The National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) is much more than a place for the most prestigious climate scientists in the world to work; exhibits and learning opportunities afford anyone who enters the center the option to experience something about the environment in a way they might not have before.

Currently on display, Weathering Climate matches scientists and artists in collaborative projects to highlight a particular environmental issue with the hope of reaching a wider audience, as art communicates primarily through storytelling and visuals, and science communicates through mathematics and charts. The union of science and art in this exhibit draws visitors into the broader concept of climate change and how we all must interact with it.

“Arts and sciences have different ways of seeing the world,” says Marda Kirn, executive director of EcoArts Connections, who helped organize the exhibit. “The more ways we can pull together these different ways of seeing the world to try to understand climate change and what we can do to work towards solutions, the better off we’ll be.”

Working with curator Lisa Gardener of the UCAR Center for Science Education, Kirn coupled artists and scientists together from all across the country including some locals. For instance, scientist Peggy Lemone and artists George Peters and Melanie Walker became a team. The triad joined forces to create a sculpture to interact with the wind and highlight the dangers of continued fossil fuel use.

Peters and Walker came up with a sculpture design, for their piece “Warm Memorial,” a large walkway now situated in front of NCAR’s main entrance. The piece includes a series of chords connected to poles anchored in the ground. Hanging from the poles are black rocks representing coal. The intent is to show the relationship between the wind and power consumption, and ultimately the climate system. When the air blows through the sculpture, the chords move and vibrate, creating sounds that give voice to the wind while highlighting its erratic movement across the landscape.

“I’m not sure how George and Melanie settled on what they did, but they managed to capture both the wind and climate change in their sculpture, which looks to me like a series of ‘doorways,’ which captured the sound of the wind going from doorway to doorway to doorway,” says Lemone. “It gives you a visceral appreciation for the movement of that wind gust that is captured quantitatively by that grid of wind sensors.”

With the black rocks weighing down the sculpture, the chords are made to look like wires on an electrical grid. And the piece makes a statement about the heavy reliance the United States places on fossil fuels to generate energy.

“Making artful statements on current issues often keeps them in the public mind and view. The more discussion of these important milestones keeps all of us engaged in our environment. We tend to gravitate toward works that light up or inspire a wordless sense of awe,” Walker says. “It is our curiosity and wonder of our environment and surroundings that should inspire us to save them.”

Glimmering in the sun, and making the invisible wind visible, the sculpture’s message points toward using renewable energy in the future.

The trend is, however slowly, beginning to change. In 2010, the United States used coal to generate close to 2 million gigawatt hours (GWh) of energy, and in 2015 that number dropped to about 1.2 million GWh, according to the Environmental Protection Agency. Wind energy is on the upward trend, albeit not rapidly. In 2010, the U.S. generated 15,000 GWh worth of energy from wind power, and in 2015 that number rose to almost 200,000 GWh.

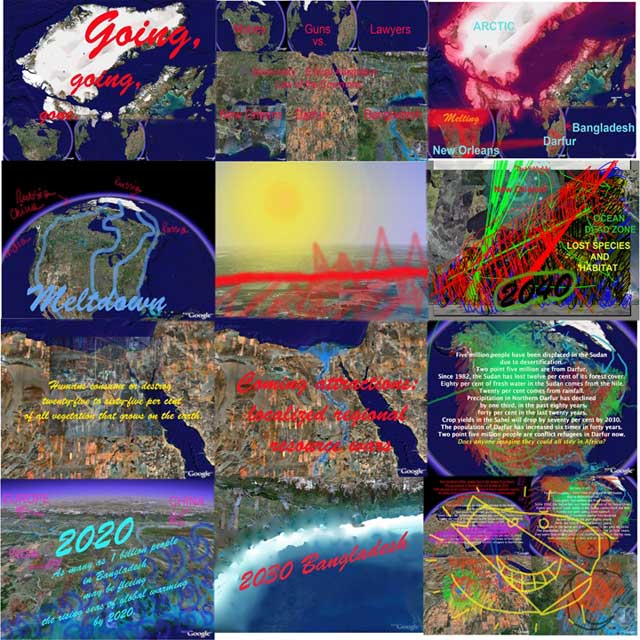

Another piece in Weathering Climate questions what changes should be prioritized to combat a threat that is no longer existential. In “Trigger Points Tipping Points” Dr. Jim White, a paleoecologist at the Institute for Arctic and Alpine Research (INSTAAR) worked with Aviva Rahmani, an affiliate at INSTAAR, to look at the possible effects of climate change on water systems, like an increase in global sea levels or the exhaustion of freshwater sources. Using predictive models and data visualization by drawing over Google Earth, White and Rahmani pulled together different types of data about population concentration and resource depletion to highlight problem areas around the globe and expose where climate change might affect the world most.

“Our conversations were about what elements needed to be prioritized based on scale and drama of impact,” Rahmani says. “For example, when drought leads to geopolitical disruption in Egypt or the Sudan, due to competitive conflicts over water loss, or [how] sea level rise in Bangladesh or the Gulf of Mexico would lead to a likely trajectory of massive human migrations to other parts of the globe.”

“Aviva would draw and put into visual art the ideas that we were kicking back and forth,” White adds.

For example, one visualization shows the erased coast of Bangledesh, as the rising sea level is expected to swallow up miles of coastline. The stills also highlight the threat of mass immigration if sea level rise causes displacement from coastal cities around the Gulf of Mexico.

Using data from both satellite measurements and trends based on tide gauges, the EPA has determined the global average sea level has risen about 9 inches since industrialization in the 1880s. White says people are the major agent of change, no longer riding as passengers on planet Earth, but taking the driver’s seat instead.

“If we were just talking about issues that only dealt with the physical environment, and human beings didn’t have much of an impact on that, then fine. But indeed, we find ourselves today being the major agents of change around the planet,” White says. “And not just from an energy or climate point of view, but in terms of nitrogen in the water, and everything.”

It is necessary to get information about environmental issues out and NCAR is free and open to the public, hoping to reach as widespread of an audience as possible.

“There is a frustration among scientists that we have not been able to effectively communicate what we see, particularly in terms of climate change,” White says.

And collaborating with artists has eased that frustration, enabling the science of climate change to reach a broader audience through creative interpretation.

“Human survival and the survival of the planet as we know and depend upon it,” Rahmani says.

“These are changes that have just huge implications that right now people aren’t digesting,” White adds. “And really the only thing that stands between several meters of sea level rise and today’s level of [carbon dioxide] is time.”

As all the work in Weathering Climate demonstrates, the clock is ticking on Earth’s climate system.

Interviews with Peggy Lemone, Melanie Walker and Aviva Rahmani were conducted via email.

On the Bill: Weathering Climate. NCAR, 1850 Table Mesa Drive, Boulder, 303-497-1000. Through Jan. 6, 2017.