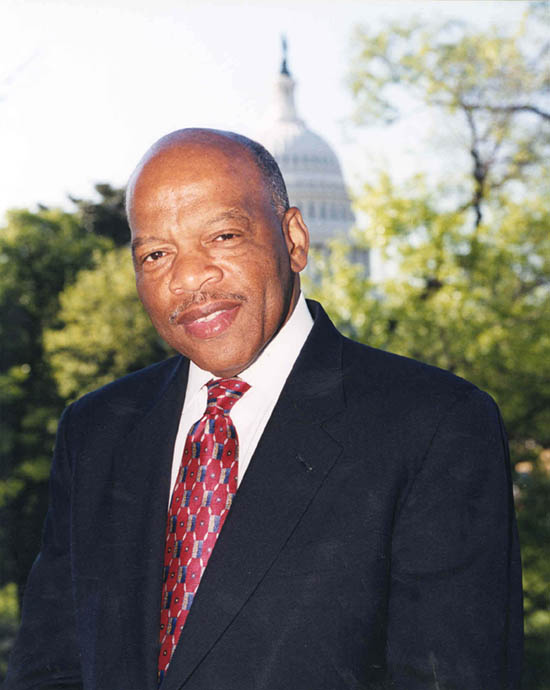

Boulder Weekly spoke with Rep. John Lewis (D-Ga.) about the Civil Rights Movement, the Freedom Rides, and parallels between the struggle for racial equality and the struggle to eliminate discrimination based on sexual orientation. Lewis will speak about the new documentary Freedom Riders at the Boulder International Film Festival on Sunday.

Boulder Weekly: You knew you’d face verbal threats and maybe some physical violence, but were you surprised they literally blew up the bus on your first stop?

John Lewis: I was on the original group, part of the original 13 that left Washington D.C. on May 4, and we were prepared, we had been trained, we knew there was a possibility of violence, and the possibility that we would be beaten, arrested and jailed, but we didn’t have any idea that it would be so severe, that people would try to burn people, blow up people on a bus, burn a church with people in the church, but the freedom rides, in my estimation, before this film, was one of the untold stories of the civil rights movement. It was a movement with so much drama.

I grew up in rural Alabama, 50 miles from Montgomery, and so growing up there, you visit a bus station, you saw the signs that said white waiting, colored waiting, white men, colored men, white women, colored women — segregation was the order of the day. I traveled for four years by bus to college, leaving rural Alabama, going to Montgomery, from Montgomery [Ala.] to Birmingham [Ala.], Birmingham to Nashville [Tenn.] to school and back every year. Black people and white people couldn’t be seated together in the same waiting room at a lunch counter, at a restaurant, couldn’t use the restroom facility, couldn’t sit together on a bus, and we were out to change that.

BW: During the freedom rides, I was surprised to find out that help on the national level didn’t come as soon as it should have. Did your views of John F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr. change during the freedom rides? One refused to come in and stepped in when it became a big story, and one pretty much refused to help when things were starting to get violent.

JL: We wanted greater assistance and involvement from the department of justice, from the attorney general and from the president. This became the very first major test for the Kennedy administration relating to civil rights and the American South. I guess President Kennedy and his advisors didn’t want to do anything to hurt their standing in the South. We had sent a letter, a telegram I believe, telling him that the freedom rides were going to take place, and apparently, someone put it an inbox, and they didn’t notice it or anything until the violence occurred in Alabama. But there had already been some violence in a little town called Rock Hill, South Carolina, where my seatmate, a young white gentleman, the two of us started in a so-called white waiting room, and a group of young white men attacked us and beat us and left us lying in a pool of blood. And the ride continued through South Carolina, through Georgia without any problems in Georgia, and people met with Dr. King in Atlanta, and between Atlanta and Birmingham, those traveling on the Greyhound bus were attacked at Anniston, Ala., where they attempted to burn people on the bus. When we got to Anniston, I was not on the bus, I had gotten off, it’s a long story and I don’t want to bore you with it.

BW: Go ahead.

JL: I had applied to go abroad to Africa, to India, so after the violence in Rock Hill, S.C., I had to fly to Philadelphia for my physical, then I was supposed to rejoin the ride in Montgomery. But I never made it to Montgomery. Those traveling on the Trailways bus were beaten in Birmingham at the Trailways bus station there, so I went back to Nashville and met with people in the local movement, and we decided to pick up where the original group that I was part of had left off.

So on Wednesday, May 17, 1961, 10 of us, seven men and three young women, one young white man, a young white woman, left Nashville, and when we got outside of Birmingham, there was one young black guy and one young white guy sitting together on the front seat, and the police commissioner Bull Conner met the bus and told them to move. They refused to move and they were arrested and taken to jail. And then Bull Conner had the bus driver take the bus into Birmingham and asked to see our tickets. And our tickets read from Nashville to Birmingham, Birmingham to Montgomery, Montgomery to Jackson, and Jackson to New Orleans. He let the regular passengers off the bus and ordered us to stay on the bus, and he had them place newspaper and cardboard over the windshields and the windows so the press could not see what was happening on the inside. And then he decided, an hour and a half later, to take us into protective custody — that’s what he told us — and place us in jail. We stayed in jail what, Wednesday night, all day Thursday, Thursday night. Early Friday morning, he came up to our cells and said he was going to take us back to Nashville, and he took us to the Alabama-Tennessee state line. He left us, this is nothing but Klan territory, and a car came to pick us up, and we went back to Birmingham and tried to board a bus on Friday afternoon, on Friday, May 19, and the bus driver said I have only one life to give, and I’m not going to give it to [inaudible] or the NAACP and refused to drive. And throughout that night, each time they would call a bus from Montgomery, we would try to board the bus, and the bus driver would refuse to drive over and over again. Bobby Kennedy at one point said to the official at Greyhound, “Do you have any colored bus drivers?” He thought white drivers were refusing to drive the bus, and Greyhound didn’t have any [colored drivers]. And one time he became so frustrated he said, “Let me speak to Mr. Greyhound!” [Laughs]

Finally, they worked out an arrangement Saturday morning, that would have been May 20, 1961, with 11 other students that came from Nashville and Atlanta, we boarded a bus that would leave at 8:30 in the morning and arrive in Montgomery about 10 or 10:30, and they would have a private plane flying over the bus, and every 15 miles there would be a patrol car. Along the way, almost all the people on the bus went to sleep, and I was sitting alongside the young guy that had been arrested earlier and had been released from jail, the charges had been dropped against him, a young white student, so the two of us started off the bus, the others coming behind us, and the moment we got down off the steps, an angry mob came out of nowhere, 100s of people, with bricks and balls, chains.

BW: So where are you, you’re still in Alabama?

JL: Yes, in Alabama, at the Montgomery bus station. And they started beating not us; they turned on the press. So if you had a pencil and a pad or had a camera, you were in real trouble. A lot of the young men was able to jump over a fence and go into a basement of a post office, and most of the young women got in a cab. They got in a cab owned by a black cab company, and the black cab driver said he couldn’t drive a cab, because the law in Alabama was that blacks and white could not ride in the same taxi cab. So the young white woman got out and started walking down the street, and a guy by the name of John Seigenthaler, he was a representative of President Kennedy and Robert Kennedy, asked them to get in a car, that he was a federal agent and he would get them away from the mob. And they said no. And he said, “But I’m a federal man, I need to get you all out of there. And they hesitated and while they were hesitating, a member of the mob went up and hit John Seigenthaler, this representative of President Kennedy, in the head with a pipe and left him unconscious in the street. And then they turned on my colleagues and started beating us and beat us so severely, we were left bloodied and unconscious in the streets of Montgomery.

That was on that Saturday morning, and two of my colleagues were hospitalized, including my seat mate, and we planned a mass meeting for the next day at [a church] where Dr. King was going to come speak, and before the meeting even started, there were more than 2,500 people trying to get into the church, and an angry mob marched on the church and started burning cars, throwing paint bombs into the church, and Dr. King went down into the basement of the church, called president Kennedy, called Robert Kennedy, and told them what was happening, and President Kennedy called the U.S. Marshall and federalized the Alabama National Guard. If it hadn’t been for President Kennedy and Bobby Kennedy, I think a lot of people probably would have died that night or been seriously hurt in that church.

The general of the National Guard came into the church and said it was a very bad situation outside, it was dangerous for anyone to leave, and ordered everybody to stay in the church. And early that Monday morning, he had jeeps to transport all of the freedom riders to a home of a successful African American business man, a guy who also had been an airmen during World War II, a Tuskegee airman, but we stayed, including Dr. King and [the church’s reverend], for two or three days until we made the decision to continue the ride. There’s a famous photograph of Dr. King with his arm out of the window, because we had asked him to go on with us on to Jackson, Miss., but since he was on probation for something in Georgia, he decided it was probably best for him not to go. So the Alabama National Guard, the following Wednesday morning, escorted a group of us to the Montgomery Bus Station to board a bus to go to Jackson, and around 11, another group got on the bus, and they took us all the way from the Alabama state line to the Mississippi state line, and when we got to Jackson, Mississippi, the Mississippi National Guard led us to the bus station, and that’s when we were arrested in Jackson. More than 300 people were arrested and went to jail.

BW: Is that how many people were on the freedom rides at that point?

JL: Right. During that period of time, people kept coming over a period of time. … Maybe in one group there would be five or six, maybe 10 or 12 … primarily students, but a lot of religious leaders came from all over the country.

BW: Have you spoken with any of these politicians that were helping institutionalize racism and helping enforce these Jim Crow laws? Have you spoken with Gov. Patterson?

JL: No, but I did speak with [former Alabama] Gov. [George] Wallace once, and I asked him why did he give orders to the troopers to beat us on a bridge on bloody Sunday, and he said to me, well John, he didn’t hate black people, he said in effect that the struggle was not a struggle between the civil rights movement and him, or the state of Alabama; it was with the federal government, but he said there were people waiting on the other side of the bridge to kill us. And I said, governor, well do you almost kill people to keep other people from killing them? And he didn’t have an answer.

BW: Do you believe him when he said that?

JL: No.

BW: How do feel about guys like Wallace and Patterson and even others like Strom Thurman, when they say they’ve renounced their racist ways?

JL: I think mainly guys like John Patterson, the governor of Alabama at the time, said they couldn’t be babysitters for these people, or “nursemaids,” something like that, for these people who were coming into the state to stir up trouble. But people had a right to travel in interracial fashion to test the decision of the supreme court, and the officials of Birmingham, the police officials, they knew that there was a mob waiting in Montgomery to beat us.

There was one decent man, who was head of the Alabama State Troopers, his name was Floyd Mann. Several years later, after I had been in Congress, I went back to Montgomery for the dedication of the Civil Rights Memorial near Dr. King’s old church, and Floyd Mann was there, and he came up to me and said, “Congressman Lewis do you remember me?” And I said, “Yes, Mr. Mann, how can I forget you?”

He was there. He was the one that had told John Patterson, if he gave him the authority to protect the freedom riders, he could do it. But Patterson never gave him. So on that day when we were being beaten, and the mob was doing all they were supposed to do, Floyd Mann fired a gun straight into the air and said, “There will be no killing here today. There will be no killing here today. And the mob dispersed.”

Mann since then has passed. But I tell you, one of the guys that beat me and my seatmate in Rock Hill, S.C., two years ago. It was February ’ 09, he came to Washington and said he wanted to meet with John Lewis, and came to the office and said, “Congressman, I was one of the people who attacked you on May 9, 1961, at the Greyhound bus station in Rock Hill. I apologize, and will you forgive me?” And I said yes. He hugged me, and he started crying. I hugged him and cried. I’ve seen him a few times since then.

BW: Do you accept his apology?

JL: Oh yes, buy all means. That’s what the movement was all about, to build a sense of family and move towards reconciliation. We were not out to hurt anyone; we were not out to destroy anyone. We were out to be reconciled.

BW: How important was it to the freedom rides that it was both white and black people participating?

JL: It was very important to have both black and white participants in the movement. Because white people, if you had black friends or traveled together, you couldn’t be seated together in the same seat or section of the bus. You couldn’t be seated together in the waiting room; you couldn’t use the same restroom. And we had to end it. And there were hundreds of thousands of whites who felt the same way as black people, that we had an obligation to do what we can to end segregation in public places. After we had been arrested in Jackson … we saw segregation again. Whites and blacks couldn’t stay in the same jail cell. We were arrested together, but all of the white men were taken to the same cell place, the same bullpen, black people were take to another, with both black and white men with both black and white women, and when we got to Fielder City Jail to the county jail in Jackson, one day they decided to take us to the state penitentiary called Parchman, and Parchman was a very bad place — people wrote about it in porns, and [inaudible] and stories — it was not a great place. People always coming up this and that, saying if anything ever happens to you, try not to go to Parchman. But we all went to Parchman. That morning they drove us down in mid-summer, 1961, they took us down to Parchman, and we get out of our big van that had taken us. The jailer came out with his rifle drawn, and I don’t know what he said to the women, but he said to the black and white men, he said, “Sing your goddamn freedom songs now. We have niggers here. They will beat you up. They will eat you up.”

Then they led all of us into a long hallway in the maximum security unit of the prison and ordered us to take off all of our clothing, so we all stood in a long line without any clothing, just naked, the guns still drawn on us — we didn’t have any weapons. We believed in non-violence! We weren’t gonna attack anyone. Then they ordered us in twos to take a shower, they gave us razors, and if you had a mustache a beard, any facial hair, you had to shave it off. Then in twos, they placed us in a jail cell for two. These bunk beds, nothing on the bottom mattress that the prisoners had made … we were still naked, and I guess 45 minutes, an hour later, they brought us a pair of shorts, sort of these army fatigue green shorts and undershirt, that we kept on, we all were sentenced to 66 days and a $250 fine. We all wanted to get out within 44 days in order to appeal our cases, and most of us stayed in for 40 days.

BW: 40 days?

JL: Yeah, including the time in county jail and Parchman.

BW: What was going on while you were in prison?

JL: There were present all over the country, lawyers trying to get us out. On one occasion, we came out, went off on bail, and they called us all back. Eventually all of the cases were dropped or dismissed. I think the film is telling the story of what happened and how it happened. But by Nov. 1, 1961, the Interstate Commerce Commission issued an order banning discrimination in public transportation all across the south. And those signs — white men, colored men, white women, colored women — those signs came tumbling down.

It also carried the civil rights movement from the large towns, the cities, and from the college campuses, to the larger community, into the rural south, the small towns and the small communities. During voter registration … people would refer to the voter registration volunteers as the freedom riders. “The freedom riders are coming, the freedom riders are coming.”

BW: What would you tell your children if they were the ones embarking to do it?

JL: I would have encouraged them to do it. I would have encouraged them to stand up. You have to stand up for something. As Dr. King said, if you fail to stand up for something, you will fall for anything. Somebody had to stand up, someone had to go on the freedom rides, someone had to take the beatings, someone had to take the risk.

BW: Would you do it again?

JL: Oh yeah, I would. I think some of us grew up and came of age on those buses, in those waiting rooms. The same way that we grew up sitting down on lunch counter stools. We had to grow up. We became committed. I remember the original group, 13 of us, seven whites and six African Americans. We didn’t know whether we would return, but we had to do it. Right now I’m looking on my desk, I have photograph from Montgomery, and it’s a waiting room, white intrastate passengers. And this soldier form the U.S. Army, he’s standing in the door of the waiting room, keeping people from coming in to harm the freedom riders.

BW: Is there an equivalent of the freedom riders today?

JL: No, no I don’t think so. It was dangerous. It was very, very dangerous. People wanted to see change. People committed to the philosophy of nonviolence. I think what we see in Cairo, what is happening in the streets there in the center of the city, is the spirit of the philosophy and the discipline of nonviolence at work.

BW: What do you see as the next civil rights battle in America?

JL: I think the next real effort must be for all of us to come together, to work together as citizens, as a family, as the American family, to build a greater sense of community, to help people that have been left out or left behind. It doesn’t matter if you’re black, white, Latino, Asian American or Native American. A lot of people talk about a post-racial society with the election of President Obama. People ask me all the time is it a fulfillment of Dr. King’s dream, and I say no, it’s just a major down payment. We still have lots of work to do.

BW: How far has civil rights come since the 60s, and how far do we have to go?

JL: Oh, we’ve come so far. We’ve come such a great distance. We’ve made so much progress. When I hear people say nothing has changed, I feel like saying, “Come and walk in my shoes. I will show you change.” It was a different world, a different America. But we still have people who can’t get health care, cannot get enough to eat. People without shelter; there are too many homeless people in this country. People cannot find work, so we have to create jobs, and a sense of security, so our children can get the best possible education

BW: What are your thoughts about living in a post-racial society, and what do you think of that term?

JL: It doesn’t exist. We’re not there. The scars and stains of racism are still deeply embedded in American society. It’s important for us to educate and sensitize all our young people, they should watch the story of the freedom riders, watch Eyes On The Prize, read the literature of the civil rights movement.

BW: How do you see race relations today?

JL: It is much better. As I said before, people are not going to be discriminated against in places of public accommodation. It is rare to see someone denied service at a restaurant, in a lunch counter, in a hotel. … Young people growing up today, when they see those signs, colored white, it’s in a book, in a museum, in a video. So they must be taught what those signs meant for another generation.

BW: Do you see any parallels between the civil rights movement and the battle for equal rights for gay and lesbian people?

JL: Oh yes, discrimination is discrimination. That’s why I have taken such a strong stance. How can you be quiet when you fought to end discrimination based on race and color? You have to stand up and speak out and speak up and be involved in a struggle against discrimination based on sexual orientation.

BW: Going to the gay rights movement, do you support gay marriage?

JL: As Dr. King said during another period during the ’50s and ’60s, when people would ask him should blacks and whites get married, he said, “Races do not fall in love and get married. Individuals fall in love and get married.” If two men or two women want to fall in love and get married, then it’s their business. No state or no government should tell a person who they should fall in love with or get married to.

BW: Do you foresee years in the future, say gay marriage gets legalized across the country, do you foresee this country looking back at our time with the same sort of sense of shame that we look back upon the ’60s with?

JL: I think that day will come, and we will look back and we will laugh at ourselves. Will I be alive in 50 years? Probably not. But I think others will look back on it and say that we should be ashamed at ourselves. I think we will laugh at ourselves, the same way we laugh today and say oh, well that’s so silly to discriminate against people because of their race or color or nationality. Another generation will be saying, why did we do that? What was that all about, to put people down or to discriminate against someone because they are gay or lesbian?