I had dreamed for years—decades—of seeing a baseball game in the Caribbean. In April of 2017, I spent three unforgettable days in Havana, Cuba, and have been kicking myself ever since for not splurging on a taxi ride to an Industriales game. In January of 2020, just before COVID-19 made virtually all travel impossible for a while, I skipped an opportunity to see a Caribbean World Series game during a trip to San Juan because my partner and I fell in love with the city and its beaches and didn’t want to spend any of our red-eye weekend in Puerto Rico seated in an old, decrepit baseball stadium.

But I absolutely adore old, decrepit baseball stadiums. A few months after my daughter was born, we were living in Portland, Maine, and I took a bus to Boston just to get a standing-room ticket to a Red Sox game and wander around Fenway Park’s historic nooks and crannies as the Sox and the Toronto Blue Jays battled. I also have a soft spot for the ugly hunk of concrete known as Oakland Coliseum, where for most of my 20s I arrived weekly via Bay Area Rapid Transit from my home in San Francisco for “Dollar Wednesdays”—tickets, hot dogs and sodas all just $1 each.

The Coliseum, built in 1966, is the last of the truly awful cookie-cutter baseball/football venues. It’s terribly designed for baseball and situated in an industrial no-man’s land with no restaurants or bars nearby. Imagine if the Broncos had left Denver for Las Vegas in the mid-1990’s and the Rockies had kept playing at the football-oriented original Mile High Stadium—that’s Oakland Coliseum. It attracts only hardcore Oakland Athletics fans interested solely in baseball, whereas Denver’s Coors Field, Pittsburgh’s PNC Park, San Francisco’s Oracle Park and other newfangled, idyllic, retro-minded stadiums attract not just baseball lovers but people who want a fun night out somewhere entertaining—indeed, a “park.”

Hiram Bithorn Stadium, south of historic Old San Juan, is the Oakland Coliseum of Puerto Rico. Built in 1962 and named for Hiram Gabriel Bithorn Sosa, a pitcher who was the first Puerto Rican to play in Major League Baseball—five years before Jackie Robinson debuted with the Brooklyn Dodgers as the first African-American MLB player—Hiram Bithorn is a beautiful old mess, with a strange, fanned roof and angled light towers that look like they’re about to tip over. It’s also got as much baseball history as any stadium still in existence, with the exceptions of Fenway (built in 1912) and Chicago’s Wrigley Field (built in 1914).

Born in a small seaside town called Carolina that bleeds into San Juan, Hall of Famer Roberto Clemente—drafted by the Brooklyn Dodgers and then scooped up by Pittsburgh after general manager Branch Rickey, who gave Jackie Robinson his legendary shot with Brooklyn, became the Pirates’ GM—played and coached for the Cangrejeros de Santurce at Hiram Bithorn in the MLB offseason until his tragic death in a New Year’s Eve plane crash in 1972. Clemente and Willie Mays once teamed up on the Cangrejeros to win both the Puerto Rican League title and the Caribbean World Series.

Growing up in Pittsburgh, I was picked on regularly as a kid for having dark Italian and Slovakian skin, often told to “go back to Puerto Rico.” Honestly, knowing Clemente had been Puerto Rican, I hated being bullied but thought the idea of someday going to Puerto Rico was pretty cool.

All of the Puerto Rican League (now called Liga de Roberto Clemente) teams play at Hiram Bithorn at some point in each winter-ball season, but it’s really the Cangrejeros’ home. Named for local workers (i.e., Crabbers) like the Steelers and Packers are, the Cangrejeros have won 16 league titles. The list of MLB Hall of Famers who have played for the Cangrejeros on their way to The Show, or in MLB’s offseason, is seemingly endless, ranging from Satchel Paige and Orlando Cepeda to Reggie Jackson, Jim Palmer, Frank Robinson, and Roberto Alomar.

Actually, Alomar and his brother—Sandy Jr.—both called Hiram Bithorn home while playing for the Cangrejeros. Born in nearby Ponce, Puerto Rico, Roberto Alomar spent 17 seasons in MLB and won two World Series playing second base for Toronto. These days, Alomar owns and operates the youth-oriented RA12, a Liga de Roberto Clemente team that bears his name and number.

When my partner, Mikayla, and I arrived at Hiram Bithorn on the last Wednesday of 2021 we checked out the Roberto Clemente statue and other memorials outside and then showed our tickets to see the Cangrejeros play the Mayaguez Indians to a team employee working one of the gates. He explained that, because COVID-19 had forced the rescheduling of some games earlier in the season, Roberto Alomar’s squad would be playing (against the Caguas Criollos) instead.

Having so much reverence for Cangrejeros history, I was disappointed to hear that RA12 would be the home team that night, but I was still very happy to see a Liga de Roberto Clemente game at Hiram Bithorn—2,700 miles from my home in Boulder in a city as remarkably gorgeous and welcoming as San Juan. Mikayla was just happy there would be beer and popcorn, and that this time we had a whole week in Puerto Rico, not just a weekend. (She hates sports but, for some reason, she loves me.)

As we were about to enter the stadium, Mikayla pushed up the sleeve of my shirt and pointed out the hometown Pittsburgh Pirates “P” on my left arm, telling the ticket taker how much I love baseball, and how much I love Clemente. The first major Latin American baseball star was not only a hero on the field (Clemente won two World Series, 12 Gold Gloves and an MVP award) but also gave his life when he insisted on personally delivering an overloaded airplane supplies to Nicaraguans affected by a December 1972 earthquake after the first two plane loads he sent were intercepted by a corrupt government on their arrival.

“I’ve got something to show you,” the stadium assistant told us after he saw my Pirates tattoo. He pulled up a picture of himself at the age of 11 with Roberto Clemente at Three Rivers Stadium in Pittsburgh on September 30, 1972–the day Clemente collected his 3,000th hit with a double in what turned out to be the last regular-season at-bat of his career.

In our—well, my—rush to get into the game, I told the guy how amazing his photo was but didn’t have a chance to ask him how he ended up seeing Clemente’s historic 3,000th hit in person. Our tickets (only $8 each) were general admission, so we sat down right behind home plate, surrounded by MLB scouts. With a capacity of 18,000 there were only a few hundred people at the RA12 game, as the Cangrejeros are the major ticket at Hiram Bitham, along with Caribbean World Series games and the odd regular-season Major League Baseball game (Rhianna, Billy Joel and many others have also performed there).

I had asked the man at the gate what players we’d be seeing, as Puerto Rican winter-ball games notoriously feature players signed by MLB teams who need extra offseason work on their way to the big leagues; MLB players who’ve had bad years and need to show off for scouts to get picked up by someone again; MLB stars just mingling back home for the winter; and grizzled Puerto Rican veterans just hanging on to a final shot at lacing up cleats somewhere, somehow.

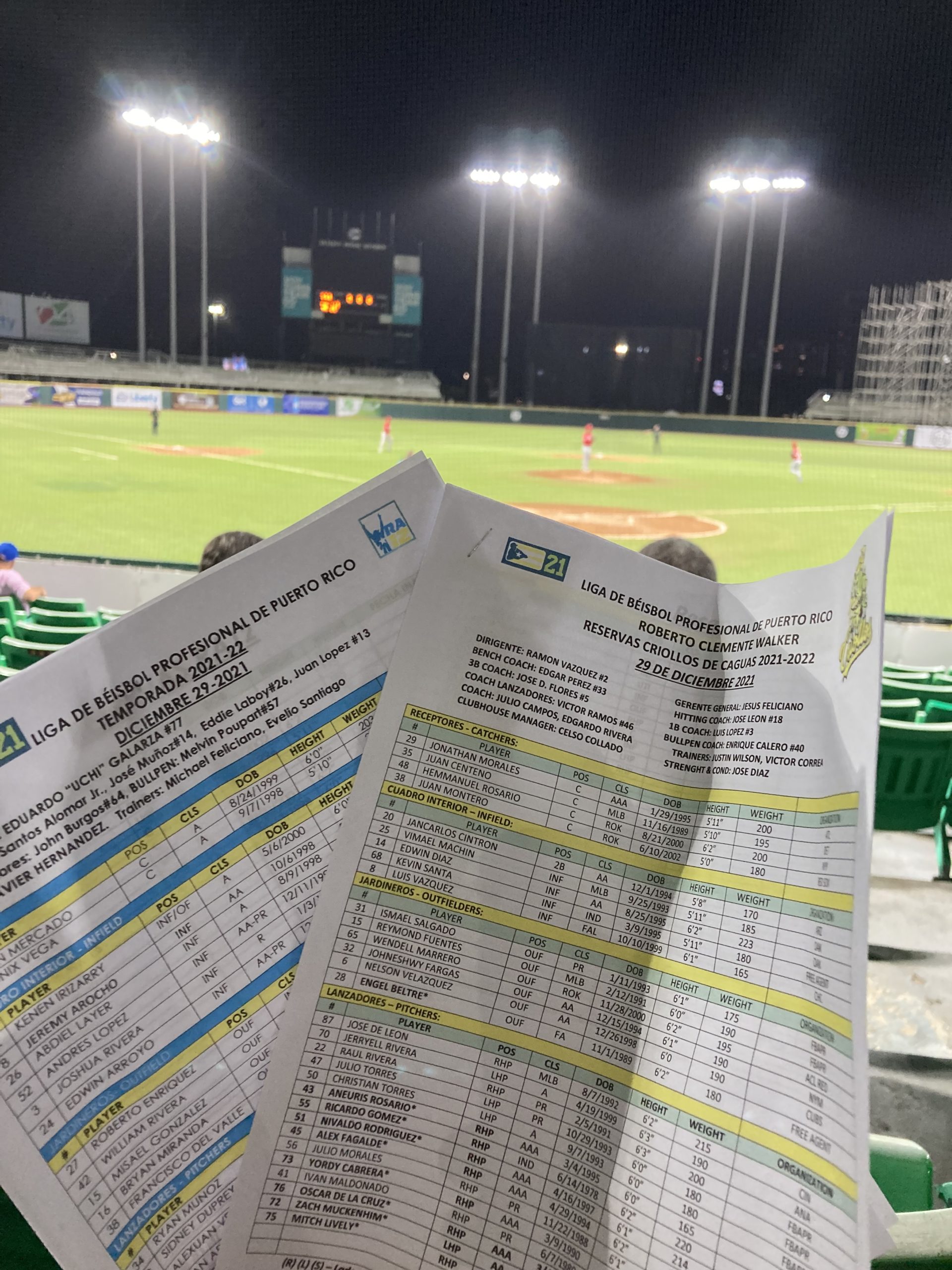

As I stood in line for refreshments, the guy from the gate walked up to me with the night’s roster sheets for both teams, saying, “You can’t have these but you can take pictures—and maybe you can get a picture with Roberto Alomar.” The sheets were very detailed, including each player’s personal information (birthdate, height, weight, etc.) and what MLB team—if any—owned their rights and to which level of pro baseball they were currently assigned.

I thanked him profusely and enjoyed looking at my photos of the two teams’ roster sheets for the game, noting that none other than Francisco Lindor (Puerto Rico native and All-Star with Cleveland, and now the Mets) was on the Criollos roster as a reserve. I also marveled at Roberto Alomar’s older brother—Sandy Jr., also a former MLB star—being listed as the coach.

Murals in the hallways leading to the sections behind home plate read “Boricua Power!” (bringing to mind the hilarious Ween song) with images of the retired Cangrejeros jerseys of legends such as Clemente and Orlando Cepeda. I was pumped.

The starting pitcher for RA12 was Ruben Ramirez, a 23-year-old Kansas City Royals farmhand who went to Point Park College in Pittsburgh after growing up in Puerto Rico. He’s hoping to make it to Major League Baseball. Ramirez’s parents were sitting right next to us, and the big right-hander’s father went to the dugout to massage his shoulders after a pretty brutal outing in which the Criollos knocked him around and his RA12 teammates played poor defense.

Midway through the second inning, the ticket-taker we’d met at the gate emerged again, having looked through the sparse crowd to find me. “You can have these,” he said, and handed me the roster sheets for both teams. I smiled and thanked him, astonished.

This was the sort of kindness I had only ever experienced in Cuba, where bartenders quickly and deeply befriend you to the point that they call their families and tell them to come down to their workplace and meet you.

The Criollos won the game 13-0, demoralizing RA12, but before the game ended Mikayla and I agreed on leaving early, because there was no cell service and our best bet to get back to our Airbnb in Old San Juan (seven miles north, around the Bay of San Juan) was to find a restaurant nearby with WiFi to snag an Uber or a phone to call a cab. It was well after 9 p.m. and there was almost nothing open within a mile of the stadium, so we were in for an adventure. Mikayla was a trooper just for sitting through that much of a baseball game with me on a Caribbean vacation.

Noticing us heading out, our buddy at the gate asked why we were leaving early. We explained that the game and the stadium were great, and that we’d enjoyed meeting him, but we had to leave to figure out a cab or Uber before the adjacent restaurants closed.

Suddenly, he told us he’d leave early, too, and offered us a ride to our spot on the north coast, a block above the infamous barrio of La Perla, featured in the music video for “Despacito.” He would not take “no” for an answer.

We reveled in witnessing a conversation between the guy—who finally told us his name was Felix—and his brother, also an employee at the stadium. Felix’s brother argued with him for a moment and then, as only siblings can do, rolled his eyes, threw his hands up and helped prepare a big, black SUV in the Hiram Bithorn parking lot for Felix’s generous ride.

Felix (a baseball lover and a manager of musicians) chatted us up on the way to our spot, about Cangrejeros history, about Puerto Rican baseball history, and—most importantly—about Clemente.

“He died helping people,” Felix beamed.

Felix ended up in Pittsburgh for Clemente’s final regular-season at-bat in Major League Baseball because Puerto Rico’s Little League had sent a group of its best players north on a field trip to see “The Great One”—Puerto Rico’s most famous athlete, maybe its most famous person—compete in the United States.

Discussing some of our favorite Caribbean baseball players, Felix and I bounced names off each other in the SUV until he mentioned Venezuelan pitcher Felix Hernandez, the Seattle Mariners star who retired last year.

“King Felix,” I said, and Mikayla chimed in that “King Felix” would be our nickname for our new friend.

Felix was surprised to learn that his 1972 visit to Three Rivers Stadium in Pittsburgh, where I lived until the age of 21, had taken place when Three Rivers, where I saw many games as a kid, was just a few years old. Clemente’s first decade-plus with the Pirates had found the Puerto Rican star playing his home games at tiny Forbes Field (on the campus of my alma mater, the University of Pittsburgh). Forbes was where young Clemente and his feisty Pirates beat the mighty big-city New York Yankees to capture the 1960 World Series.

Felix seemed even more surprised to learn that the stadium where he was photographed with Clemente just two months before the Hall of Fame rightfielder’s tragic death was long gone, replaced by riverside PNC Park in 2001.

“Wow,” he said.

Someday Hiram Bithorn will be demolished, too, but not my memories of an unforgettable trip.