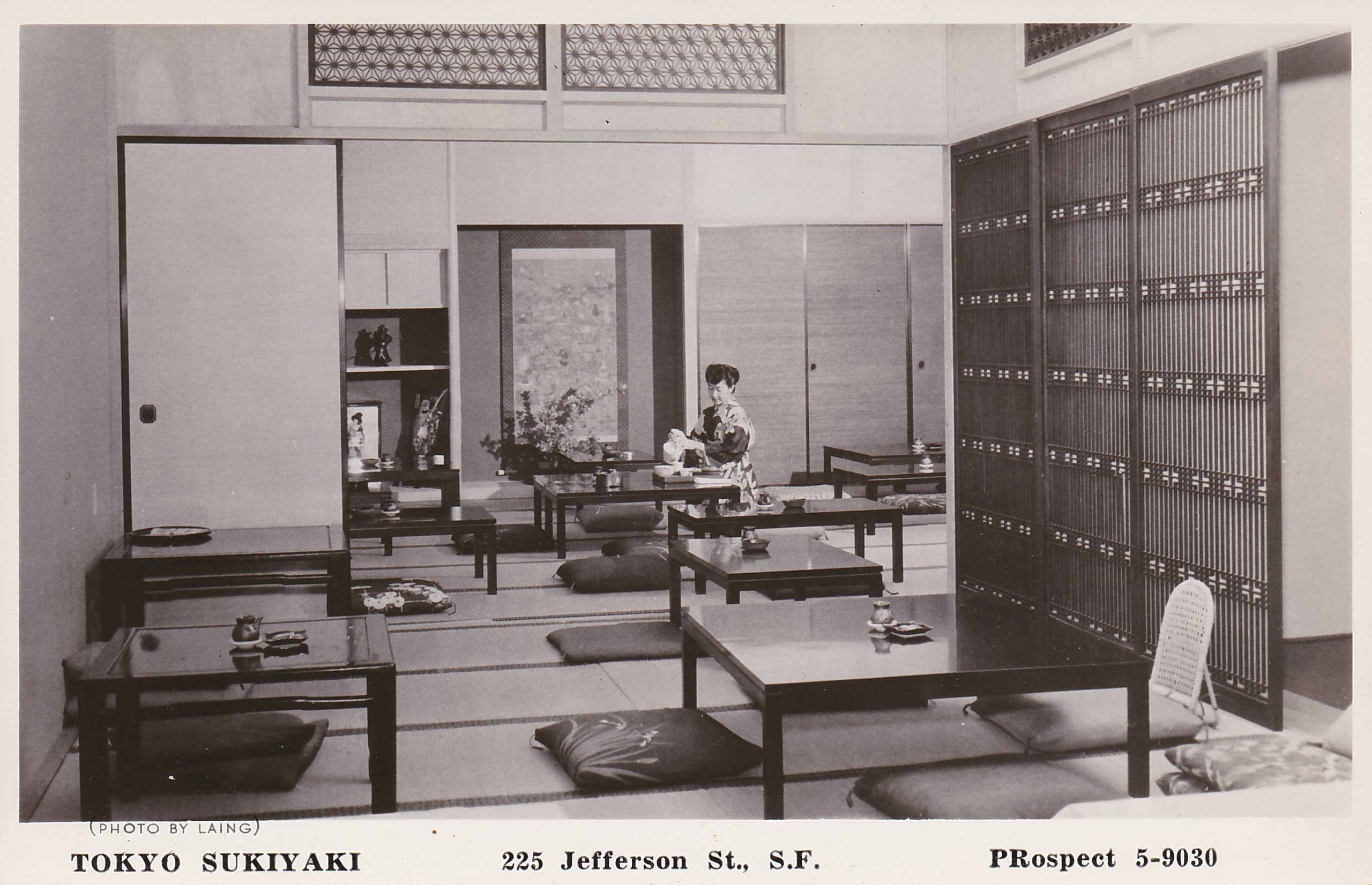

“For almost 100 years there were only three kinds of Japanese food that most Americans knew: sukiyaki, teriyaki and tempura. Today when you say ‘Japanese food’ most Americans have a similar tunnel vision. They think sushi and ramen,” Asakawa says.

Sometimes when a dish migrates it can get lost in translation. “In Japan, even the best ramen is rarely over $10 a bowl. You can easily pay $17 or more at one of the fancy ramen places here,” Asakawa says. “It’s great that ramen has caught on in such a way that hipsters will wait an hour for ramen that isn’t necessarily that good.”

The book also explores the origins of American variations on a Japanese theme that can be viewed either as innovations or abominations. Take the hugely popular California roll. “It was made by Japanese sushi chefs for Americans,” Asakawa says.

Other chapters focus on Japanese beverages and candies like Hi-Chews — mango is my favorite — and Kit-Kat bars, a particular Japanese obsession. It’s all written in Asakawa’s witty, accessible voice.

Asakawa devotes a section of Tabemasho! to Japanese foods he believes Americans will never learn to like because of texture or aroma.

“There are a lot of popular foods in Japan that are slimy. Mountain yams are just all slime,” he says.

Natto — a popular Japanese fermented soy food — is distinctly sticky, stringy and smelly. In the book, Asakawa reveals that some JAs — Japanese Americans — call it “snotto.”

Some delicacies such as basahi (horse meat) and kujira (whale meat) will never be popular because of cultural and moral objections.

In Tabemasho!, Asakawa details a long list of the next Japanese foods rapidly gaining popularity, from Wagyu beef and nori seaweed, to matcha green tea, miso soup and mochi.

“My hope is that people who like sushi and like ramen will read the book and get curious about tasting other things, like okonomiyaki,” Asakawa says.

Okonomiyaki are savory Japanese meat, vegetable or fish pancakes now featured on many Japanese eatery menus. They are a specialty at Osaka’s Restaurant in Boulder.

John Lehndorff hosts Radio Nibbles Thursday mornings on KGNU (88.5 FM, streaming at kgnu.org). Email: [email protected]