At the Boulder Transit Center on 14th Street, Tom Sampson loads his bike onto the rack of the N bus and fastens down the turquoise frame. Its sleek 4-and-a-half-inch rear suspension system and 29-inch wheels are designed for riding up steep technical terrain and navigating down-trail obstacles. A half an hour later, Sampson hops off at the Nederland Park-n-Ride, and within minutes he’s on one of the numerous trails that wind through the Magnolia area. When he finishes his ride, he’ll either have to circle back to the bus, or he can cruise Highway 119 or Magnolia Road down to Boulder.

“It’s pretty popular on the weekend — the trails are really good. The downfall is that you can’t ride [a trail] back to Boulder. Anyone up there on a bike would rather be on a trail,” he says, “That’d be the dream.”

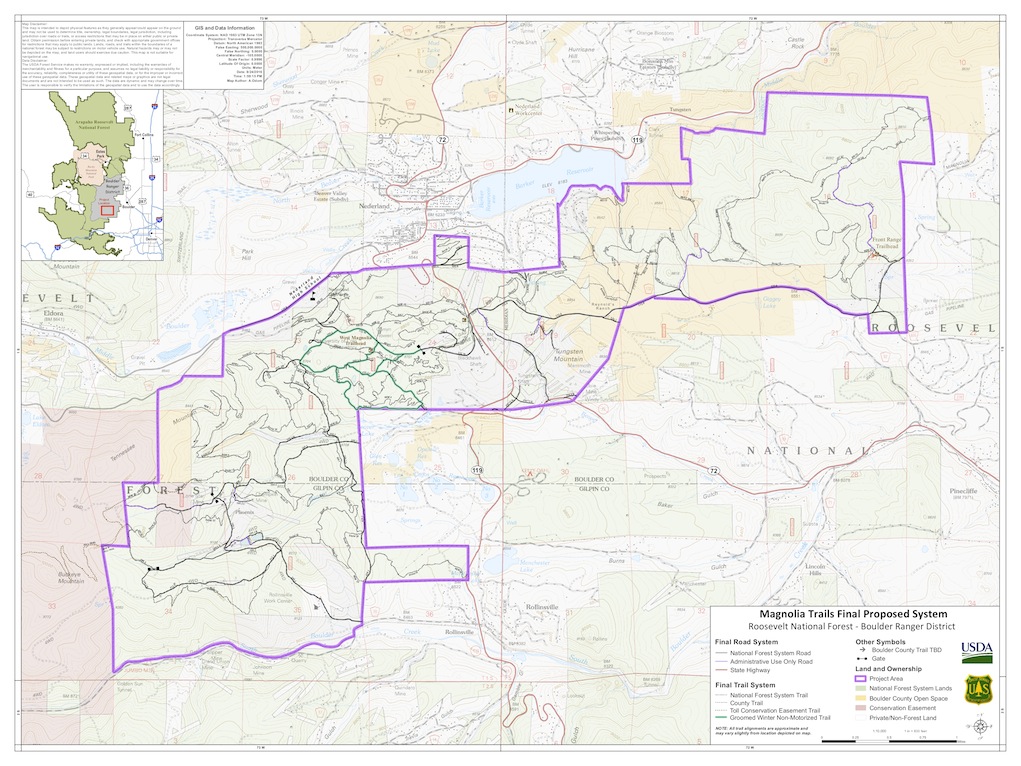

The Magnolia area of the Boulder Ranger District, which can be found generally south and west of Nederland and extending east towards Boulder (see map on page 20), has experienced “a substantial increase in recreation use” over the past several decades, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) Forest Service. An influx of people has created an estimated 62 miles of non-motorized trails, 46 of which are known to the Forest Service as “non-system” or “social trails,” the other mileage belonging to National Forest System trails.

These “unauthorized trails,” according to the Forest Service, have “led to resource damage, trail damage and unmanaged recreation use in the … area. As a result, the trail system has become unsustainable with environmental impacts increasing every year.”

“Basically, on a map it looks like a spaghetti-bowl of unsustainable trails,” said Recreation Manager Matt Henry with the Boulder Ranger District in an August press release.

“The goal is to turn that spaghetti bowl into a sustainable, non-motorized trail system that provides a better user experience that’s more in tune with what users are seeking,” Henry said. “We are hoping to do that by improving trail location, alignment and connectivity in a way that also minimizes the impacts to wildlife habitat.”

Balancing conservation with recreation has never been an easy job for those tasked with managing wilderness areas. To achieve this balance in the Magnolia area, the Forest Service has spent the last decade collaborating with several trail-user organizations on a plan to systematize and legitimize a new 44-mile trail system. The collaboration harkens to the Forest Service’s mission statement: “providing the greatest amount of good for the greatest amount of people in the long run.”

In August, the USDA officially released a proposal for the “Magnolia Non-Motorized Trails project,” which intends to fortify existing trails, build new trails and decommission or obliterate existing social trails that are redundant or conflict with environmental practices. After a period of public input and reconfiguration, the final draft is anticipated by the end of the year, and the first stages of implementation are scheduled to begin in 2017.

The project area involves 6,000 acres across the Boulder Ranger District of the Roosevelt National Forest in both Boulder and Gilpin counties. While the 44 miles of proposed trails will predominantly wind around National Forest System lands, some private and Boulder County lands will also be included in the project.

“I moved here because it’s a good area to be a cyclist. However, I wouldn’t say it’s a good area to be a mountain biker,” says Sampson, a professional cross country mountain bike racer who relocated to Boulder from New Hampshire in May. “[Trails are limited,] what you can access from town — all basic, beginner friendly, which is needed, but it’ll keep you entertained for a little while before you need something more.”

To find more without travelling too far, Sampson heads up to the Nederland area. “Trails up there are really nice, and super popular on the weekend when people can escape. As far as new trails go, I’m totally on board,” he says. “Having something new in the area would be a major step in the right direction.”

Steve Watts, director of the Boulder Mountainbike Alliance (BMA), has been working closely with the Forest Service and the Nederland Area Trails Organization (NATO) to ensure all voices are being heard. Eighteen months ago, Watts was appointed BMA’s first full-time executive director and has since deepened the group’s relationship with other organizations to improve trail experiences for all types of users, from hikers to horseback riders, bikers and skiers. His main concern with the Magnolia project is to ensure it reflects a balance between the Forest Service’s safety and environmental standards, the demands of a growing trail-using community and the integrity of the existing mountain bike community.

“We have allied ourselves with [NATO] and formed an ad-hoc committee with a few of our board members … to better work with the Forest Service in giving a voice to how the trail building and design get implemented. We’re very much in favor, and we’re excited to move forward in the implementation [stage],” he says.

The hope is that an effective trail system will provide a safer recreational experience for all visitors by reducing the likelihood of getting lost and clarifying interaction protocols between those walking on foot and those riding horses or bikes. Curating and legitimizing a trail and trailhead network can alleviate issues like the sedimentation of sensitive waterways and soil compaction and erosion that social trails and ad hoc parking areas impact over time. Systematizing the trails, the Forest Service states, “minimizes impacts to cultural values and sensitive wildlife habitat.”

Watts agrees wholeheartedly.

“We feel like a well-managed system that invites people to recreate in a legitimate way will discourage some of the behavior that has been present historically in the Magnolia area,” he says.

Watts hopes the proposed trail system will improve troublesome interactions between “locals, visitors and the transient population,” trash piles, gun or firework use, “people doing drugs or alcohol to excess” and other issues that have “really brought themselves to a head [in the Magnolia area] recently.”

“People have an opportunity in this Magnolia trails plan to change that in a positive way,” he says. “So we’re looking for a more defined way to use that unused land, replacing [these negative tendencies] with more positive behaviors and folks obeying the law.”

Michael Smith, “a longtime Nederland guy,” wildland firefighter and avid mountain biker, says, “I absolutely think that the better trail system — a well-managed system — will do nothing other than enhance the trails’ user experience. That’s also going to lead to a better economic model to the local communities, bringing more tourist dollars in and building that local community.”

Smith joined the NATO board of directors three years ago, and has lived in Nederland for more than 16 years. “Our primary concern [in negotiating with the Forest Service] has been to maintain the character and flavor of our trails, and also to become more inclusive for users within the Nederland area, making sure the trails are good for hiking, horses, cross-country skiing and fat biking,” he explains. “Every different [riding] area has a different feel that depends on how the local builders built their trails. Nederland has traditionally been a more technical riding area, and so we want to preserve that.”

He adds, “The real success in cooperating with BMA and the Forest Service has really been how to find our seat at the table.” As a small bunch of local riders, the group’s mission is to both sustain and improve the Nederland trails they’ve been riding for years.

“Overall, the cooperation with BMA and the Forest Service has been phenomenal,” Smith emphasizes. “It’s always difficult dealing with federal entities… and BMA has done well in hiring Steve [Watts] and others who are good at knowing the process and figuring out where we can get our voices heard. It’s been a long process to get everybody to sit at the table, and it’s a big deal that we’re all together now.”

Outdoor enthusiasts and professionals, like Sampson, are drawn from across the country to Boulder’s storied outdoor recreation, especially mountain biking. But upon moving to Boulder, Sampson says, “I was surprised to see how little mountain biking there was around the area, especially because around the country Boulder is known as a cycling hub. But it’s road cycling,” he realizes. “It’d be cool if it could be turned into an all-inclusive riding community.”

In recent years, Watts has noticed the influx of mountain bikers and riding popularity. “[We’ve seen] an unprecedented growth in population along the Front Range, all along 1-25 corridor. Mountain biking is a huge part of the demand from current residents and from those who are moving in. Younger people especially are coming with their mountain bikes.”

Watts’ vision for BMA’s future preserves this commitment to more accessible and responsibly built mountain bike trails. “We want to build quality systems, and also regional trails, connecting where we live to where we ride. So we can get out of our cars and onto our bikes and ride Boulder to Lyons, or Boulder to Nederland.

“[More trails are] much needed in terms of dispersing our use of mountain bike trails in sustainable and positive ways,” he says. “This is one piece of our puzzle.”