Throughout the prairies and foothills of Boulder County, there’s a plant causing concern and debate.

To the layperson’s eye, cheatgrass is barely distinguishable from the rest of the grasses surrounding it. But it’s been a thorn in the side of land managers across the West since the early 1900s.

Cheatgrass is a “significant component of foothills rangeland vegetation” along the Front Range, according to Colorado State University, and can contribute to wildfire risk, decrease plant diversity and impact pollinator and wildlife habitat.

Boulder County uses Rejuvra, a pre-emergent herbicide manufactured by Bayer, to help mitigate cheatgrass. Previously known as Esplanade, Rejuvra was approved by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in 2020 to be used on natural areas.

“We’ve been using Rejuva for several years, because we are so impressed with the results, and are confident that it is really the right way to manage our open spaces,” says Therese Glowacki, director of Boulder County Parks and Open Space.

But, months before the County re-evaluates its nearly 20-year-old weed management plan, some community members and scientists are voicing disagreement with the County’s use of the herbicide — especially the aerial spray method via helicopter — saying more research needs to be done to justify the use of Rejuvra on cheatgrass, a plant some say might not be worth worrying about on the Front Range at all.

Decades-old nuisance

Cheatgrass is found throughout the Front Range, but it’s not native.

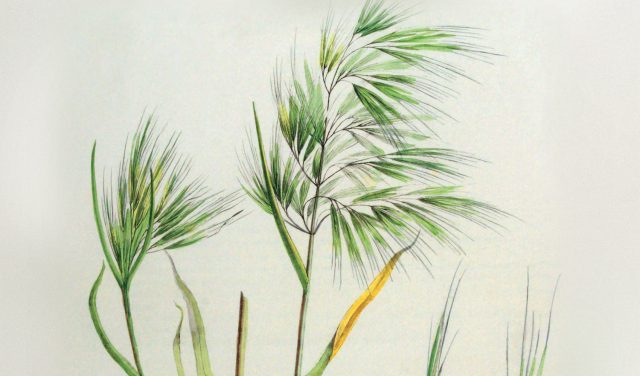

The opportunistic plant thrives in grasslands and disturbed ecosystems (like areas of construction, fire, floods or intense recreation) and can out-compete native species for nutrients, sunlight and water. It has dark green leaves with a hint of purple and small hairs speckled across the body of the plant, which can grow up to 30 inches tall.

Its seeds germinate in the fall and winter. By early spring, the annual plant (also known as downy brome) has already jumped ahead of its competitors — greening up while the rest are still waking from winter. It will turn brown and die at the beginning of summer.

Once it’s established, cheatgrass is hard to control — a single plant can produce thousands of seeds that can linger in the soil for five years before it germinates.

When it comes to fire risk, cheatgrass-filled ecosystems create problems. One Colorado State University fact sheet calls it “highly flammable,” where dense groups provide “fine-textured fuels that increase fire intensity and often decrease intervals between fires.”

“I’ve been on prescribed fires where there’s been cheatgrass … and it’s a problem,” says Stefan Reinold, resource management division manager at Boulder County Parks and Open Space.

According to the County, there have been about 210 overall applications of Rejuvra with the aim of controlling about 300 acres a year. Some projects are half-acre sites done by hand and others are aerial applications up to 500 acres. (They also use tractors for larger ground application). Rejuvra’s active ingredient is indaziflam, which is approved in the United States for use on hops, coffea, bushberries, tropical crops, stone fruit and tree nuts.

Rejuvra targets annual plants and stays in the top portion of the soil for up to four seasons, giving it the potential to remove cheatgrass for years after one application. In areas where the herbicide has been applied in the county, Glowacki says she sees less cheatgrass and more native plants.

The County has used other control methods like prescribed fire and grazing, but Glowacki says Rejuvra is more effective, costs less ($42 an acre), and requires less time and resources than other techniques.

“In the big scheme of things, if we could have an effective treatment that did not include any sort of herbicide, that would be our first choice,” Glowacki says.

Knowns and unknowns

Because Rejuvra is a relatively new herbicide, there are ongoing studies looking at its long-term effect on both plant and soil communities.

Carrie Havrilla is an assistant professor of rangeland ecology and management at Colorado State University. She’s researching how the herbicide impacts the whole ecosystem — something we don’t currently know.

“We have some evidence that indaziflam works pretty effectively controlling weeds and reducing weed cover,” she says. “But there’s less known about some of its more ecological and environmental impacts.”

Tim Seastedt, a professor at CU Boulder who studies prairie ecosystems and fire mitigation, says he is skeptical that Rejuvra doesn’t have extensive impacts on non-targeted communities like native annuals, soil microbes or invertebrates.

“It never hurts to have more information, but there seems to be a definite void in this one,” he says.

For example, if it stays in the soil for multiple years, he says there’s potential Rejuvra can move with erosion.

Glowacki acknowledged it would be nice to have more scientific research but is confident in studies the County has completed that show benefits from removing cheatgrass with Rejuvra.

“Intuitively, if you have good plant diversity on the surface, you are going to have good microbes, good carbon sequestration, better soil health, and more water-holding capacity as a result of removing cheatgrass,” she says.

Seastedt says cheatgrass isn’t the “enemy number one” that would justify herbicide treatment — arguing that competition from perennial grasses and available moisture makes cheatgrass less abundant and a decreased fire risk in the Front Range.

Brian Oliver, wildland fire division chief at the City of Boulder’s fire-rescue department, says cheatgrass is fairly easy to extinguish and “does not necessarily raise the fire risk” because it’s part of the overall fuel regime, but can pose a higher threat if it’s the predominant fuel carrying a fast-moving fire to heaver fuels.

Colorado categorizes cheatgrass as a “List C” noxious weed, meaning it does not require active management because of its high prevalence around the state, but counties are allowed to require treatment within their own jurisdictions.

“[List] C means you don’t bother [managing] it unless you see it as a particular problem, and so my interpretation is I don’t see it as a particular problem,” Seastedt says. “I’d walk right by and work on another issue.”

According to county-level distribution data from EDDMaps, cheatgrass has been reported 1,116 times in Boulder County, which is considerably higher than most other counties in Colorado (cheatgrass was reported 1,176 total times in the six counties surrounding Boulder). Patty York, a program manager in the State’s noxious weed program, told Boulder Weekly in an email that those numbers are likely higher across the state because reporting List C weeds is not a requirement.

Seastedt says applying Rejuvra in large patches, especially through aerial applications, is not worth it.

“Would I use the money to hire a helicopter to broadcast spray something that’s going to kill all seedlings for three years to get rid of cheatgrass? The answer is no,” he says.

Viable alternatives have been proven at a smaller scale.

Nick DiDomenico, co-founder at Drylands Agroecology Research (DAR), a regenerative landscape and agriculture nonprofit, had seven acres of hilly terrain on his farm that were overgrown with cheatgrass. Once he introduced strategic mob grazing by sheep in the early spring, it took two years for the hillside to revegetate with perennial grasses.

He says “strategic grazing is a really easy way to manage and mitigate” cheatgrass and that it is scalable, but faces limitations like fencing infrastructure, which can be expensive (Iowa State Extension found a 1,320-foot fence costs $1.48 per foot).

Public input

Residents in Boulder County have voiced concern for years about the use of herbicides on public lands. In response to public concerns, the City of Boulder stopped using glyphosate (Roundup) in 2011 — a policy change the County did not follow.

There’s currently a petition on MoveOn.org with 3,124 signatures calling for the County to stop using herbicide on open space.

There’s also been a renewed effort to question the County’s weed management plan after its latest aerial application of Rejuvra via helicopter on Nov. 1 at Hall Ranch, adjacent to the Town of Lyons.

Kathleen Sands, who helps organize the Lyons Climate Action Group, was at a town hall meeting the County hosted a few days before the Nov. 1 spray. She says people at the meeting were “up in arms.”

“We were just completely opposed to [the upcoming aerial spray],” she says, claiming the spray drifted to un-targeted areas.

According to Glowacki, the County has completed five total aerial applications of about 200 to 500 acres each. There were no opportunities for public input before the aerial Rejuvra program started because the County doesn’t require an engagement process to add or change herbicide application methods.

Havrilla says she understands concern over using Rejuvra, a relatively new herbicide “we don’t know a whole lot about,” but also notes the importance of managing cheatgrass.

“Boulder is faced with this huge challenge of a ton of this highly flammable and invasive weed on our open space,” she says. “And with [its connection to] the recent wildfires, biodiversity loss and impacts on soil health, we have to do something about those challenges and mitigate those risks.”

Earlier this year, Parks and Open Space and the Boulder County Commissioners paused aerial herbicide application as a result of public concern and to give an opportunity for the public to provide input on its weed management policy, which is slated to be re-evaluated this fall.

While that plan was last amended July 20, 2004, the State’s Noxious Weed Act requires counties to reevaluate weed management plans at least every three years, although changes don’t necessarily need to be made.

Glowacki says Parks and Open Space will still propose to have aerial applications as a method to help access remote areas, and because of its effective weed control and cost.

The County will make online and in-person opportunities for public input available on the Parks and Open Space website. The Boulder County Commissioners will make the final decision on the policy in the fall.