The race was about to start, and all Laura Knoblach could think about was the fact that the swim she was about to embark on was 48 miles long. Plus the reality that it was only .017% of the full distance she’d signed up to cover over the next 26 days.

There was also going to be the 2,237-mile bike ride. Then the 523-mile run to the finish.

It was going to be a challenging month, to say the least. But it was exactly the kind of thing Knoblach lives for.

Knoblach, a spunky and energetic 24-year-old University of Colorado grad, has a healthy, albeit masochistic, obsession with races that would make the average person weak in the knees. She’s been running since she was 9, she rides her bike everywhere, and grew up in Minnesota swimming in lakes when it wasn’t freezing cold.

This October, Knoblach traveled to Leon, Mexico, a city she’d never visited, to participate in a race only one woman had ever finished — a race equivalent to 20 combined Ironman triathlons known as the “Double Deca.” It would take her 26 days of near-non-stop action with minimal sleep. She would be tried, she would be tested, she would experience chemical skin burns and rescue kittens, and in the end she would smash the previous 1998 female world record by a full 10 hours.

But on the night of Oct. 4, just moments before the Double Deca Ultra Triathlon began at 10 p.m., it was the swim, the shortest portion of the race, that was daunting to her.

“You can’t really swim 48 miles in training,” Knoblach says. “So, I was really nervous. Like, what if I don’t make this swim? Then I came all the way down to Mexico for a month, to do nothing.”

Knoblach had been training for the race for a long time. Throughout the summer, she climbed 14ers, went on long runs through the mountains and even longer bike rides; she hiked, she swam, she pushed her endurance as far as she could, knowing that the race for which she was conditioning her body would push it much, much further.

So, with all that training and sponsors like Boco Gear, Deboer Wetsuits and Baretich Engineering behind her, she set those nerves aside. The race director began a countdown and when he got to “one,” Knoblach dove bravely into the Double Deca — the longest, most trying event she had ever dared.

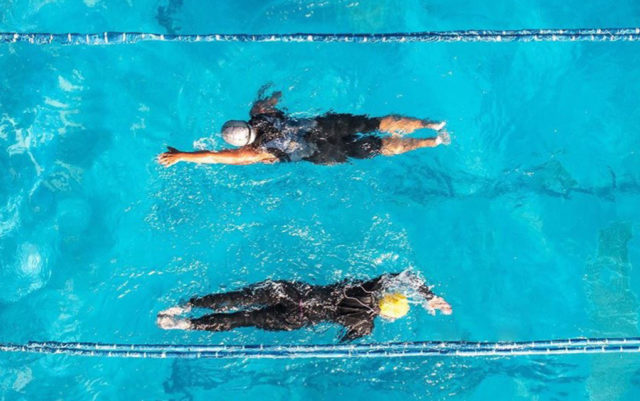

“The swim itself wasn’t actually that bad,” Knoblach says. What was bad were the chemicals in the pool. The race director, a veteran endurance racer, had asked the pool staff to turn the chemicals down, anticipating issues with athletes swimming in chlorinated water for dozens of hours.

Instead, the pool staff accidentally turned them up.

“Basically, any exposed skin got chemical burns on it and people were having respiratory issues,” Knoblach recalls.

Yet she swam though that discomfort, sleeping just over an hour between long sessions in the pool. When she finally stepped out of the water 53 hours later, covered in pink rashes that would last for weeks, it was with a sense of victory, followed by fatigue.

“I was just taken out after that, exhausted,” she says. Out of necessity, after her crew slathered ointments on her chemical burns, she slept for seven glorious hours.

“Then the bike was next,” she explains. The course was around Parque Metropolitano de León, a park with a big beautiful lake at the center ringed by a nearly four-mile bike circuit.

Which, to some, might sound monotonous, considering she was about to ride 2,237 miles. That’s over 500 laps, pedaling around that park like a hamster on a wheel.

“There’s positives and negatives about having a looped course because it is boring in some ways,” Knoblach admits. “But a positive aspect of it is you could be 300 miles ahead of someone in a race and be biking right next to them. So, if you pull energy from having other people around you, doing a multi-loop course can be really helpful.”

By that point Knoblach was getting to know her fellow racers well, and their camaraderie was building. Having friends to ride alongside fueled her, she says.

Still, despite those companions and the vitality they provided, and despite Knoblach’s undaunted attitude, her body was starting to feel the consequences of such an intense race.

“The first three days of the bike, I felt like trash,” she recalls. “I woke up and I was stiff, I was sore, my knee hurt and my ankle hurt. And I was thinking, ‘Oh, god, I’m two days in. How am I going to finish this?’”

But the laps kept passing, the miles ticked by and slowly her aches and pains muted. Every day after the third day on the bike was a better one, she says. She started going faster, doing more miles per day and gaining on the women’s world record set by Silvia Andonie 21 years earlier.

There was at least one memorable moment that broke up the monotony. About halfway through, she and another racer heard a cry from some nearby bushes. They saw a small kitten, alone, calling for help. At first, they assumed that it was just looking for its mother. But the next lap, they heard it again, in the same place. Maybe it was feral or rabid? They wondered, and again pedaled on.

“Third lap around, we see my friend Georgetta and she’s holding this tiny, tiny little white kitten just bawling her eyes out,” Knoblach recalls. And Georgetta was adamant: they needed to do something to help.

Problem was, they were on the complete opposite side of the lake as the race site, where they could pass the animal off to help. Nevertheless, the three racers took some time out and figured out how to carry the kitten on their bikes. It wasn’t easy, she says, but they did it, and they saved a life in the process.

“Georgetta is bringing the kitten home,” Knoblach says. And she’s named it DD for (you guessed it) Double Deca.

After 11 days in the saddle, when the bike portion was finally over Knoblach crashed and collected a few hours rest. Then she rose again and put on her running shoes.

Just like the bike, though, Knoblach says the first few days on the trail felt terrible. She wasn’t covering the distances she wanted.

“The first day of the run, I don’t think I even did a marathon,” Knoblach says shaking her head. “The second day, I did like 40 miles and it was just barely. The third day was another 40 miles, barely.”

Everything hurt and she felt awful. The third day of the run was the crux of the whole Double Deca, she says. That night, her unsinkable spirit was starting to feel heavy.

“I was pissed off. And I was just on the verge of tears because I wasn’t hitting enough miles each day to even finish.”

It was close to midnight. Her pace had slowed to a “gimpy, staggered walk” in her words, when the headlights appeared and a car rolled up alongside her. She knew it was someone with the race, so she waved, feigned a smile and continued walking, trying not to engage.

But someone jumped out of the car; it was Marcos, the race’s massage therapist, another friend of hers, and he could tell she was on the struggle bus.

“So, he starts giving me like a three-mile pep talk,” she says.

He was drilling it into her, “you’re going to be fine,” he said. “You’re going to get through this,” he reminded her.

That pep-talk actually worked, too, Knoblach admits. Her pace picked up, she pushed the pain to the back of her mind and the miles kept moving steadily past.

There were still nine days left at that point, and who-knows how many miles to go. But she called that moment the beginning of an “upswing.” And before she knew it, it was almost the last day of the race and she was almost done.

“I ran all night, maybe slept like an hour and a half, and then I ran all day and all night again,” she says. “I was just thinking, ‘Don’t blow this on the last day, Laura. You just gotta keep going.’”

Around 7 a.m. on Oct. 30 — 633 hours, 41 minutes and 39 seconds after the race had begun in the pool — she crossed the finish line a full 10 hours ahead of the previous women’s world record.

And on top of that, she had also beat the previous men’s U.S. national record by 44 hours, she says.

“That was a nice surprise,” she says.

For the next hour Knoblach sat on an air mattress, dazed and confused, holding a friend’s small dog and swaddled in a sleeping bag as people tried to get her to eat food and drink water. It was surreal, she says. Not unlike her return to the U.S.

“When you do a race that long, it’s so different from your normal life,” she says. “My house had become this little tent in this park in Mexico and it’s all I knew anymore. Coming back, I was like, wait, which one is the dream?”

Perhaps neither, and perhaps both. When she returned to the reality of life in Boulder, she was a world record holder, she had completed one of the longest most intense races in the world, and made her dream of doing so a reality — she was, in more sense than one, living the dream she’d chased through the desert.

Which she says, she’s still trying to wrap her mind around.