OUR HEALTH, OUR FUTURE, OUR LONGMONT

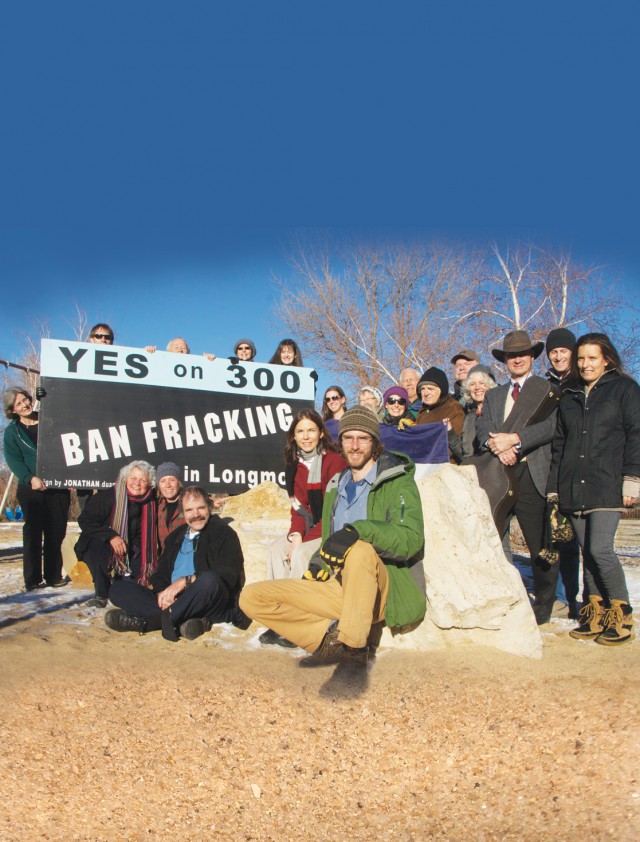

Michael Bellmont, the chief spokesperson for the group that succeeded in convincing a majority of Longmont voters to approve a ban on fracking in the city, is playing a harmonica under his cowboy hat. And he wants to go get his guitar before the photo shoot begins.

Bellmont is one of dozens of activists who have shown up to have their picture taken on a recent chilly December morning at a local snow-covered playground, in honor of being chosen as Boulder Weekly’s Person of the Year.

Or, in this case, People of the Year. After all, it was strength in numbers that made it possible for the group calling itself “Our Health, Our Future, Our Longmont” to overcome a $440,000 campaign launched by oil and gas companies in an effort to defeat the charter amendment banning hydraulic fracturing within city limits.

More than any other single group or individual, “Our Longmont” had a transformative effect on the discussion of perhaps the most important issue of the year facing Boulder County, hydraulic fracturing or fracking as it is commonly known. It is historically conservative, rural, Republican Longmont — not its liberal brother Boulder this time — that the county, state and even nation has to thank for its leadership on this important environmental issue.

After getting his guitar, Bellmont starts singing a tune he composed, which opens with the line, “We’ll have no friggin’ fracking in this town.”

He and the other volunteers who had the moxie to take on the energy industry and the pro-fracking governor of Colorado, John Hickenlooper, disperse reluctantly after the photo shoot, lingering to chat about the issues of the day and reflect on their accomplishments. Afterwards, the members of the Our Longmont steering committee gather at Bellmont’s Prospect neighborhood office, which they fondly refer to as “the war room,” a place they gathered often to strategize.

Question 300 campaign manager Kaye Fissinger says the roots of Our Longmont stretch back a year and a half to American Tradition Partnership (ATP), a right-wing group formerly represented by current Secretary of State Scott Gessler that sued the city of Longmont over its campaign disclosure requirements and helped bankroll what some called a “push poll” and smear tactics against a left-leaning city council member in 2009.

In a similar maneuver, ATP was conducting a telephone poll in the summer of 2011, Fissinger says, and among the questions was whether oil and gas drilling should be allowed on Longmont open space. It raised red flags for Fissinger, who at the time was serving as chair of the city’s Board of Environmental Affairs.

Not long after, TOP Operating made headlines for its plans to drill near Union Reservoir, a proposal that Fissinger and her board scrutinized closely. Local activist Padma Wick sent a Boulder Weekly article about fracking and the Union Reservoir plan to Sam Schabacker, Food & Water Watch’s mountain west director, who began mobilizing his organization’s resources. And Fissinger says she began alerting her network of contacts about the threat. Momentum began building with meetings featuring Phil Doe, environmental issues director for Be the Change, and Environmental Protection Agency whistleblower Wes Wilson. In November 2011, the Longmont City Council got an earful about the TOP plans during a public comment session.

In part due to the outcry, the company ended up signing a pact with the city in which it agreed to several operating conditions addressing environmental, health and safety concerns.

“We had to stop that train in its tracks, or we would be fracked already,” Fissinger says.

* * * *

Judith Blackburn, another member of the Our Longmont steering committee, says she originally heard about fracking from friends in New York, “and they said it’s going to happen in your part of Colorado, so stay alert.”

Committee member Jean Ditslear first spoke to city council about the issue in December 2011 after being inspired by anti-fracking testimony offered to municipal leaders from neighbor Chris Porzuczek, who lived next to a Union Reservoir parcel targeted for drilling.

Marilyn Belchinsky, another steering committee member, as well as musical spokesperson Bellmont, say they were inspired to get involved by another activist, Joe Bassman.

“When I learned about it, I felt angry that the corporations would have more power than the citizens of the city,” Belchinsky says.

It was Bassman who urged Bellmont to play one of his original anti-fracking songs at a community organizers’ meeting, saying, “Every movement has to have music!”

But the group, initially named Longmont ROAR (Responsible Oil and Gas Regulation) was splintered between those who thought the problem could be controlled through government regulation and those who believed only a voter-initiated ban was the solution. Blackburn says the coalition struggled a bit on decision-making and its governance structure, but it coalesced. Eventually, after extensive discussion and negotiation shepherded in part by Schabacker, the group gained consensus on the view that government officials could not be trusted to enact sufficient regulations and a citizen-driven ballot measure was needed.

Fissinger says that viewpoint was only reinforced when city council approved oil and gas regulations that were watered down in the face of the threat of a lawsuit from the Hickenlooper administration. And despite the watering down, she notes, the state is still suing the city over those regulations.

Clockwise from left, members of the Our Longmont steering committee include Marilyn Belchinsky, Michael Bellmont, Judith Blackburn, Jean Distlear and Kaye Fissinger, center | Photo by Susan France

Schabacker says the only reason city council narrowly approved those new rules was that they “saw that the citizens were leaving, and they could either get on the bus or be left in the dust.”

Similarly, the industry-funded Colorado Oil and Gas Association (COGA) is suing the city over the voter-approved ban, which appeared on the ballot as Question 300. But Our Longmont steering committee members are proud of their efforts and remain confident that the decision will stand up in court. They are putting together their own legal team to file as interveners in the case.

They attribute their successful effort to educate the citizens and get out the vote to hard work — and a quality reflected in the name of the street on which Bellmont’s office lies: Tenacity Drive. Fissinger notes that an early iteration of the grassroots group began meeting in the Longmont Public Library, which she says was a symbol of the research they were undertaking, then moved to the Longmont Safety and Justice Center, a name that speaks to the ultimate goal of protecting the health and future of local families. When the group moved to an office on Tenacity, she says, it was only fitting.

“There were a lot of heated discussions in this room,” Schabacker says.

When the focus of the group shifted from regulation to an outright ban, organizers filed for official nonprofit status under the new “Our Longmont” name, and one of the group’s biggest challenges was gathering 5,700 signatures within the six-week period required to get the measure on the ballot. More than 100 volunteers helped collect 8,200 signatures in the high heat of a fire-ravaged Colorado summer, an effort that Belchinsky contributed to — but she credits petition facilitator Joan Peck.

Indeed, it seems to have been a group effort. Ditslear, a graphic designer, was responsible for the printed materials and website. Belchinsky spearheaded much of the volunteer organizing with her people skills. Schabacker, among other things, brought the weight of the Food and Water Watch legal team, and the group keyed in on messages that would resonate with voters.

How did they overcome being outspent more than 17 to 1?

“We have a relationship with this community,” Bellmont says.

Belchinsky adds, “We had nothing to gain but our health and well-being.”

Ditslear notes that getting a knock or flier on your door from one of your neighbors is different than getting solicited by young workers who are unloaded into neighborhoods in vans and are paid by the oil and gas industry.

The committee estimates it distributed more than 12,000 pieces of literature, knocked on about 8,000 doors and made around 5,000 phone calls. The effort was David versus Goliath, considering the local activists were up against an industry-funded effort of full-page newspaper ads, television spots and glossy mailers featuring seven former Republican mayors who came out against the ban.

Belchinsky calls the latter “a joke,” adding, “That was history, and we were thinking of the future.”

No one seemed willing to claim responsibility for the catchy musical YouTube video spoofing the seven mayors’ ad campaign (http://bit.ly/7mayors).

And despite the group’s victory in November, the committee is not going overboard in celebrating the situation, especially given the fact that the city now has to shell out money to defend the voter-approved charter amendment against the COGA lawsuit.

“It’s a horrible position to be in,” Ditslear says, referring to the need to defend oneself against health threats and “to be told by your own state and governor you have no rights.”

Belchinsky says people from nearby cities volunteered as well.

“We knew that if we could succeed, other communities could stand a chance too,” she explains.

“There will be other communities that follow in Longmont’s footsteps in the next year or so,” Schabacker says. “The question is, where, and how many.”

Ultimately, Fissinger explains, the effort wasn’t about the activists involved.

She says, “it’s about our children, and grandchildren, and it’s a legacy we want to leave for them.”

2012 Person of the Year Runners-Up:

Brian Vicente, legal marijuana Respond: [email protected]