You know things have gotten serious when Eric Henderson tells you not to ski.

And he’s not alone.

The former backcountry and heli-ski guide — more often known as “Hende” among those in the skiing world — joins a growing number of outdoor sports athletes and advocates in encouraging people to recreate close to home in order to flatten the curve of COVID-19 infections.

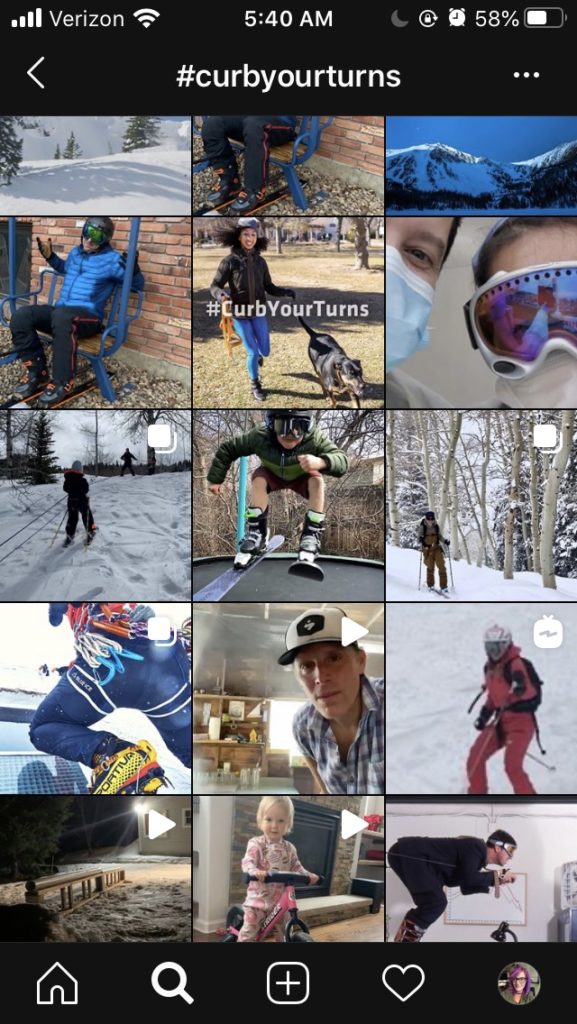

As a press representative for Snowsports Industries America (SIA), Henderson is encouraging skiers to hang up their helmets for the season to protect public health. Using the hashtag #CurbYourTurnsChallenge, SIA hopes to spread the message on social media as snowsports enthusiasts share photos and videos of themselves “skiing” in backyards and “boarding” melting piles of snow.

“SIA has taken a position where they are asking and hoping that people take this selfless act of curbing your turns or skiing at home and having fun with putting skis on in the backyard in the garden,” Henderson says. “Selflessness is very complicated in today’s word because honestly, we’ve never been asked, maybe with the exception of Vietnam, to do something for the greater good that’s not tangible. You can’t feel this.”

Courtesy of Eric Henderson

With tourists from all over the globe, ski resorts in Colorado became the hypocenter for COVID-19 infections, with the Denver Post reporting that 1 in 7 cases in Colorado have come from eight mountain counties with ski resorts. Acting swiftly on advice from Gov. Jared Polis, major ski resorts across the state closed on March 14 — but the trouble didn’t stop there.

“Across Colorado, the sudden shuttering of resorts has spurred a run on uphill ski equipment,” Jason Blevins reported in The Colorado Sun on March 21. “Forget toilet paper. The hottest commodity in Colorado high-country right now is alpine-touring skis.”

“Bentgate Mountaineering in Golden, and definitely shops on the Western Slope in, like, Cripple Creek, had astronomical days of sales of alpine touring gear,” Henderson confirms. “They sold out of bindings and boots in a couple of days.

“Then what happened is that the trailheads started to become crazy.”

Close to home, Loveland and Berthoud passes were inundated with folks looking to take advantage of the backcountry. Industry insiders such as Casey Day, a professional ski photographer and ski builder, and Tom Winter, a press representative for Freeride World Tour, both confirmed that conditions at both passes were congested in the days after major ski areas closed.

“Loveland Ski Area, as you know, is closed down, so we had a lot of people that were parking in the lower lots, all jumping in cars, driving to the top of Loveland where they could jump in or skin in and skiing down through the backcountry that way,” says Clear Creek County Undersheriff Bruce Snelling. “When it first came to our attention about two weekends ago, we worked with the Colorado Department of Transportation (CDOT), Colorado State Patrol (CSP) and Loveland Ski Area, and Loveland did a great job building some snow berms and cutting off some of the parking areas and restricting that access.”

The top of Loveland Pass on March 21, a week after ski resorts around the state closed.

Courtesy of Summit County Government

The following weekend, when there was still gathering at the passes, the Clear Creek County Sheriff’s Office worked with CDOT again to place more no parking signs along Highway 6 leading to Loveland Pass, and worked with CSP to monitor and tow cars when necessary.

“This weekend was remarkably different,” Snelling says. “We had a lot fewer cars, a lot fewer people. Before where we had 50, 60 vehicles parked, we were maybe down to 10.

“I get it that people want to get out there and recreate but really it’s not essential to drive from the metro area or other side of the mountain to Clear Creek and come to congregate and ski,” Snelling adds. “Our problem is, if somebody gets injured, that puts all first responders and our alpine rescue team at risk going into the backcountry.”

Henderson adds that it’s irresponsible to risk injury during a time when our health care system is expected to undergo strain as it deals with serious cases of COVID-19.

“Honestly, if you break it down, the biggest driver of this and the bigger underlying piece is taxing our hospitals, our rescue workers, and just the human code of skiing.

“You and I don’t know each other, but if you fell on backcountry terrain, you’d better believe I’d be helping you,” Henderson says. “That is inherently part of the code of backcountry skiing. And it puts people at risk [for contracting COVID-19] when we have to do that.”

Snelling says that Berthoud Pass is still a “problem area,” and that his office, along with CDOT and CSP, will be taking measures similar to those they took at Loveland Pass to mitigate congregation.

“We would really appreciate voluntary compliance as opposed to issuing a ticket,” Snelling says, adding that a ticket can cost up to $1,000 and one year in jail as a Class 1 misdemeanor for violation of a public health order.

But skiers aren’t the only athletes who are having to refrain from doing what they love. In mid-March, Slate reported that visitors began to swarm Moab, Utah, forcing local law enforcement to shut down campgrounds and hotels to visitors. Popular climbing spots in California and Washington were still hopping as of late March as well.

“Personally, it’s a little difficult because the situation is so dynamic,” admits professional climber Nina Williams. “Three weeks ago I thought climbing in the gym was going to be fine. Then two weeks ago all the gyms shut down and I came out and said at least the local climbing areas are open. But now we’re at a point where studies are starting to show that the disease can hang out on different surfaces for days, and the health care system is already so overburdened, so if you get hurt it’s just another burden on that.

“I have difficulty saying it right now because the climber in me is so sad and so badly wanting to get outside,” Williams says. “I don’t think people should be climbing outside for the greater good, for that consideration of others.”

“Realistically, no one should be climbing,” Jeremy Park, a member of the Washington Climbers Coalition’s board, told Slate in a March 20 story. Even Park admitted that he’d just come back from a climbing trip in Index, Washington.

“I started reading some articles and comments on local climbing groups about the small communities we impact, and the effect all this traffic has on them, and my opinion evolved,” he said.

Not everyone is abstaining, however, and Williams has noticed the shaming that has become commonplace in the weeks since social distancing was put into place, and she doesn’t think it’s productive.

“I think it’s useful to frame it in a way that turns it into an opportunity for ourselves,” she says. “Instead of pointing fingers and saying ‘you’ statements like, ‘You guys should be social distancing,’ turn it inwards and say, ‘What can I do for myself in these uncertain moments?’”

For Williams this has meant making time for things like meditation, running and even just sitting on the couch and eating cereal, “allowing myself to heal without any guilt.”

Williams has been plagued with guilt over not training as she normally would, and she suspects other athletes are feeling the same thing.

“I’ve had a lot of doubt about my decision to not climb outside because I have a lot of friends who are still climbing outside,” Williams says. “They aren’t posting about it [on social media] and I support their freedom, I support that choice. But then I look at my own choices and wonder am I being really lame by not climbing outside? But to me it’s not even a moral issue, it’s how can I be a leader in this situation and how can I tell people not to climb when I’m going outside?

“We have to give ourselves and people around us breaks because we’re all going to be handling it differently,” she says. “I want to be able to look back on this time five years from now and say, ‘I made that decision [to not climb] and I feel good about it.”