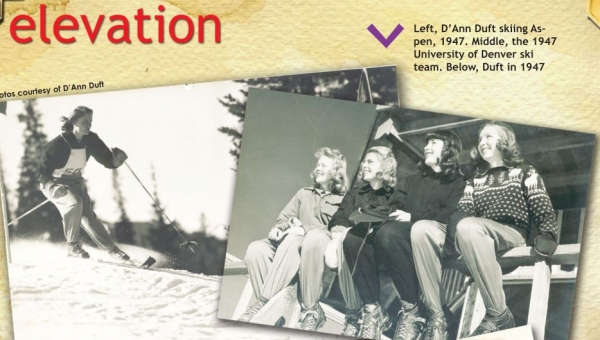

The technique is solid: weight firmly on the downhill ski, eyes ahead, shoulders square. There’s fire in the eyes, determination there. There’s also beauty and grace and something timeless. Skiing is, after all, a sport that’s been around for years, and the carved turn is a basic part of anyone’s repertoire, whether you’re a collegiate racer in 1947 or a World Cup athlete today.

The skier in the photo is D’ann Duft. The year is, indeed, 1947. And the place is Aspen. A Boulder native, Duft was one of four women on a powerhouse University of Denver ski team. The team also featured Barbara Kidder, Gerry Fleming and Louise Bulkley. Skiing in Colorado was still young then. Young enough for Duft to have a front row seat as Colorado’s white circus started to unfold. And the sport was also young — and small — enough that Duft would end up knowing personally many of the individuals who would shape the face of Colorado’s ski resort industry.

“It was an interesting time,” Duft says of the latter half of the 1940s. “The post-war period saw a boom in skiing. There was Max Derkum at Keystone and Larry Jump at A Basin.”

And there was the Bulkley family at Winter Park, the resort where Duft spent most of her time. One of Colorado’s most venerable ski areas, Winter Park has a rich history dating back to the 1930s.

The resort’s development started in 1937, with the construction of a ski jump and a few trails. By 1938, the first ski trains started taking skiers from the Denver area to Winter Park. It would take one more year for the first lifts to be installed, rudimentary surface tows that are a far cry from the detachable quad chairlifts the resort boasts today.

“We took the train up to Winter Park,” Duft recalls, “and we would stay up there for 50 cents a night.”

Lift tickets for that year cost a buck, and the money was plowed back into improvements, including clearing more trails and installing rope tows. By 1945, you could ski the upper mountain with rope-tow access, and by 1948, the mountain had reached the big time, with a total of three T-bar lifts and four rope tows. The majority of Winter Park’s development came under the guidance of George Cramner. Cramner, the manager of Denver’s Parks and Improvements in 1935, had a vision of a mountain city park that would become a winter sports Mecca comparable to European resorts. Duft, and her fellow teammates on the DU ski team ended up benefiting from Cramner’s work.

It was during this period that Winter Park became the de facto home of the University of Denver ski team, the place where Duft and other racers would hone their skills.

“DU started sponsoring a ski team,” says Duft. “This was before there was Title IX, but they still let the girls try out for the team. You’d try out and then you were on the team for good. They didn’t have any additional tryouts each year, you just got on the team and that was it.”

A self-taught skier, Duft ended up in fast company. Kidder, in particular, was a talented racer who would qualify for the Olympic team, but for the Olympic team, but opted out of competing due to pregnancy. Despite not becoming an Olympian, Kidder’s legacy is one of an athlete at the top of her game. Born to hall of fame skier Art Kidder Sr., Kidder had summitted many of Colorado’s 14ers by the time she was 11 years old. By 14, Kidder had qualified for the National Championships, held in Aspen in 1941. And in 1942, she represented Colorado in the Jeffers Cup Team Race in Sun Valley and raced to a Southern Rocky Mountain Ski Association championship. Other top finishes followed, including a first place in the downhill and slalom at the Intercollegiate Ski Championships at Winter Park in 1945. In 1946, Kidder would turn it up a notch, with a victory in the Snow Cup at Alta. Then came a second place in the Kate Smith Trophy Race, a victory in the Southern Rocky Mountain Ski Association Championships in Aspen, and a second in the National Championships. Her career has not gone unrecognized: Kidder was elected to the National Ski Hall of Fame in Ishpeming in the spring of 1977.

With Kidder leading the charge, Duft and the rest of the University of Denver ski team traveled across the Rocky Mountain region competing in the top events of the era, including the national championships in Alta and Aspen’s celebrated Roch Cup.

Named after André Roch, a Swiss skier, engineer and avalanche expert who helped develop the first ski run on Aspen mountain, the first Roch Cup was held in 1946, before any lifts existed and the athletes had to hike to the start of the course. The pioneering event saw a total of 23 athletes, 20 men and three women, race. A year later, when Aspen officially opened as a resort, the Roch Cup became the highlight of the season. Barbara Kidder would take the win for the women, with Dick Durrance and Steve Knowlton winning the men’s events.

“The dream came true for Aspen,” says Duft. “The ski races were a lot of fun. But there were a lot of injuries, too, because of the equipment. If your team got through a race without any injuries, that was good.

“We’d go up to Aspen for the weekend, and if you qualified then you’d race on Sunday. Afterwards they’d have a big dinner and about 8 p.m. you’d head back down to Denver. There was no tunnel and the drive would take six hours. You’d get home about 2 or 3 a.m., and then you’d go to class in the morning.”

Events like the Roch Cup were a far cry from the sophisticated course preparation that the ski racers enjoy today.

“You did a lot of your own packing,” says Duft. “Alta, that was an eye opener. … Those long wooden skis didn’t turn well in powder, and the snow was really deep. It was quite an experience racing there.”

Duft, now 86, has retired from skiing. “The last time I skied was when I was 70,” she admits. But to her credit, she wrapped up her career at Crested Butte, a mountain notorious for its challenging slopes.

Respond: [email protected]